(RNS) — Since the Oct. 7 attack on Israel by Hamas, and Israel’s retaliation in the Gaza Strip, mainstream U.S. Jewish leaders and institutions have rushed to throw their support behind Israel and relatedly Zionism, the political ideology that led to the founding of the state in 1948.

They have also equated any criticism of Israel, or any anti-Zionist sympathies, with antisemitism. Perhaps most notably, Jonathan Greenblatt, CEO of the Anti-Defamation League, has repeatedly said anti-Zionism equals antisemitism.

But there is a growing group of U.S. Jews (including several Haredi Orthodox groups) that dissent from the Jewish American’s unstinting support for Zionism. Among them, the groups IfNotNow and Jewish Voice for Peace have stood up traffic on highways and shut down transportation hubs to protest the Israeli assault on Palestinians in Gaza.

There is also a growing body of scholarship reckoning with Zionism.

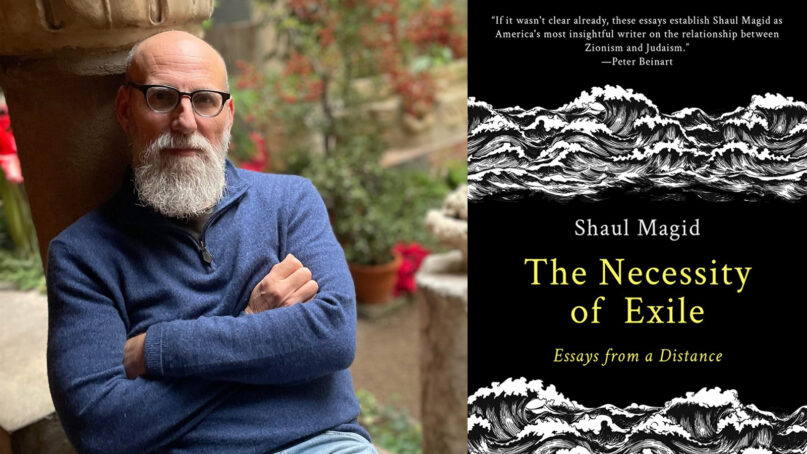

One such scholar is Shaul Magid, a distinguished fellow of Jewish study at Dartmouth, and this year a visiting professor of modern Judaism at Harvard. Magid is also a rabbi who leads a summertime synagogue on Fire Island, a resort community off the coast of New York.

In his new book of esssays, “The Necessity of Exile: Essays From a Distance,” Magid argues that Zionism has accomplished what it set out to do — to be an ingathering for Jews. Now it has become a “chauvinistic ideology” that, by denying Palestinians an equal right to self-determination, has become illiberal at its core.

Zionism’s raison d’etre was to negate the notion of exile and wind down Jewish life in the Diaspora. Zionists see themselves as the center of Jewish life and all other Jews at the margins. Magid would like to see a reevaluation of exile as a positive and constructive alternative to the Zionist project.

Religion News Service spoke to Magid about his position, which he calls “counter-Zionism,” in a phone conversation earlier this week. The following interview was edited for length and clarity.

Where are you at religiously?

I’ve had a pretty circuitous journey. I grew up as a secular Jew in the New York suburbs, I had a bar mitzvah like everybody else in my generation. In the late 1970s, I became a baal t’shuva (one who returns to tradition). For about five years I lived as a Hasidic Jew, mostly in Jerusalem, but also partly in Brooklyn. I ultimately left the Orthodox world. After I received rabbinical ordination in 1984, I went into academia at the Hebrew University. I moved back to the U.S. in 1989 to do a doctorate at Brandeis University in Jewish thought that I completed in 1994.

You don’t view yourself as an anti-Zionist but as a counter-Zionist. Explain what you mean by that.

Shaul Magid. (Courtesy photo)

The reason I’m not an anti-Zionist is because when people use the term anti-Zionist, they usually mean that they’re against the very existence of the state of Israel. And I’m not against the existence of the state of Israel. I make a distinction between Zionism as an ideology and the existence of a state. Even though Zionism was the ideology that brought the state into existence, I feel it’s done its work and it is no longer the best ideology to think about coexistence with a very significant non-Jewish population in the state that’s not going anywhere.

I served in the Israeli army in 1989 during the first intifada where I came to see what was going on firsthand— the hatred in the eyes of these Palestinian children when you’re walking through their villages — even if you’re not doing anything to them. And I came out of the army feeling very disillusioned, like, this is a terrible situation and Zionism doesn’t provide much of an alternative. So I started to really think, why are we so attached to the ideology of Zionism? Why can’t we just put that on the history shelf and think about another way of dealing with this?

Your book was written before Oct. 7 and in it you advocate for a one-state solution. Is that still something you envision is possible?

I would call it a one-state reality. The reality on the ground is such that a two-state solution is not really that viable anymore, in my view. So what kind of state is it going be? I think the energy should be used to make it more of a democratic state. As I see it, it’s really teetering on being an apartheid state, if not already an apartheid state. In any case, it’s a state of Jewish chauvinism and domination. I don’t think that’s even provocative to say. When the war ends, the problems that existed about Zionism will still be with us. I don’t see that there’s political will in Israel now for a two-state solution. While understandable on some level, it is also very troubling, even tragic.

Is Zionism different from any other kind of nationalisms?

That’s a great question. Zionism is a particular kind of nationalism. What is distinctive in Zionism is that the Jews see themselves in the land of Israel as simultaneously settlers and natives. I think that’s distinctive because you have colonial projects where you have people going in colonizing a place and they’re the settlers, like the French in Algeria. But with Zionism you have people coming from Europe back to the land of Israel and not only claiming they’re coming to settle the land, but claiming they’re actually native to the land, having been disempowered for millennia. What ends up happening is that when Europe starts to really collapse in the 1930s, the “Arab Question” gets pushed aside and it just becomes an emergency situation and nobody was really thinking about how to solve that problem. That problem still exists in 2023.

As you explain, Zionism in some ways came to try to end the Jewish exile. But the exile hasn’t ended for half of the world’s Jews. Why is exile perceived negatively by Zionists?

“The Necessity of Exile: Essays From a Distance” by Shaul Magid. (Courtesy image)

I think there are two categories that are operative. Exile is really a theological, one might say, religious category. And then there’s a category of diaspora. Diaspora is a Greek term used to define any migrant community that sees itself as dispossessed from its homeland. Exile often has a negative connotation, in Judaism a divine punishment for collective sin. It means separate from, alienated from. What I argue in the book is that exile doesn’t necessarily have to be negative. It can actually be positive. It can serve to counter the kind of domination that I think occurs once Zionism claims, even by implication, that the period of exile is over. There’s a very dark side to that power and domination and you lose a sense of humility that is embedded in this notion of exile — the idea of “not yet” — that it’s not over yet. Jewish exilic history has not ended with the establishment of the state of Israel. So I’m trying to show how exile can function positively for a community that’s living in the Diaspora but even for a community that’s living in its own sovereign state. Exile is potentially very constructive. Judaism as a religion was created in exile. That was an incredible feat, right? And so there’s a lot of creativity and energy being in that state of “not yet.” Abandoning that is very dangerous, in my view.

How do you explain why the major religious movements in the United States are so fixated on support for Zionism and Israel?

There is this real erasure of American Jewish history in the 20th century. Until the establishment of the state of Israel in 1948 most American Jews were not Zionists. There was a real ambivalence about Zionism. That began to change after the Six-Day War and the triumphant and surprising victory wiped away a lot of the ambivalence of Zionism so that to be a Jew in good standing meant to be a Zionist. Being pro-Israel was what being an American Jew was about. Now young Jews have been brought up to believe in the centrality of the state of Israel and yet they see the country that Israel has become and many are saying, “No, I can’t support that.”

Can American Jews reimagine a Judaism that’s not embedded within Zionism?

Zionism has at least in some way replaced Judaism. You can be a totally nonbelieving Jew who doesn’t have any feeling about Judaism, and that’s fine. But if you’re not a Zionist, if you don’t support Israel, you’re not welcome. There’s something that’s quite troubling about that. We have to get back to reconstructing a certain kind of new Jewish identity for the Diaspora. Israel will always be a part of it, for or against, but it should not be the center.

Do you have a legion of detractors for writing and saying these things about Zionism?

Oh yes. But to some degree I have a bit of a bulletproof status. I have the bona fides. I spent time in the ultra-Orthodox world. I have expertise in the literature. I write about many aspects of the Jewish tradition. I have all the boxes checked. So if somebody wants to criticize me, they can’t criticize me on the question of authenticity, and that goes a long way. There are a lot of very talented people who are younger that are a lot more vulnerable and susceptible to these kinds of things. I’m 65 years old. I don’t care what people say. That kind of criticism doesn’t really matter to me anymore. And, you know, a white beard helps. For better or worse, it’s true.

Do you see more people willing to challenge Zionism within the American Jewish community?

Yes, I do. We’re watching a post Oct. 7 schism of sorts in the American Jewish community. I think a lot of young people are fed up with the baseline you-have-to-support-Israel-whatever-happens. The establishment is pushing back very hard by saying, “If you don’t support the war or if you think it’s a genocide, you’re not really part of the Jewish people anymore, you’re an un-Jew, you are ‘self-ostracizing.’” It’s really throwing down the gauntlet to say Jewishness now is going to be dependent exclusively on how one views Israel. I think it’s a big mistake. It’s about creating a schism, policing boundaries. And as we know from history, those things never end well.