(RNS) — Rabbi Sharon Brous is one of the most prominent rabbis in the U.S., known for injecting Jewish life with a bold, passionate and justice-driven ethic, whether its the need to fight racism, build affordable housing, or oppose the Israeli government’s lurch to the right.

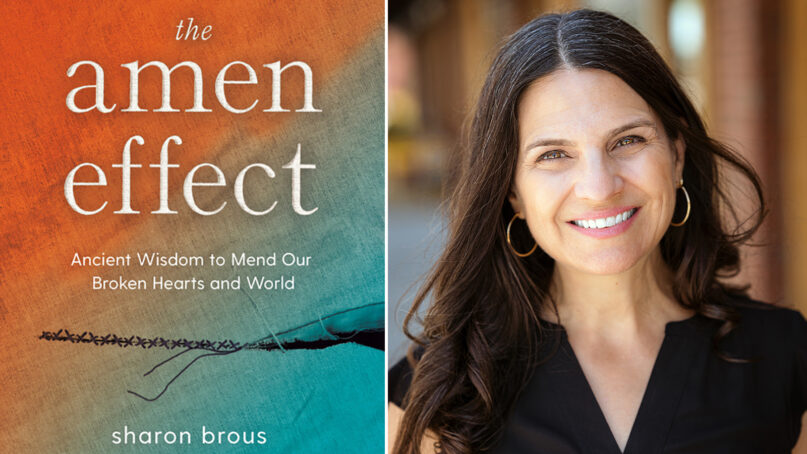

But as her new book, “The Amen Effect,” shows, she is also one of the most pastoral and caring.

The book, which draws on ancient rabbinic wisdom and personal anecdotes, is an extended meditation on the importance of “showing up” — in good times and bad. The 50-year-old rabbi and co-founder of the nondenominational IKAR synagogue in Los Angeles suggests the antidote to the plague of loneliness and isolation is compassion and community. Brous calls readers to lean in to other people’s pain and suffering and to view heartfelt encounter as a sacred act.

She roots the book in an ancient Jewish ritual in which pilgrims circled the Jerusalem temple in the opposite direction as the “ill, the bereft and the bereaved,” so the pilgrims could see and comfort them. It’s a similar idea to the book’s central theme, the “amen” recited by the community at several points during the kaddish or mourner’s prayer, in which the community affirms mourners in their time of grief.

Though it draws on Jewish ritual and practice, the book is intended for a wide audience of both religious believers and people of no faith.

Religion News Service spoke with Brous during a book tour stop that took her to New York City. The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Explain the idea of the “amen effect” and how it came to you.

“The Amen Effect” by Rabbi Sharon Brous. (Courtesy image)

This emerged from my realization that this very old mourner’s prayer that you say after a loved one dies is a powerful expression of solidarity and support from a community to a mourner who’s in a moment of anguish. It’s a way a community can create a container to hold and help reorient a person in their loss. Amen is a very old word. It goes back to the Hebrew Bible and it’s a word that also is used in other traditions, in Christianity and in Islam. And it occurred to me that the act of saying amen was an expression of affirmation of a person’s experience. It’s a relational word; we say amen to someone else’s prayer. We almost never say amen to our own prayers. And so, built into the act is seeing, affirming, honoring another person’s experience. It struck me that in this time of loneliness, social alienation and disconnection that amen is fundamentally a word of connection. The amen effect is what could happen in our hearts and in our society if we root ourselves in that kind of powerful expression of connection and affinity for another person in our times of joy and also in our times of heartache.

As you point out in the book, it’s not the words or the message of the mourner’s prayer that are as important as the act of saying it in community.

That’s the power of ritual — that in some ways it even transcends the words. Some people will resonate very much with the words of this ancient prayer written in Aramaic. But the choreography of the prayer, its dialogic nature, the fact that it’s brought into community precisely at the moment that we feel the most upside down — that’s what struck me as so powerful about this ritual.

Your Grandma Millie is central to the book, especially her saying about showing up for a simcha or celebration. Did she know something that maybe society has forgotten?

I think she understood how fragile life was and that if we don’t grab the moments of joy when we can, we are depriving ourselves of the fuel that we need to survive through the challenging and painful moments. And that’s a wisdom that she shared a lot in her old age. It’s a perspective that’s obviously rooted in experiences of heartache and probably, I would imagine, missed moments that led her to recognize how critical it is that we do actually show up for one another when we can for those moments of joy.

You mention that your synagogue drafted a strategy to counter the problems of isolation. Tell me a little bit about that strategy.

Shortly after COVID started, we realized there was this epidemic of loneliness and that once we were forced to physically separate from each other, many people lost whatever anchors they still had in the universe. I had one particularly distressing conversation with a young woman and she expressed that coming to synagogue on Shabbat once a week was the only time she felt that people knew if she was dead or alive. With the restrictions on gathering, she grew fearful that she might die and nobody would know. Once I heard this congregant express her fear, I held an emergency clergy meeting and we decided that we had to devise a strategy where we were going to really try to be in touch, with some regularity, with literally every person in the community to just let them know that they mattered to us and that we were not going to let them untether from this world. And I have to say it was extremely challenging. Our community is not small anymore. And we didn’t get it right all the time. But we were very deliberate about making pastoral calls for no purpose other than just to say, ‘It matters to me that you are alive in this world.’ Part of what we’re trying to do is destigmatize loneliness and help people find each other when their instincts tell them to retreat from one another.

People often retreat or flee from other people who are grieving or going through pain. Is it because because they don’t know what to say or it’s just awkward. How do you deal with that?

I think there are a lot of reasons why people pull away from presence in those moments.

Other people’s losses make us feel very vulnerable. It forces us to confront the possibility of our own loss and that’s very real. So we tend to avoid it. It makes us feel destabilized. If someone else loses a child, it forces us to confront the possibility that we too are vulnerable to potentially, God forbid, losing a child. So we pull away from those who’ve experienced loss in exactly the moment when those people need community the most.

I’m a mourner now. My father died just before Rosh Hashana. I know it can be overwhelming. And so I think that’s another reason why people stay away. We don’t want to impose; we make assumptions about how other people are grieving. But it could end up being very hurtful because it could lead to a real sense of abandonment, even for people who do have a lot of folks present for them. And so my rule, which is an extrapolation of my grandma’s rule, is to err on the side of presence. We should just show up and show up in sensitive ways and in humble ways and allow for the possibility that it’s not the best time for the person to see us.

You also write about the fact that as a rabbi you hear about people’s pain all the time and that can be exhausting; it can lead to compassion fatigue. How do you deal with that?

People who are oriented toward caregiving are very resistant to set boundaries on that care, often at the expense of their own physical and emotional health. I believe it is critical for caregivers to understand that we all need to allow ourselves to be held by a community of care and concern that can see us and hold us in our struggle. As a rabbi, I’ve had to really fight to reinforce among the caregivers in our community that it’s OK to take a meal train when your kid is having surgery and you don’t have time to make dinner. It’s always the people who are the first to bring over the lasagna to someone who is hurting who are most resistant to having the community come and take care of them. But what I receive when I’m being cared for will only help me become a better caregiver when I return to the work.

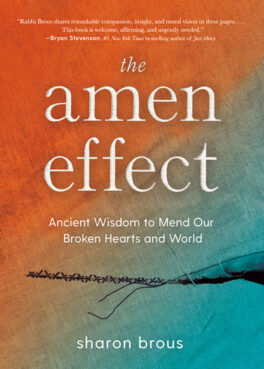

The cover of the book is an image of a mended or restitched garment, which you explain in relation to the Jewish custom of “kriah,” or tearing a piece of clothing as an expression of grief. But most people aren’t aware of the tradition of mending.

The cover was designed by a dear friend, Lawrence Azerrad, who had just lost his mother and we had just walked through with him the rituals of grieving, including the tearing of a garment, which is essentially an externalizing of the tear of our hearts. It’s an expression of our brokenness and a way of signaling to ourselves and others that we are not OK. So we wear that torn garment throughout the shiva. But the ancient rabbis were very practical people and they asked this question — what if a person doesn’t have a lot of clothing? What are they supposed to do with a torn-up shirt or dress or jacket? And they decided that after the shiva is over, one can stitch it very roughly with a different colored thread so anybody who gets fairly close will be able to see that you’re a person who’s been all torn up, but you’re on the mend. And then after a full month has passed, you can stitch it up with much finer stitches so only someone who gets really close to you can now see how torn apart you’ve been.

The image resonated so profoundly for me. It feels impossible to imagine that we can ever stitch ourselves back together, but we can. And in some ways, it becomes even more beautiful than it was before because now it holds the history of the struggle and of the process of healing. And that’s my deepest prayer for us as individuals and for our society.