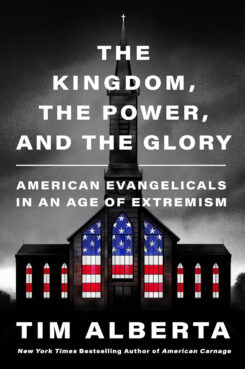

(RNS) — This week saw the release of “The Kingdom, the Power, and the Glory: American Evangelicals in an Age of Extremism,” by Tim Alberta, staff writer at The Atlantic. Already, the book has been widely covered and highly praised. A committed Christian and the son of a preacher, Alberta accomplishes in this compelling and devastating book the kind of honest examination that can only be done in love.

Here’s my interview with Tim, which has been edited for clarity and length.

You were featured on “CBS Sunday Morning” last week, and some of the online criticism of your book that popped up immediately (from the usual suspects) assigned political motivation and timing to the project. But this book isn’t just political; it’s also personal. Can you explain why that’s so?

I was raised inside the evangelical church. My father, once a wealthy New York financier who considered himself an atheist, became born again in the late 1970s and then felt called to ministry. The church he pastored for more than 25 years — our home church, Cornerstone EPC in Brighton, Michigan — was essential to my identity. As I grew older, however, some of what I saw inside of evangelicalism left me disturbed and disillusioned. I never said anything about it; I was a team player, not wanting to air dirty laundry or feed ammunition to critics of the church. Looking back now, I’m ashamed of that silence. It ultimately took a personal tragedy — my dad’s abrupt death and the ugliness I encountered at his funeral, as right-wing zealots assailed my political writings in full view of his casket — to jolt me out of complacency and confront this problem I’d tried to ignore.

Books about the “crisis” within American evangelicalism owing to recent political developments (among other things) have grown into a genre unto itself. (I’ve made my own contribution to this onslaught!) But I think one of the things that sets your book apart and makes it so important is how much of your material comes directly from primary sources — your own interviews with the subjects you write about, many of whom have played a part in creating the extremism named in the book’s subtitle.

Of course, you are a journalist (not, for example, a sociologist or historian), so in one way this is just you doing your job and doing it well. In many instances within the book, your subjects damn themselves through their own words. Yet, one aspect of the extreme polarization we are experiencing is distrust of mainstream journalism. What are your hopes that the work of journalism in general — and yours specifically — can make a difference in this moment and for evangelicalism in particular?

“The Kingdom, the Power, and the Glory: American Evangelicals in an Age of Extremism” by Tim Alberta. (Courtesy image)

The church’s great weakness at an institutional level — and to be clear, this is common among all institutions — is an unwillingness, and perhaps more commonly an inability, to police itself.

We have seen this time and again. Whether the setting is a small independent congregation or a large denomination with a centralized polity, the mechanisms necessary to ensure transparency and accountability often do not exist, and where they do, they often go unused. This presents an obvious challenge. Institutions need oversight, yet religious bodies are known to chafe at external meddling, especially from secular sources.

Journalism, when practiced diligently and ethically, provides accountability in powerful ways — regardless of whether the reporting is done by a believer or not. That said, there is something uniquely credible about a Christian scrutinizing his or her own faith tradition, because the intent is self-evidently not to hurt the church but rather to help it. Speaking only for myself, I view journalism — particularly this genre of journalism — as an exercise in shining light into darkness: not simply exposing what is wrong and false, but illuminating what is right and true.

Throughout the book, one recurring question you raise is whether leaders —be they pastors, politicians or social media personalities — who have gained so much (monetarily, politically or socially) are knowingly and opportunistically peddling fabrications, or whether they really believe these deceptions. In other words, are they misleading or misled? Or both? Of course, the answer to this varies from person to person. But stepping back and looking at the big picture that has been created by so much misinformation, what do you think has contributed most to this current state: manipulation or gullibility?

In scrutinizing people operating at levels of leadership — the so-called shepherds charged with leading congregations, ministries, etc. — the conclusion I have reached is that almost all of them know better.

These are not dupes; these are not true believers who have sincerely bought into the crazy, conspiratorial nonsense that has captured the imaginations of their followers. There are exceptions to this; in studying Eric Metaxas, for instance, there is evidence to suggest he has succumbed, at a deep psychological level, to dangerous misinformation.

But in the vast majority of cases — whether it’s Ralph Reed or Robert Jeffress or even Greg Locke — I have walked away from long, searching interviews convinced they’ve made a decision, a business decision, to indulge a lot of foolishness.

Why? Because in their view the ends justify the means: Trafficking in deception and hatred is a small price to pay for a seat at the table, for a culture war victory, for a reclamation of our nation’s Christian heritage. The problem is, Scripture describes those ends as unimportant — while telling us, repeatedly, that the means are crucially important. In other words: How we play the game matters more than whether we win or lose. That’s a message that rank-and-file evangelicals need to hear, but many of the people they look to for influence have real incentive to tell them otherwise.

After interviewing a number of pastors who have discovered, as you say, “that wrath is a business model” and “crazy is a church growth strategy,” you make the keen observation, “It turns out, when a pastor decides that churches should do more than just worship God, congregants decide that their pastor should do more than just preach.” Yet, you’d surely agree churches must disciple their people, too. Based on all you’ve chronicled, what wisdom can you offer that would help discipleship not turn into political indoctrination?

At one point in the book, a prominent political activist, who had been touring churches nationwide in an attempt to rally evangelicals around Republican causes, told me there was one way to ensure Christians vote biblical values: “Pastors need to preach politics.” But this struck me as completely backward. As I responded to this man: “If pastors were doing their job — going deep in the word, discipling their flocks, stressing Scripture and prayer above social media and talk radio — their people wouldn’t need to be infantilized with explicit partisan endorsements. Those Christians would know how to vote biblically, because they would know their Bible.”

On a related note, later in the book you observe, “The scandal is that Christians, someplace deep in their hearts, possess that … Christlike love. But they have been conditioned to subdue it. They have been taught to selectively practice habits that are meant to be universal.” Is this perhaps an area where good teaching and discipleship are most needed?

Tim Alberta. (Courtesy image)

Yes, I believe so. The first step is rebalancing the consumption ratio inside our churches. Right now the amount of extrabiblical content we take in — via cable news, talk radio, social media — is wildly disproportionate to the time we spend in God’s word. Those sources have conditioned many evangelicals to be angry, fearful, antagonistic. Yet this need not be a permanent condition. Every crisis presents an opportunity. In this case, the crisis of political extremism in our congregations presents pastors and church leaders with an opportunity to disciple their flocks in daring new ways, challenging them to revolutionize their information-intake habits and re-center their lives in Scripture and biblical teaching. It won’t happen overnight. But I believe a sustained push will eventually yield real change in behavior among these everyday Christians who, I firmly believe, do possess that Christ-like love in their hearts.

I’ll be honest: The book was a hard read for me for a couple of reasons. One is that I know many of the people whom you interview at length. A few of them are ones who have disappointed me greatly in the turns their leadership has taken. But most of them have been, like me, hurt and betrayed by people and institutions you write about. Another reason the book became heavier and heavier as I was reading it is that the first two-thirds of the book was so male-dominated. I began to despair that either you had left out women’s voices — or worse — that women’s voices matter so little within evangelicalism. And then all of a sudden, the book took a turn, and the women appeared. Was this intentional on your part or is it just a natural reflection of the way the story — your story and the bigger story — took shape?

Karen! Very perceptive. Yes, it was intentional — both to demonstrate the degree to which women have been marginalized and treated as second-class citizens within the evangelical movement, but also to highlight the singular ways in which women have fought for truth and accountability inside the church. Doctrinal disputes notwithstanding — and I certainly believe Christians can have good-faith disagreements about complementarianism, egalitarianism, etc. — it’s just painfully obvious that evangelicalism has suppressed women’s voices in ways that exacerbate this crisis of credibility facing organized Christianity in America.

You quote two of the women you interviewed — two sexual abuse survivors, Jules Woodson and Tiffany Thigpen — as coming to the sober realization real change is going to take people working from the outside-in because churches simply will “never hold themselves fully accountable.” I guess this brings us back to one of my earlier questions. Did you write this book hoping to be part of that accountability?

I’ll let my earlier answer to this point speak for itself, since I’ve been long-winded already.