(RNS) — In a Hollywood era dominated by spandex and CGI, Godzilla has largely become just another big-budget monster, a Transformer in snakeskin. It wasn’t always that way: The original Godzilla was a more complex character who reflected postwar Japan’s fears about nuclear weapons. With the franchise turning 70 next year, Toho Studios, creator of the very first Godzilla movie, brings the lizard god to its roots as the star of a startling and scary parable about the shame of war.

“Godzilla Minus One,” opening in the U.S. on Friday (Dec. 1), begins as World War II is ending. A fighter pilot, played by Ryunosuke Kamiki, is hiding out at a repair base in the Pacific, deeply ashamed after claiming his plane has mechanical problems to avoid joining a kamikaze mission. When a dinosaur-sized Godzilla rises out of the ocean, he gets his chance at redemption, only to get knocked out in his attempt. He wakes to find Godzilla gone and everyone else at the base dead except the lead mechanic, who vilifies him for his cowardice.

The pilot returns to Tokyo to find it in ruins, his parents dead and his one surviving neighbor disgusted that he chose to live rather than fulfill his kamikaze mission. Years pass in which he tries to build a life with Oishi, a woman who survived the firebombing of Tokyo, along with the orphan girl she saved. But haunted by the shame he still feels, he finds himself unable to commit to them. “My war is not yet over,” he confesses to Oishi.

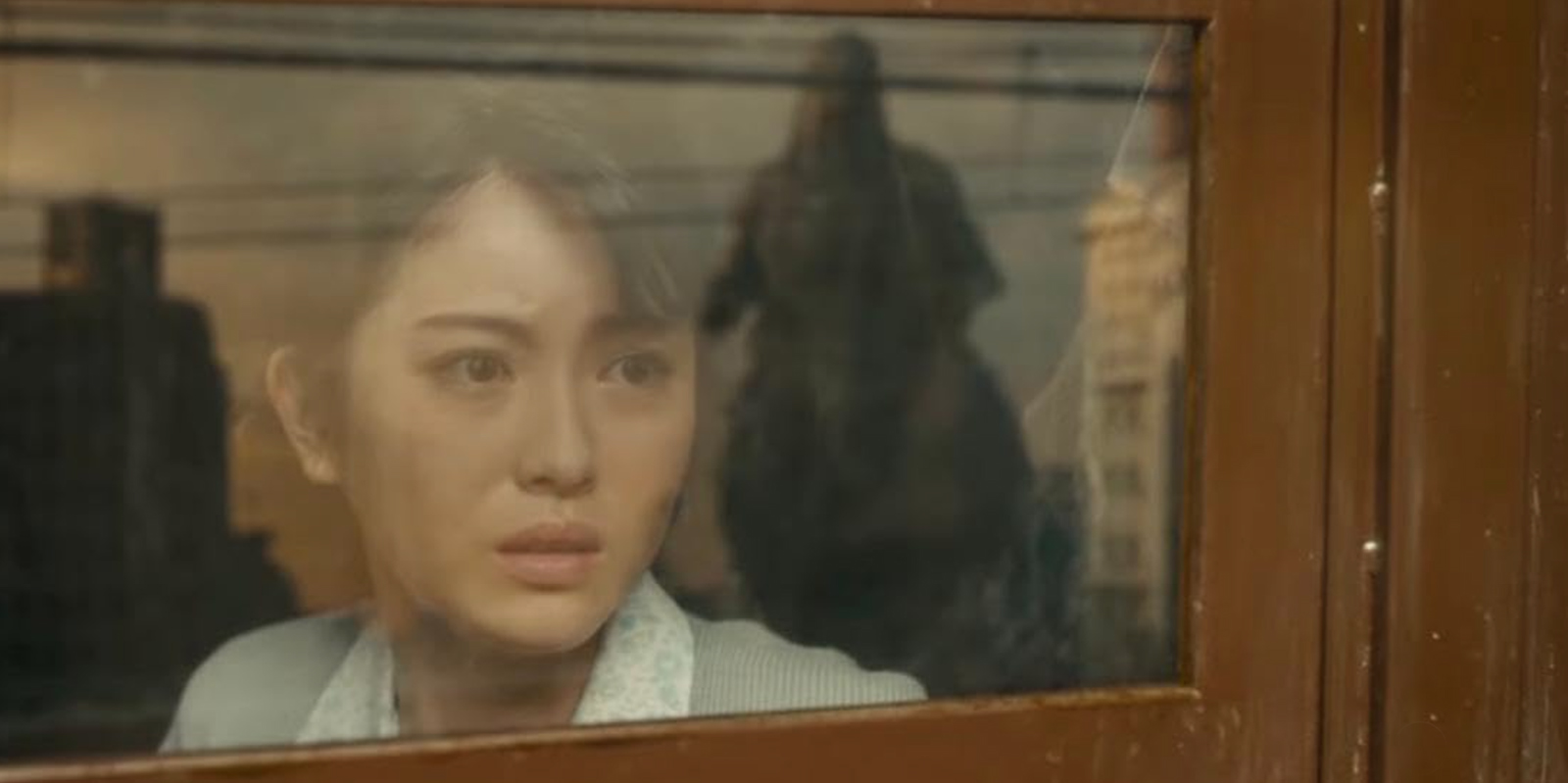

As though drawn out by his words, Godzilla emerges again, now mutated in size and given nuclear powers by American atom bomb testing. It reaches Japan, where it smashes up Tokyo’s Ginza district. In a horrifying sequence, Oishi is ripped away by gale force winds that follow one of the monster’s nuclear blasts.

People run from Godzilla in a scene from “Godzilla Minus One.” (Toho International)

It’s hard to convey how frightening director Takashi Yamazaki has managed to make this almost comically familiar character. When the monster acts, it does so in ways that are sudden, unpredictable and shockingly violent. The visual effects are disturbingly, immersively realistic. But more admirably, Yamazaki has taken the earliest Godzilla movie tropes, such as people fleeing the monster in the streets, and unlocked the horror within them.

Yamazaki thinks Godzilla needs to be understood as a spiritual force. “There is a concept in Japan called ‘tatarigami,’” he told The Associated Press, referring to powerful spirits of vengeance in Japanese culture. “Godzilla is half-monster, but it’s also half-god.”

The profound question of “Godzilla Minus One” is the nature of the crime that Godzilla has come to punish. In the early going the creature seems to be an embodiment of our pilot Shikishima’s shame, pursuing him and growing in power as his self-hatred deepens.

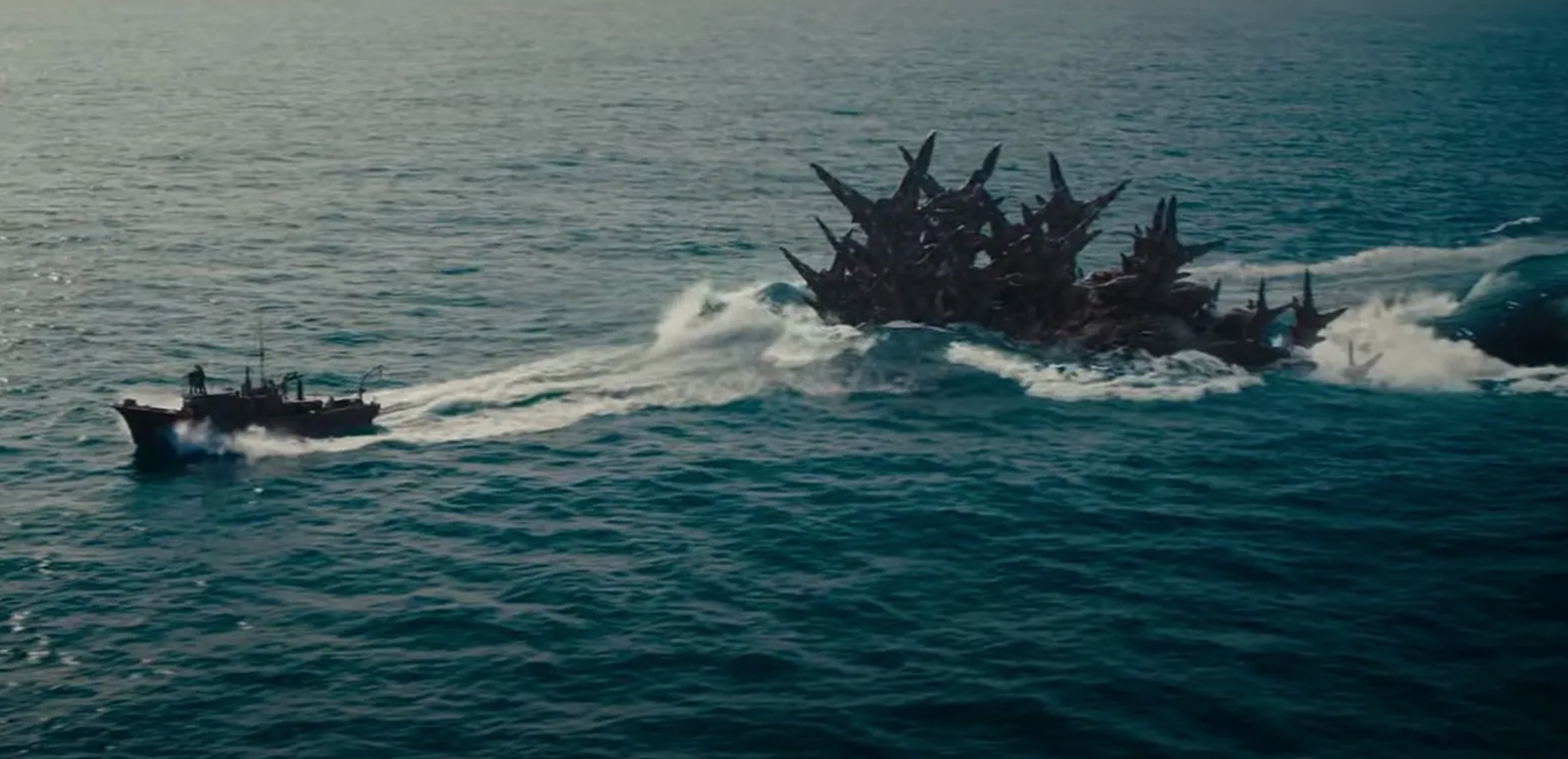

Part of Godzilla appears behind a boat in “Godzilla Minus One.” (Toho International)

But in the latter half of the film, Yamazaki widens his lens to the broader community of retired Japanese veterans who volunteer to try to stop the beast. They, too, feel trapped in the past, ashamed of having survived the war. Slowly the film comes to show that the real shame is not that they lived, but that their government placed so little value on human life: Tanks were sent out without adequate armor; planes had no ejector seats, requiring the pilots to take their own lives.

In the end, the veterans tell a man too young to have been conscripted that the greatest honor is not to have been a soldier, but never having been in a war in the first place.

Once again being asked to make the ultimate sacrifice, the veterans commit themselves to a different path: They will fight not only to save their country, but themselves. “This is not a fight to the death,” one of their leaders argues. “This is a fight for future lives.”

By its end, their plan involves hundreds of people in dozens of boats on the open sea. But having declared the sacrifice of human life as the shameful truth of war, Yamazaki has imbued each person onscreen with tremendous value, even nameless background characters. In their final battle with Godzilla, the death of a single person, known or not, constitutes a failure of the whole society.

Scene from “Godzilla Minus One.” (Toho International)

Godzilla is not a monster that you defeat, Yamazaki told AP, but a supernatural force stirred up by human sins that must be returned to its slumber. “You have to quiet it down,” he said. In “Godzilla Minus One,” what settles Godzilla is a radical communal insistence on the dignity and value of every single human life.

That plays against the morality of most of American cinema’s big-budget stories, which commonly equate self-sacrifice with heroism and apocalypse with entertainment. “Godzilla Minus One” shows that a monster film can be memorable with fantastically rendered action, but also speak to existential truths about humanity and its future.

More than 75 years after Hiroshima and Nagasaki, as Ukraine and the Mideast grind along in the shadow of nuclear threats, we all continue to live with the possibility of mass annihilation. While some recast that possibility as a cinematic thrill ride, Yamazaki suggests we consider closely what wild spirits our fantasies may be conjuring.

Scene from “Godzilla Minus One.” (Toho International)

(Jim McDermott, a former associate editor of America Magazine, is a screen and magazine writer in New York. His Substack newsletter on pop culture and spirituality is called Pop Culture Spirit Wow. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)