(RNS) — This weekend (Feb. 2-4), as for the past six years, the immigrant aid organization HIAS and participating synagogues will observe Refugee Shabbat to reaffirm the Jewish value of welcoming and protecting the stranger. The event was born with a tinge of tragedy: The murderer who showed up to kill 11 Jews at the Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh was fixated on HIAS (founded as the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society) and the inaugural Refugee Shabbat, in 2018.

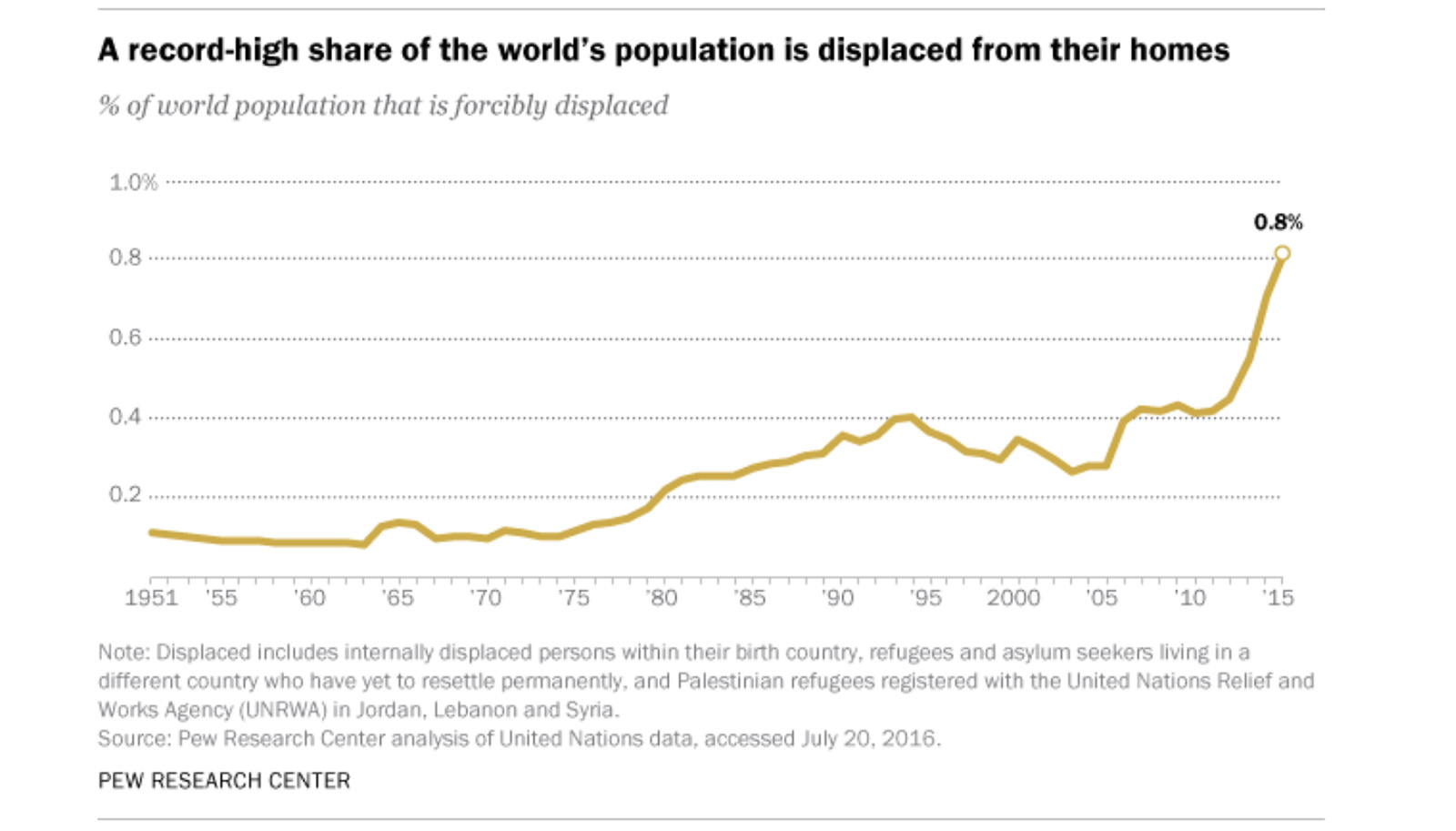

This is all the more reason for us to embrace it. And this is also the right time to place the earth’s millions of wanderers at the top of our agenda. As a 2016 Pew analysis shows, since 2005 the world has witnessed an exponential rise in refugees, asylum-seekers and those internally displaced.

“A record-high share of the world’s population is displaced from their homes” (Graphic courtesy of Pew Research Center)

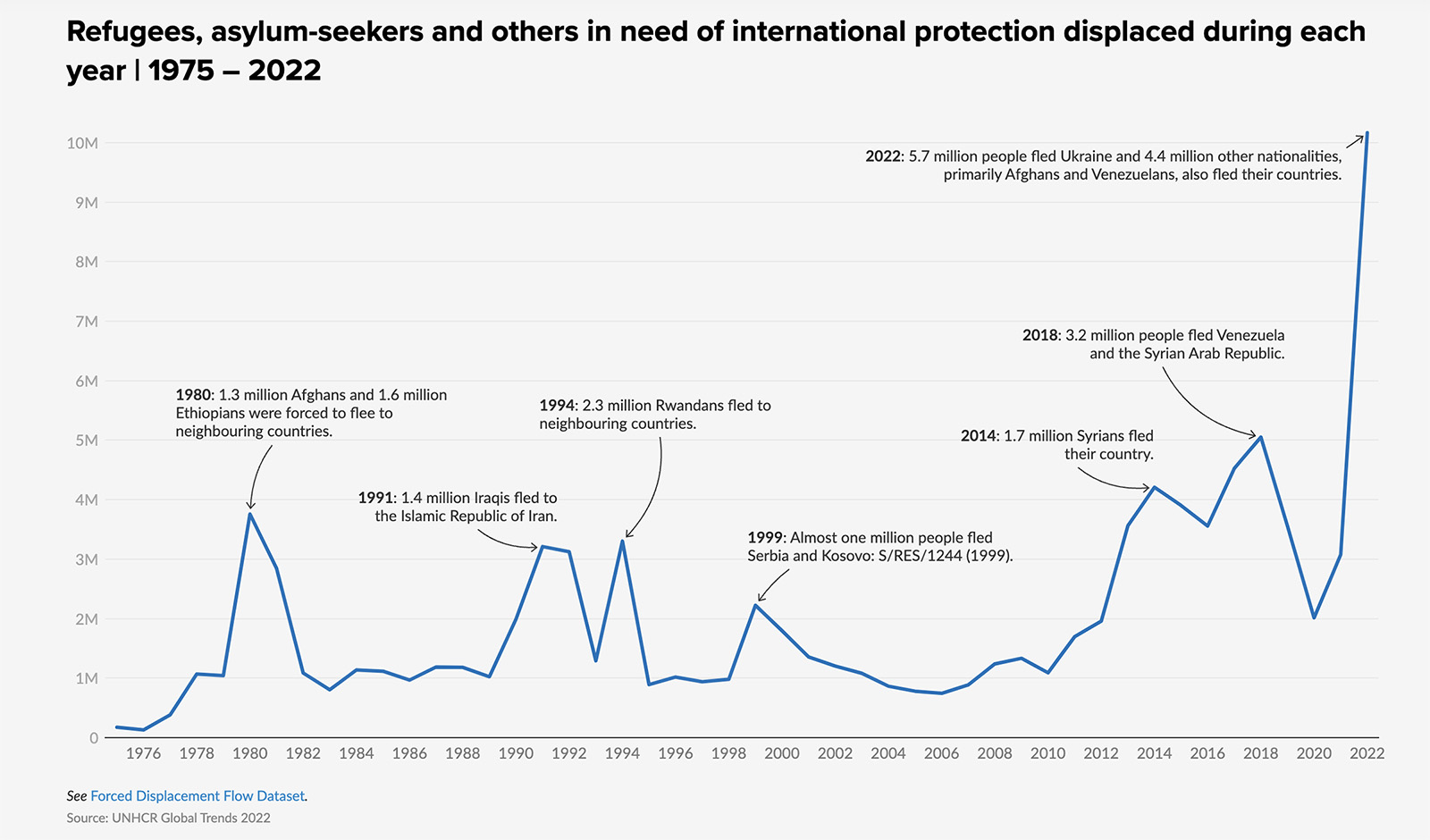

In the years since Pew did that analysis, the number of displaced people has increased even more dramatically, to upward of 110 million people as of June 2023, or more than 1.2% of the world’s population, according to the U.N. Refugee Agency. As the chart below shows, there was an enormous spike in 2022, which doesn’t even take into account the massive internal displacement in Israel and Gaza since Oct. 7.

“Refugees, asylum-seekers and others in need of international protection displaced during each year | 1975 – 2022” (Graphic courtesy of UNHCR)

As we look around today, we see so many wandering far from home — those flocking to the United States’ southern border in record numbers; war refugees from Ukraine; people streaming from Venezuela, Myanmar, Sudan, Afghanistan and Syria.

Hundreds of millions are climate refugees, from Bangladesh to California. According to U.S. Census Bureau data, 3.2 million U.S. adults were displaced or evacuated due to natural disasters in 2022, of whom more than 500,000 had not returned by the beginning of 2023. And let’s not forget those in America who are housing-insecure for financial reasons, a number that has been on the rise since 2017. It’s not just in California or big cities.

Can this disturbing trend now be reversed? Perhaps it can, if these staggering numbers can help us to see this as a shared crisis, truly global and universal. Leaving home is a quintessential human experience. Even those currently at war with one another can relate, on some level, to those exhausted, bleary-eyed faces on the other side of the fence.

Recently, I’ve been packing up my home of 30 years, in preparation for my retirement. I’m making no comparison between my situation and those of refugees and asylum-seekers. I am not suffering, not in the least. But, living in a parsonage I do not own, I have to move, with all the associated feelings of displacement and disorientation, where down is up, here is there and things feel out of whack. Each decision becomes an existential dilemma. Do I save or discard my fourth-grade math homework? What about that grainy photo of my great-grandparents that my mother left when she died? And when I get to where I am going, will it feel like home?

One can plausibly argue that the yearning for home is the strongest human impulse, an instinctive one. Whatever its basis, the restoration of “at-homeness” is a return to a sense of wholeness and balance.

It is heartbreaking to see images of destroyed and uprooted communities in Israel and Gaza: children ripped from their swings and seesaws, Jews from their synagogues and Muslims from their mosques, farmers from their greenhouses, and people from houses where they had lived for generations.

Israelis evacuate a site struck by a rocket fired from the Gaza Strip, in Ashkelon, southern Israel, Oct. 9, 2023. (AP Photo/Ohad Zwigenberg)

For Israelis and Palestinians alike, all the politics, all the fighting, all the turmoil comes back to one simple wish — to return home and be safe there, wherever home may be. Like many refugees from that region, I carry in my pocket every day the key from my childhood home that my parents sold 40 years ago.

Let me state clearly that the brutality of the Hamas pogrom of Oct. 7 stands alone in its cruelty. But the experience of displacement is a fate that people on all sides of this conflict now share. From that shared suffering might possibly arise some sympathy and goodwill.

The Book of Psalms is a remarkable collection of poems encompassing the full spectrum of life experience. Psalm 137 offers a GPS for dealing with displacement. It begins, “By the rivers of Babylon, there we sat down, we also wept, when we remembered Zion.”

This Psalm takes us on a journey from exile to restoration, from homelessness to the promise of return. It begins by those rivers, where tormentors forced the Jews to sing songs of their home. But singing those songs was just what they needed. For in doing so, they learned how to sing the songs of God on alien soil.

It’s not easy to do, but they did it. They set up entirely new institutions so that they would not forget Jerusalem. They called them synagogues. They set up Hebrew schools. They wrote down from memory all the stories and laws that had sustained them back home, all those things they took for granted all those centuries. They painted verbal pictures of what life was like back there in Jerusalem, so their children would not forget.

They collected all these stories and laws and customs into a single scroll, which they called the Torah. And these people came to be known by an entirely new name — not Israelites but Jews. And that Torah they wrote would begin with the Hebrew letter bet, the letter that means and physically depicts “home.”

All this happened by the rivers of Babylon. In the face of utter homelessness, they faced Jerusalem and held it up above their highest joy. Disregarding their sorry lot and defying their tormentors, they forged a new destiny. And then, the enemy was destroyed, and redemption was at hand.

Psalm 137 is truly a snapshot of a single moment of triumph in Jewish history. The triumph of memory. This psalm marks the moment when the home team learned how to win on the road.

Our planet is filled with people on the move. We have to learn how to survive on the go and then to help our neighbors survive — because our flooded shorelines, parched fields and heightened regional tensions over water and food supplies are only going to get worse.

Rabbi Joshua Hammerman. (Courtesy photo)

And we have to understand that despite our massive differences, all of us share an innate longing for home.

(Rabbi Joshua Hammerman is the spiritual leader of Temple Beth El in Stamford, Connecticut, and the author of “Mensch-Marks: Life Lessons of a Human Rabbi” and “Embracing Auschwitz: Forging a Vibrant, Life-Affirming Judaism That Takes the Holocaust Seriously.” The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)