(RNS) — Since opening for business in Detroit on Labor Day weekend, Soul Tribes International has never been shy about being a purveyor of psilocybin, also known as magic mushrooms.

“Psychedelic mushrooms for sale,” its Instagram feed proclaimed on Sept. 12. “Join the Tribe.”

But Soul Tribes also portrayed itself as more than a place to score mushrooms. Based in the former Bushnell Congregational Church, a 60,000-square-foot red brick, white columned building built in 1939 in Detroit’s northwest side, Soul Tribes markets itself as a “spiritual organization” that utilizes “plant medicine, sound therapy, breath work, and ceremonial work.”

Psychedelics, the organization claims, are its sacrament, and those sacraments are for sale.

“They had billboards and then they had signs on the periphery of the church property saying ‘Shrooms: we deliver’ and a phone number,” Douglas Baker, chief of criminal enforcement at the city of Detroit’s law department, told Religion News Service.

Signs saying “Shrooms: we deliver” for Soul Tribes International line the property of Bushnell Congregational Church in Detroit. Image courtesy Google Maps

After a Detroit City Council member saw the advertisements and complained to police, an undercover officer attempted to purchase some of the mushrooms, according to Baker. The officer was allegedly told that proof of ID and $20 were all that was needed to be a member of Soul Tribes and make a purchase.

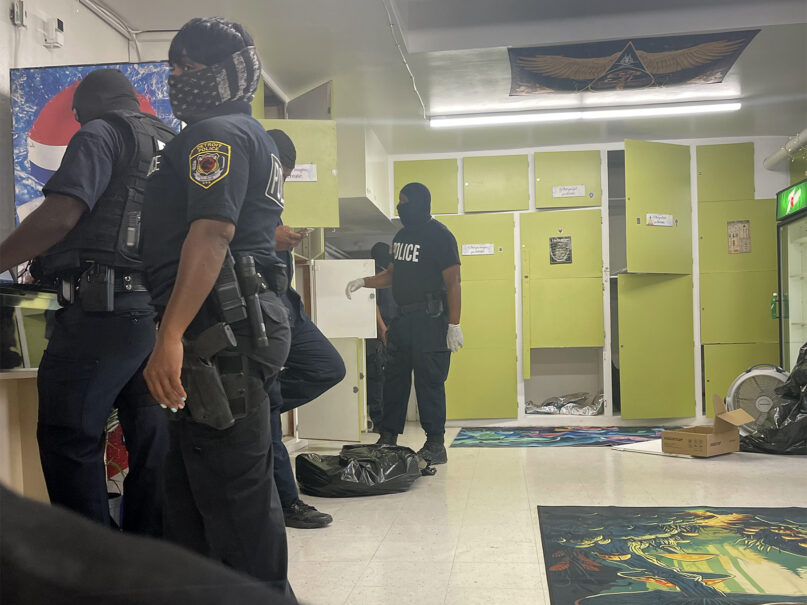

On Sept. 22, the police came back with a warrant and “found about 100 pounds of mushrooms and 125 pounds of marijuana on the property,” Baker said.

Robert Shumake, who goes by the name Shaman Shu, was shocked by the raid, which he said involved more than a dozen officers, none of whom were persuaded that they were violating Soul Tribes’ religious freedom.

“They just robbed us of our sacraments,” said Shu, who said the plants were “valued at over $700,000” and “intended for use in therapy sessions.” Besides citing his right to religious freedom, Shu believes the raid violated Proposal E, an ordinance Detroit voters passed in November 2021 intended to decriminalize psychedelics.

The Associated Press has reported that hundreds of churches in the U.S. use ayahuasca as a sacrament, turning to the psychedelic brew for healing. But Soul Tribes, experts say, is a test of just what makes psychedelics a sacrament, or a church a church? And what happens when the sacrament is up for sale?

Don Lattin, a journalist and the author of “God on Psychedelics: Tripping Across the Rubble of Old-time Religion,” said psychedelic churches are “all over the map” when it comes to their practices and beliefs. At Sacred Garden Church, in Oakland, California, profiled in Lattin’s book, congregants must attend eight community events and undergo a confirmation process and a health and safety screening before participating in the sacrament.

In addition, a board of elders and independent council ensure church leaders behave ethically and those who oversee psychedelic ceremonies participate in rigorous training. The church does not sell sacraments.

“They’re very cautious. They’re not just a dispensary,” said Lattin. “I differentiate that kind of a church to one that’s basically you show up, you instantly join, and you’re instantly buying mushrooms.”

In an email, Shu said members are required to “declare their spiritual belief,” view a video on the freedom of religion and pay $20 a month to become members. Shu also emphasized Soul Tribes is a ministry with sincere beliefs about the power of plant medicine. “We haven’t profited anything. This is my life work. I haven’t made one dime.”

Robert Shumake goes by Shaman Shu. Courtesy photo

Shu said he has been appointed as a leader in the Maasai tribe of eastern Africa, and that Soul Tribes is affiliated with the Oratory of Mystical Sacraments, a religious organization that has a network of members “successfully exercising their right to religious freedom” through the use of psychedelic sacraments, according to its website.

Shu and other Soul Tribes affiliates have not been charged with any crimes. Instead, the city of Detroit filed a nuisance action calling Soul Tribes a “distribution center for unlawful controlled substances” that is “masquerading as a church.”

On Wednesday (Oct. 11), Wayne County Circuit Court Judge Patricia Fresard authorized a temporary restraining order preventing Soul Tribes from operating as the parties await a hearing on the nuisance action.

Shu, who was raised in a Christian family, told RNS he had his first experience with sacred plant medicine in Costa Rica in April 2021, an event he called “transformative.” The experience allowed Shu to face trauma from his experience with homelessness, sexual abuse and the death of his 8-year-old brother. When he returned home to Detroit, Shu felt “reborn,” he said, a feeling he wanted others to share. He soon became involved in efforts to pass the Proposal E ballot measure, which passed with 61% of the vote in November 2021.

Proposal E states, “The enforcement of any laws imposing criminal or civil penalties for the personal possession and therapeutic use of entheogenic plants by adults shall be the lowest law enforcement priority in the City of Detroit.”

But while the ordinance is intended to decriminalize the “therapeutic use of entheogenic plants” to the “greatest extent possible,” it does not explicitly permit the sale of psychedelics, nor does it technically legalize the use or distribution of the substances. In an email to RNS, Shu said that the proposal does allow the sale of psychedelics because it includes the “use or provision” of psychedelics “with remuneration” in its definition of therapeutic use.

“The city cannot decriminalize something that’s criminalized by the state,” said Baker.

RELATED: In ‘God on Psychedelics,’ Don Lattin offers a roadmap of congregational tripping

Soon after Proposal E passed, Shu said, he felt called to purchase a church, and in March 2023, Soul Tribes International Ministries purchased the Bushnell Church property for $80,000, according to the city’s complaint.

Shu planned for Soul Tribes to host ayahuasca and psilocybin healing ceremonies at the property and to build a retreat center for breath work, meditation and yoga. Promoting interaction with the divine, entheogenic plants help people heal from mental health challenges, Shu said, and could be especially beneficial to underserved communities in Detroit.

In the meantime, Soul Tribes opened its sacrament center at the church in early September, selling products made from psilocybin mushrooms grown by Shu. The organization has been holding psychedelic healing ceremonies free of charge at another location as the church is renovated.

Psilocybe mexicana mushrooms in Veracruz, Mexico, on July 2, 2019. Photo by Alan Rockefeller/Wikipedia/Creative Commons

It also operates a website, shroomsdetroit.com (which is separate from group’s official website), advertising its sales of microdose chocolate bars, Wakanda Blue Mushroom gummies and Penis Envy Magic Mushrooms, for $50 to $100.

The transparency is apparently what did the organization in. In addition to the billboards, on Sept. 16, a week before the police raid, Shu emailed Detroit police Sgt. Crystal Johns to inform the police department that Soul Tribes was a legally registered religious organization dedicated to “supporting Indigenous people and practicing our sacred sacrament.”

“I’m just in total shock to go through every step to do it legally and aboveboard, and then for the church to be raided,” said Shu.

Ayize Jama-Everett, a therapist who heads A Table of Our Own, a conference for Black professionals in the field of plant medicine, said that when it comes to psychedelic churches, “the question is: How do you gauge sincerity?”

Jama-Everett pointed to Zide Door Church, also in Oakland, led by founder Dave Hodges. Raided by police in 2020, it has since reportedly gained 70,000 new members who pay $5 a month and make a donation for sacramental psilocybin and cannabis.

“With Dave Hodges and Zide Door, I believe that Dave believes that he is engaging in sincere religious use,” Jama-Everett told RNS. “But I do not believe that anybody else attending that church has sincere religious beliefs. … And I actually think that hurts the religious use argument.”

Attorney Allison Hoots is president of Sacred Plant Alliance, an association of churches dedicated to “sincere, safe, and ethical ceremonial use of plant medicine sacraments.” The alliance’s member churches hold one another accountable to ethical standards and encourage church participants to report any adverse events. Each church is required to agree to a set of guidelines, including holding health screenings for participants, only using the sacrament for religious purposes and having emergency protocols in place.

Hoots said psychedelic churches will be held to a different standard than other religious groups due to the specter of the war on drugs. But she acknowledged that accountability mechanisms such as those provided by Sacred Plant Alliance are important due to the potential for harm.

“There are risks. There aren’t inherent harms, but there are inherent risks with any substance. And the impact of these sacraments are massive,” said Hoots. “I think it needs to be taken seriously, and handled with reverence and responsibility.”

RELATED: Psychedelic churches in US pushing boundaries of religion

This story has been updated to reflect Shaman Shu’s statement on Proposal E.