(RNS) — America’s congregations are in trouble these days.

They’ve faced polarization, a worldwide pandemic, shrinking memberships, a changing culture and uncertain futures.

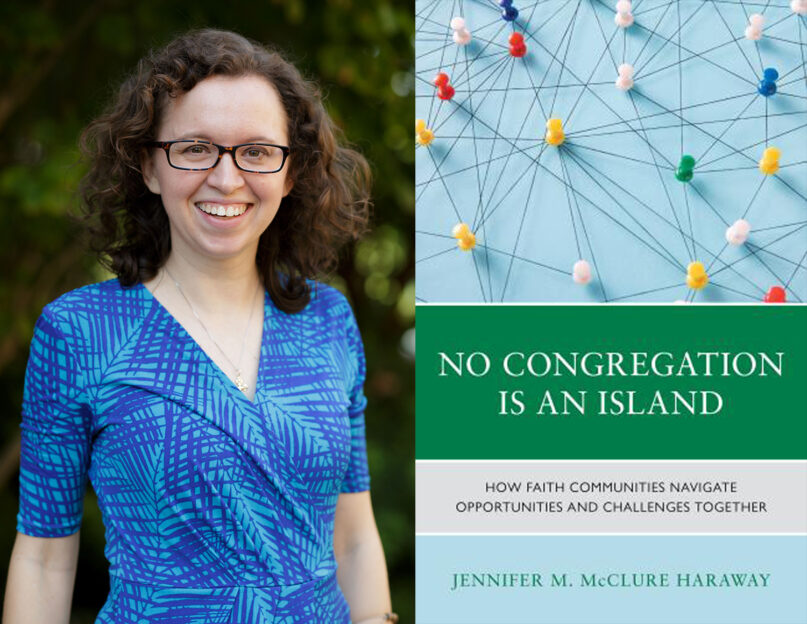

Like most of us, they could use a few friends to face their troubles with and figure out together how best to respond, says Samford University sociologist Jennifer McClure Haraway.

“Congregations are experiencing a lot of change in opportunities and challenges,” Haraway said. “We navigate those more effectively when we work together. When we feel like we’re alone, we tend not to navigate them as well.”

In her new book “No Congregation Is an Island,” Haraway hopes to remind churches and other houses of worship of the benefits of working together. The book is based on a survey of more than 400 congregations in and around Birmingham, Alabama, about how they partner with other congregations.

After finishing her initial studies in 2017 and 2018, Haraway wrote a series of academic papers about her findings. But, she said, no one aside from her fellow scholars read the studies.

“Those articles are very technical — and I can’t hand them to any local minister, even though they have practical applications,” she said.

That led to turning her findings into a short and helpful book that would be accessible to congregational leaders. Based on her initial findings along with follow-up interviews and stories, the book looks at how congregations work together with folks from their own tradition as well as those from other groups — and gives tips on how to better collaborate.

One of her tips: Go to denominational meetings, which still matter even during a time when those denominations are in decline. But go for the friendship, not necessarily the programs or debates.

“One of the most important things these events can and should nurture are the relationships between ministers and leaders,” she writes.

While working in their own tradition is simpler — having shared theology and common practices makes trust easier — ministers shouldn’t limit themselves to only cooperating with folks from the same denomination, Haraway says. Otherwise, they might miss out on the insights that come from people who have a different point of view.

Working across traditions can be complicated, Haraway writes, especially if groups have different views on core doctrines. Still, as the leader of one non-denominational church put it, there’s a benefit in breaking free of groupthink.

“Sometimes I just want to talk with my mom’s Methodist pastor and see what they’re talking about, because I think they’re probably having a different conversation,” Haraway recalls him saying. “That would be helpful for me.”

The 438 congregations in the study include houses of worship from eight counties, all in the middle part of Alabama. Most are Christian, given Alabama’s place in the Bible belt, but the study did include mosques and synagogues. The congregations ranged from churches with a handful of members to megachurches.

Despite their differences, the congregations in the study often had a great deal in common. One chapter of the book compares the Churches of Christ, a group that uses no instruments in worship, with the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. The two groups are different from the outside: the Churches of Christ are fiercely independent and skeptical of any hierarchical structures, while the Latter-day Saints have a highly organized and interdependent structure with clear leaders at the top. Both have their own distinct theology.

Yet, both are so-called restorationist movements — founded by people trying to capture something essential about Christianity they believed was lost. Both have a clear sense of their mission and an identity tied to that mission.

“That makes them very tight-knit,” Haraway said.

One of the last chapters of the book deals with groups that cooperate across racial lines. Almost half the groups Haraway studied had no ties to congregations that had a different racial makeup. That did not surprise her, given the country’s continuing racial divides and the way churches often closely associate with other congregations from their own denominations — and those denominations are divided racially.

Pastors from different predominantly white groups are much more likely to have full-time roles, while many Black and Hispanic pastors are bi-vocational, having a day job alongside their ministry. That can make difficult even something as simple as setting a time for pastors from different backgrounds to meet.

The book offers no easy solutions but does offer some advice from congregations that have been able to work together in diverse settings.

“To build healthy partnerships across race, know that it takes time to develop trust,” she advises. “Be patient and be willing to do what it takes.”

Haraway said congregations get three different kinds of help from each other: emotional support, informational support and what she called “instrumental” support. Sometimes they need ideas or a partner who can collaborate on projects. And sometimes a bit of emotional support — especially for pastors — is crucial, she said.

“One of the ministers I talked with said that he was recently talking with another local pastor who said, ‘You know, some days I just want to quit,’” she said. “And that other pastor said, ‘Me too. Let’s go get lunch.’”