(RNS) — “Our system needs to be broken,” Ted Johnson told a Politico magazine reporter recently, explaining why he plans to vote for Donald Trump.

The 58-year-old Johnson and I grew up just a few years apart in Centralia, in south central Illinois. Named for the Illinois Central Railroad, which formed the town in 1853, Centralia is surrounded by rich farmland, but it was long known for its oil fields and coal mines. In 1947, Centralia’s No. 5 coal mine exploded, killing 111 miners. Woody Guthrie memorialized the event in his song “The Dying Miner.”

Centralia’s population was close to 16,000 when Johnson and I were growing up there, but by 2020 it had fallen to about 12,000. A few years ago the Hollywood Candy Co., maker of Payday candy bars (now made by Hershey), shut down, just one episode in Centralia’s economic misfortune.

I left Centralia to attend the University of Illinois and now live in Atlanta. Johnson, after 22 years of military service, retired as a lieutenant colonel and now lives in New Hampshire, working as a senior project manager for an IT security company. Johnson told Politico that he twice voted for Barack Obama but now wants the system to be broken by Trump.

Johnson and other Trump supporters, the article says, seem to be driven by “an explicit sense of vengeance.” Johnson feels that people — apparently “other” people, since Mr. Trump is not included — should be held “accountable” for breaking the law.

A video of then-President Donald Trump is shown on a screen as the House select committee investigating the Jan. 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol holds a hearing, on Capitol Hill in Washington, Oct. 13, 2022. (AP Photo/J. Scott Applewhite)

Johnson concludes that “it’s a zero-sum game,” and he wants “somebody that’s going to take care of the average guy.”

One photo in the article shows a cross prominently displayed in Johnson’s home. That image, and Johnson’s use of the phrase “zero sum,” led me to reflect on how Jesus’ teachings are the opposite of a zero-sum game.

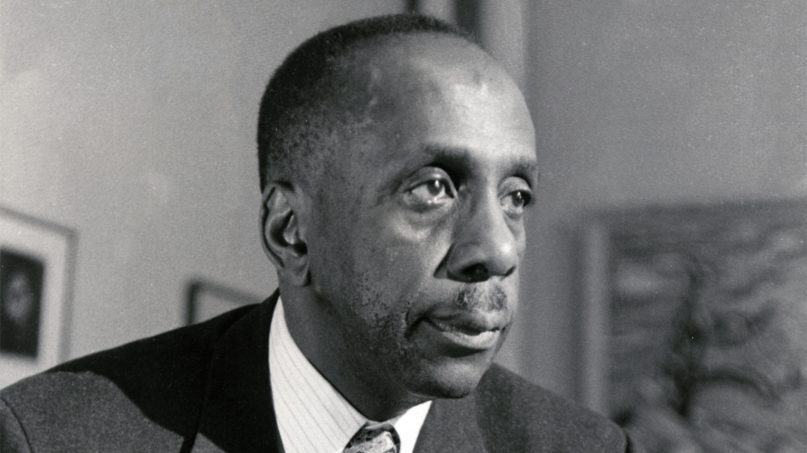

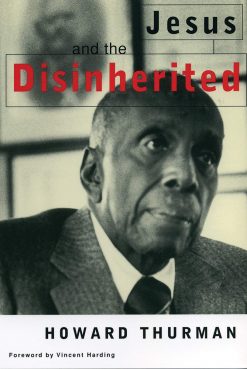

In his 1949 book, “Jesus and the Disinherited,” Howard Thurman, the theologian and mentor of civil rights leaders such as Martin Luther King Jr., recognized Jesus of Nazareth as an impoverished, first-century Jew who was a member of a politically, militarily and economically oppressed minority. That book captured the essence of who Jesus was and what Jesus meant for those disinherited like him, with their “backs against the wall.”

It also explained the ethical imperatives for those whose backs — like Johnson’s, apparently, and mine — are not against the wall. In a parable about sheep and goats, Jesus points out that human beings will be judged based on how they treat the “least of these” — the hungry, thirsty, stranger, immigrant, ill-clothed and imprisoned. Similarly, in the parable of the Great Dinner, the more comfortable can avoid such judgment, Jesus said, if they don’t invite their friends or neighbors to dinner, but instead “invite the poor, the crippled, the lame, and the blind.”

If they help the disinherited without expecting anything in return, God will reward them “at the resurrection of the righteous.”

“Jesus and the Disinherited” by Howard Thurman. Image courtesy of Beacon Press

In a “zero-sum” game, by contrast, those consumed by anger and vengeance focus on their ill will toward or even hatred of the “other.” This bears a cost on society in general and, especially, for the angry and vengeful. In “Jesus and the Disinherited,” Thurman argues that hatred destroys “the core of the life of the hater.” While it lasts, its effect seems positive and dynamic: “But at last it turns to ash, for it guarantees a final isolation from one’s fellows. … Hatred bears deadly and bitter fruit.”

I cannot accept that we are doomed to live in a “zero-sum game.” I believe, as the late Sen. Paul Wellstone of Minnesota said, that “we all do better when we all do better.”

Thurman often made a similar point. He stressed the connectedness of humanity and argued that “I cannot be satisfied in Heaven if my brother is in Hell. … I cannot be at peace in my wholeness, if you are in part; I can never be what I ought to be until you are what you ought to be.”

Members of the human community, in other words, all of whom are of infinite worth as children of God, participate in a collective destiny.

What’s curious about Johnson’s political stance, which seems to infect much of our politics, is that his “zero-sum game” approach contributes to everyone’s oppression at the hands of the wealthy. Heather McGhee’s 2021 book “The Sum of Us” argues that a zero-sum game perspective usually benefits a small group of wealthy individuals, showing that oppressing the “other” is often a “canary in a coal mine”: Systems that exploit the disinherited usually move on to exploit other groups. The people who support oppression because it hurts the “other” ultimately find themselves similarly oppressed.

No Centralian can hear “canary in a coal mine” without thinking of the coal mine disaster in our town. The wealthy and powerful who oversaw the mine refused to respond to safety warnings, and 111 innocent people died.

McGhee observes, like Thurman, that exploitation of human beings occurs when an “in group” severs ties linking them to other human beings. Then exploitation can be rationalized by the in group’s inability or unwillingness to empathize with those they are exploiting.

A healthy, functioning society, McGhee observes, rests on the foundation of a “web of mutuality,” a sense of social solidarity, “a willingness among all involved to share enough with one another to accomplish what no one person can do alone.” That web of mutuality, she convincingly argues, arises from altruistic “good Samaritan” behavior. The World Happiness Report concluded something similar, finding that when people experience altruism, they become more likely to help others, creating a “virtuous spiral.”

As far as I know, I never met Johnson growing up in Centralia, but I encourage him and others like him with crosses displayed in their homes to consider the fact that the teachings of Jesus challenge us to envision new possibilities in our relationships with others, acting in ways that help create a web of mutuality and expanding a virtuous spiral of altruism. In other words, loving our neighbors as ourselves.

As Thurman urges us in quite a few of his sermons, “Let’s try it and see.”

(David B. Gowler is Pierce Chair of Religion at Oxford College of Emory University and senior faculty fellow at Emory’s Center for Ethics. His book “Howard Thurman and the Quest for Community: From Prodigals to Compassionate Samaritans,” will be published in November. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)