(RNS) — Andrew Torba, an ultraconservative web commentator, turned on the radio a few weeks ago and discovered a secret war on Christmas.

Not the one fought by “libs” on the sides of Starbucks cups or in city buses’ destination displays reading “Happy Holidays,” but by Rudolph, Frosty and a few mostly deceased Jewish songwriters.

In a Nov. 21 episode of his “Parallel Christian Society Podcast,” Torba, founder of the alt-right social media platform Gab and co-author of “Christian Nationalism: A Biblical Guide For Taking Dominion and Discipling Nations,” expressed his dismay at learning that many popular Christmas songs were written by American Jews.

Drawing mainly from a review of “A Kosher Christmas” in the Israeli newspaper Haaretz dating to 2012, Torba recounted how many of the season’s most popular songs — “White Christmas,” “Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer,” “Let it Snow” and “A Holly Jolly Christmas,” to name a few —were written by Jews.

Those songs, Torba claimed, were part of a conspiracy to kick Christ out of Christmas that turned a celebration of the birth of Jesus into a winter holiday with room for Jews. “Knowing this, how could you allow your household to be filled with this music?” Tobra asked his listeners.

Torba’s suspicions were also raised when he found that, along with ruining Christmas, Jews in America celebrate Hanukkah and that American presidents have acknowledged that Jewish holiday.

Andrew Torba in a 2018 interview. (Video screen grab via Youtube/PAHomepage)

“Wow, incredible, incredible, how this happened,” he said. “In a Christian nation, it takes this relatively minor Jewish holiday and turns it into this prominent holiday that is celebrated in our White House. Isn’t that something?”

Asked about his podcast, Torba cited the Haaretz article, which quoted the late American novelist Philip Roth describing “White Christmas” as a song that took Christ out of Christmas.

“People who hate and reject Jesus Christ, and whose faith and identity centers around that rejection, wrote subversive songs to ‘de-Christ’ Christmas,” he said in an email. “This is a problem and Christians deserve to know about it so they can adjust their listening habits during the Christmas season accordingly.”

Jonathan Sarna. (Photo via Brandeis University)

Jonathan Sarna, professor of American Jewish history at Brandeis University, suggested Christian nationalists such as Torba might want to do a little reading about American history. Firstly, he pointed out, Christmas was not really a part of America’s founding. “The Puritans were opposed to Christmas,” Sarna said.

In 1659, leaders of the Massachusetts Bay Colony approved the “Penalty for Keeping Christmas,” which imposed fines on those who feasted or refused to work on the holiday. It wasn’t until German immigrants brought Santa Claus, Christmas trees and songs like “Silent Night” with them that Americans took up Christmas with gusto. (Christmas Day itself did not become a federal holiday until 1870.)

Sarna said that the songs written by Jewish songwriters fit into the American tradition of celebrating Christmas as a seasonal celebration, rather than a religious one. “They are more in the tradition of Dickens’ ‘A Christmas Carol’ than in the tradition of ‘Silent Night,’” he said.

Jonathan Karp, who teaches history and Jewish studies at Binghamton University, said there’s no conspiracy involved with the success of Jewish writers of Christmas carols. Jewish songsmiths such as Irving Berlin wrote Christmas songs thinking Americans’ popular performers wanted them.

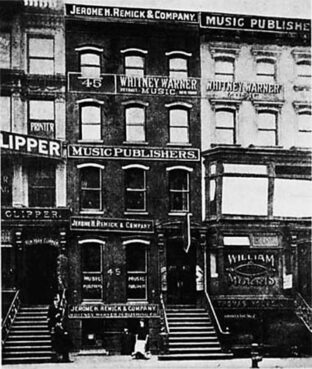

Karp said many Jews worked in Tin Pan Alley, the collection of songwriters and publishers that flourished in midtown Manhattan from the late 1800s to the mid-1990s, as well as in the theaters and venues where live music was performed.

Tin Pan Alley on West 28th Street in Manhattan, New York, in 1910. (Photo courtesy of Wikipedia/Creative Commons)

Before records came into fashion, those songwriters made their money from sales of sheet music, said Karp. One way to sell sheet music was to get popular entertainers to sing them. When the holidays rolled around, those entertainers needed Christmas songs to sing. So Jewish Tin Pan Alley songwriters wrote them.

Karp also suggested that songs like “White Christmas” were a way for Jewish songwriters to participate in Christmas — even though the religious holiday is not their own.

“I would even go as far as saying it’s about feeling the spirit of Christmas,” he said.

Writing Christmas carols isn’t the only way Jewish Americans played a role in holiday tradition. Albert Sadacca, whose Jewish family emigrated from Turkey, helped develop electric Christmas lights and helped found one of the largest Christmas light manufacturers in America.

Devin Naar, associate professor of Jewish studies at the University of Washington in Seattle, who has studied Sadacca’s part in popularizing Christmas lights, said that Christmas has become an icon of America almost as much as Uncle Sam or the Stars and Stripes. Even if they don’t celebrate Christmas, Jews have helped write this chapter of the American story.

Naar pointed to a Sephardic proverb found in the Ladino dialect spoken by Jewish immigrants from the Muslim world (like Sadacca), which translates, “Let me enter, and I’ll make a place for myself.”

Whether writing Christmas songs or creating Christmas tree lights, Jews found a way to show that they belonged in America, at a time when their fellow Americans viewed them with suspicion. In a 2022 essay for The Washington Post, Naar pointed out that Calvin Coolidge — the president who presided over the first lighting of the national Christmas tree — favored harsh immigration reforms.

Devin Naar. (Photo via University of Washington)

“America must be kept American,” Coolidge said in his first address to the nation, a few weeks before that tree lighting. By American, Coolidge meant “white Christian people, preferably Protestants,” said Naar.

The following year, Coolidge signed legislation that barred Jews and non-Europeans from immigrating to the U.S.

In the following decades, Americans became more open to those who had once been outsiders, said Naar. The Christmas carols written by Jews helped make that happen. Yet American Jews remain ambivalent about holiday traditions such as Christmas trees.

After all, there’s no way to take Christianity out of the holiday. “At the end of the day, the name of the holiday is still Christmas,” said Naar.

If Torba’s defense of Christmas is neither particularly American nor particularly religious, his antisemitism is in keeping with the ideology he espouses, Christian nationalism.

Data from a 2020 national survey found a relationship between Christian nationalism — the idea that America belongs to Christians and that Christians should run the country — and antisemitism. The more that Americans believed in Christian nationalism, the more they supported antisemitic claims that Jews have too much power in America and around the world.

“It’s a function of what psychologists call a social dominance orientation,” said Paul Djupe, associate professor of political science at Denison University. “They think that there’s a rightful order of things and that Christians should be on top.”

Despite the anger of Christian nationalism, Sarna doubted that many people know the religion of Christmas carol writers. Or care what they believe.

Most people who sing Christmas carols, he said, just want to sing their favorites.

“‘White Christmas’ remains one of the most popular Christmas carols,” he said. “People think it comes from the time of Jesus — not from Irving Berlin.”

(This story was reported with support from the Stiefel Freethought Foundation.)