(RNS) — “U.S. military hired terror-tied chaplains,” the title of the TV segment blared in all caps.

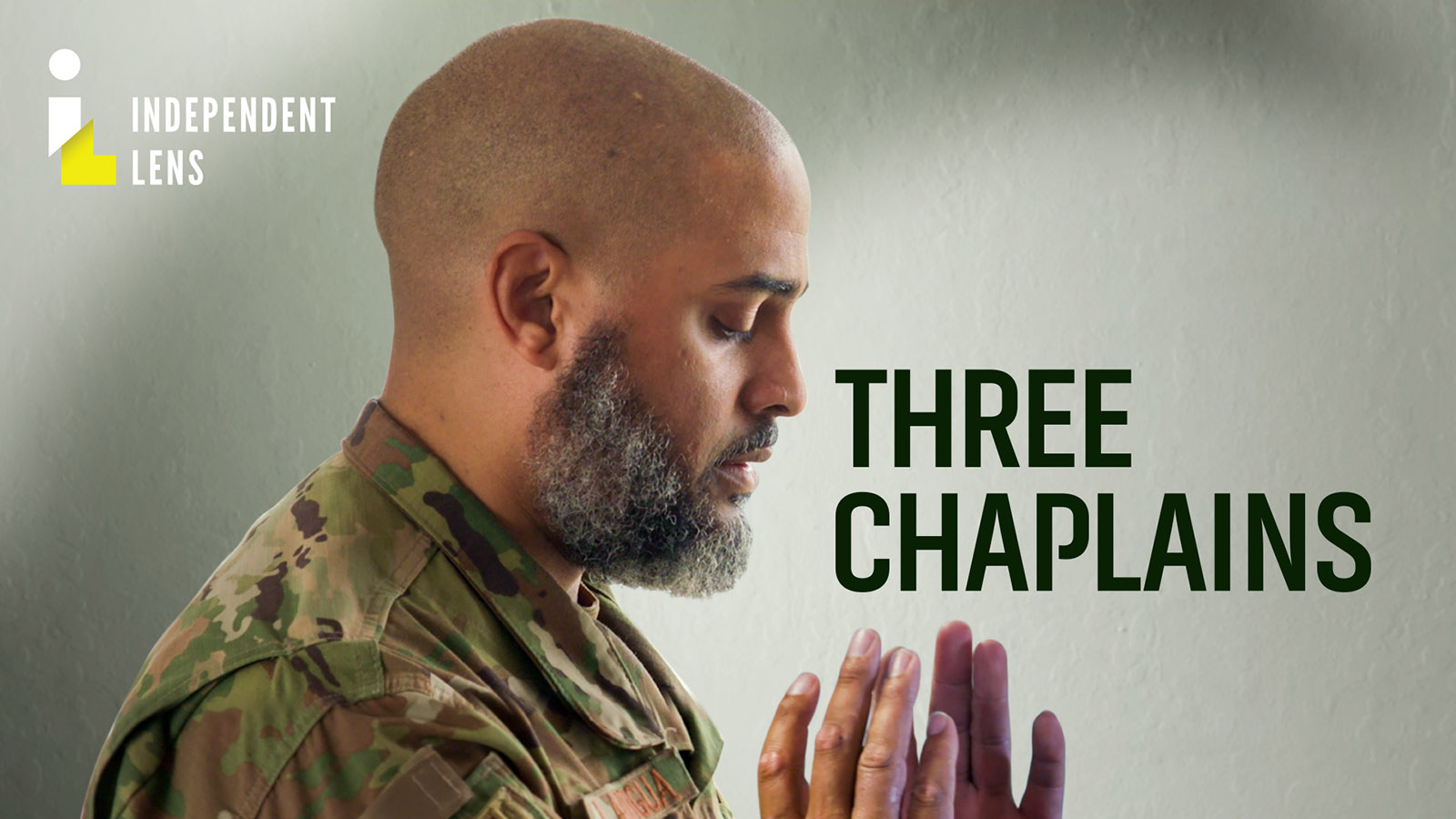

An image of chaplain Rafael Lantigua in military fatigues flashed across the screen. “Who needs to infiltrate the military now?” “Fox & Friends” host Steve Doocy asked. “Have the military hire you.”

“No mention of my military history, no mention of my service, no mention of my background,” Lantigua said about the 2014 national news broadcast in the new documentary, “Three Chaplains.” “Just an accusation, my face and my name.”

When Lantigua joined the military in 1994, he knew the choice could come with risk. As a biracial Muslim man, he has often been perceived as the “other,” and even in his faith community his career choices were subject to scrutiny. But nearly two decades later, he’s a major in the Air Force who has impacted scores of service members because of, not despite, his faith.

Poster for the documentary “Three Chaplains.” (Courtesy image)

Filmed during former President Trump’s so-called Muslim Ban, the COVID pandemic and the U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan, “Three Chaplains,” a new documentary from Terrace Films and Independent Television Services, gives a rare look behind the scenes of the U.S. military. Though dotted with moments of pain — the anguish of the Black Lives Matter protests, the horror in the wake of the shootings at two New Zealand mosques — the film’s message is one of resounding hope. Amid global and personal crises, faith, the film suggests, can be an indomitable source of resilience, unity and optimism.

Given the ongoing Israel-Hamas war, that message, the filmmakers told RNS, couldn’t be more timely.

“Although it’s not explicit in the film, this is an interfaith collaboration,” director David Washburn, who comes from a Jewish background, said about working with his co-producer, Razi Jafri, who is Muslim. “We come from very different backgrounds, different faith traditions, different levels of engagement with our faith. But I think what we’re trying to do is show and model for others that you can come from these different backgrounds, and especially during intense times, it’s imperative that we double down and try to see each other’s perspectives, and move forward.”

Lantigua told RNS he believes the documentary can encourage viewers to rise above anger and bigotry. “I think this film, in light or in the face of this conflict, should remind individuals of our humanity,” he told RNS in a call from where he is currently stationed in Anchorage, Alaska.

Khallid Shabazz hugs a soldier at Joint Base Lewis-McChord near Tacoma, Washington. (Photo by David Washburn)

Washburn originally developed the idea for the film in 2015 as he was creating a short film series on Muslim veterans. After being introduced to Muslim military chaplains, he was struck by the rich intersections they inhabited. The notion of Muslims, who have long been demonized in American media and politics, being in positions of spiritual leadership in the often-glorified U.S. military was provocative.

Washburn’s project was ambitious. To be faithful to his subjects, he wanted to create a documentary spanning several years and straddling several states, from Boston to Texas to Alaska. His vision persuaded funders at the Doris Duke Foundation to join the project.

In 2016, Washburn began filming at Joint Base San Antonio-Lackland, in Texas, where Lantigua was serving as chaplain. Washburn was surprised to capture the conversion of a young, white trainee who had decided to become a Muslim. Surrounded by his peers, the cadet repeated after Lantigua, reciting the Shahada.

Rafael Lantigua at the US Air Force Academy near Colorado Springs, Colorado. (Photo by David Washburn)

“It’s one of those moments when you’re filming and you know this is going to be in the film,” Washburn told RNS, “because it is the very essence of religious freedom that I think all Americans cherish and believe in, but here it’s happening inside the military.” Washburn expected the scene to create dissonance for some viewers, but meeting misconceptions with new stories, he said, is what expands people’s imaginations.

By tracking the chaplains long term, Washburn’s film gives viewers a taste of the distances the service members traversed and of how their careers evolved over time. In less than an hour, the film charts Lantigua’s rise to major, chaplain Khallid Shabazz’s ascent to colonel and chaplain Saleha Jabeen’s journey from chaplain candidate to the Department of Defense’s first female Muslim chaplain. For Jabeen, watching her story unfold on film was humbling.

“When you are in the day-to-day grind, you tend to forget,” said Jabeen. “But when you have a zoomed-out point of view, you go, wait. I am actually taking care of people, changing history, and I’m a part of this? I took a moment to be like, thank you God because I know I don’t deserve this.”

In addition to highlighting the chaplains’ achievements, the filmmakers also wanted to be transparent about the discord often inherent to being a Muslim chaplain. Given America’s recent military history — the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, the reports of torture of Iraqi prisoners at Abu Ghraib — there are plenty of Muslims who question why one of their own would opt for a career in the U.S. military.

In one pivotal scene, Jabeen speaks with Shareda Hosein, a Muslim chaplain who served in the military for 35 years and was barred from becoming the first female Muslim military chaplain in the early aughts.

Hosein tells Jabeen that after seeing many horrible actions taken by military personnel, she wouldn’t join the military today.

Saleha Jabeen takes the oath to enter the Air Force chaplain corps, at Catholic Theological Union in Chicago. (Photo by David Washburn)

“That scene to me articulates the tensions within the Muslim American community about not just Muslims in the military, but Muslims in the government,” Jafri, one of the producers on the film, told RNS. “There’s a lot of people in the Muslim American community who disagree with the involvement in Iraq and Afghanistan. Shareda is sharing that perspective, which I think is a very authentic and real perspective for many, if not most, American Muslims.”

When asked about the conversation, Jabeen told RNS it wasn’t the first time she’d heard such concerns. But she views her faith as fully compatible with a career in the U.S. military.

“I knew I had to join the military,” said Jabeen. “If that meant taking on this journey where people don’t know anything about my religion, my spirituality, then I’ll teach them. Because I know everybody is hurting, and I have something that can help people have hope.”

Jabeen told RNS she knew she would face an “uphill battle” no matter what career she pursued. “I’ll choose this one, because that way at least I’ll enjoy wearing my fatigues and having a cool military life,” she laughed.

The documentary will premiere Monday evening, Nov. 6, as part of the Independent Lens documentary series on PBS. After that, it will be available to stream for free on the PBS YouTube channel and PBS App.