(RNS) — When Archdeacon and poet Rachel Mann first read Jane Austen at age 16, she wasn’t exactly a fan.

“I absolutely hated her,” said Mann, who thought Austen’s novels were “frivolous romance stories for very, very posh people.”

But Mann stuck with the novel she was reading — “Emma” — and by the end arrived at a different conclusion.

“I discovered the real Jane, the Jane who is incisive and thoughtful, and whose wit lasered in on the weaknesses of the human condition,” she told Religion News Service in a recent call from her home in Manchester, United Kingdom.

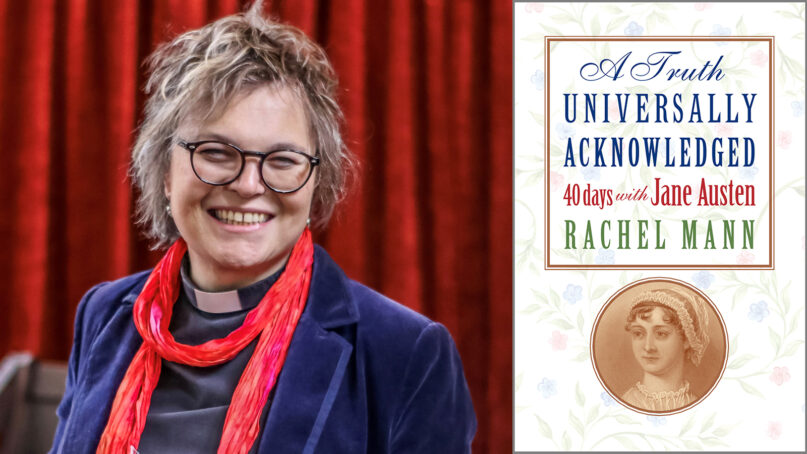

Several decades later, as an archdeacon in the Church of England, Mann said, her appreciation for Austen has only grown. Like the Bible, Austen’s writing speaks to contemporary realities in surprising and liberating ways, she said. Mann’s latest book, “A Truth Universally Acknowledged: 40 Days With Jane Austen,” is a Lenten guide that pairs excerpts from Austen’s six novels with reflections on virtues and vices such as love, greed, humility and, of course, pride and prejudice. RNS spoke to Mann about Austen’s religious background and the lessons her novels hold for the season of penance.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

What makes Jane Austen’s novels fitting for a Lenten devotional?

Lent is about stripping away and getting to a deeper relationship with God. It’s not about giving things up to punish ourselves. Jane Austen is so insightful about human nature. She helps us to get behind the flimflam. She holds up a mirror to our own pretensions and falsehoods as humans. There is a particular power that I think novels have, especially if you’re a quietly moral writer like Jane Austen. We can read about characters like Lizzie Bennet and Mr. Darcy, and the novel shows how they need to grow and develop. It raises questions for us about our own pride and prejudice. Storytelling helps us inhabit these kinds of conversations in ways which are really fruitful.

What do we know about Austen’s experience of and perspective on religion?

Jane was the daughter of a Church of England vicar. She was absolutely surrounded by religion on a daily basis. For Jane, the Christian religion was as natural as breathing. My book includes selections from her prayers, and they reveal the sense in which prayer and worship were part of the warp and the weft of her life. In the late 18th century, early 19th century, in England, there was an evangelical revival. This led to waves of charismatic renewal, and this sense of the Holy Spirit moving. Jane was very suspicious of that. For her, the church was simply part of the fabric of everyday life. And that reflects her social status. In so much of England at that period, particularly the middle and upper classes, it was all about propriety. Showing enthusiasm could show you didn’t belong to the right class of person.

You write that the clergyman Mr. Collins from “Pride and Prejudice” seems to have too little self-respect, while also being pompous. What faith lessons might we draw from Mr. Collins?

Mr. Collins shows us that if we can’t come to trust in who we actually are, then we will become the playthings of others. He ultimately loses his dignity in the face of Lady Catherine de Bourgh by seeking the crumbs from the table of someone who he thinks is better and wiser. There is something about self-respect that is part of the issue with Collins. I don’t mind admitting that there have been times in the influencer-centered age we live in where I’ve had to check myself in my own modest corner of the internet to say, am I in danger of losing my self-respect for chasing crumbs of praise from people I don’t even know? People who don’t respect me?

He reminds us how difficult it is in the culture we live in to have a still and steady center focused on what really matters. That’s what Lent is all about. It’s about saying, let’s get behind the need for charm, or the need to brag and boast, or even from putting ourselves down. In the social media age, we will constantly be tempted to hollow out who we’re called to be and to abandon our vocation to grow into the likeness of Jesus Christ.

What might the marriage between Marianne Dashwood and Colonel Brandon in “Sense and Sensibility” teach us about the quality of God’s love?

What I love about their relationship is the sense of love beyond the beginnings. So much of our discourse around love, both in religion and society, has no sense of that. We tend to think of passion as something that’s on fire, and that’s where Marianne was with Willoughby. We might think of Brandon as second best. But actually, the passion between Brandon and Marianne draws on the notion of being in the hands of each other. Think of Jesus’ passion. One of the meanings of the word passion is about being in the hands of others. It’s not being passive, but it’s being where you are no longer fully in control. That solidity has a greater reality than all the fireworks and all the flames in the world. That’s not something our society or faith sets us up for. I speak as someone who converted from being a very noisy atheist in my mid-20s to Christianity. I had that flame of passion for Jesus. I was so tempted to chase after sensation. But love is about a mutual growing together. It doesn’t exclude passion and excitement, but love is something which abides.

What does Anne Elliot in “Persuasion” teach us about constancy and determination, and what makes these virtues fitting for Lent?

Anne Elliot is 27 at the start of this novel, and she’s considered quite old in the marriage market. She and Captain Wentworth fell in love when she was 19. Yet she was manipulated by her family to say he’s not good enough. But she never, over the ensuing years, loses that love. As she dwells in her regret, she becomes submerged. It’s as if she’s underwater, but the love is being kept alive. And that speaks so deeply into my own Lenten journey. When I look at the world, I have so many reasons to want to panic and become utterly submerged, to retreat physically, psychologically and spiritually. Yet the heart of Anne is hope persevering. And in this frighteningly precarious world, to keep walking through Lent and through life with hope, persevering feels like it’s enough. As we see in “Persuasion,” there are twists and turns. Wentworth has to go through anger and through stages of grief. There are no shortcuts to the third day of resurrection. But there is resurrection — for Anne and for Wentworth. In the midst of how the world looks, there is the promise that Easter will come. That is the heart of Lent. And at the end of “Persuasion,” Wentworth’s declaration of love for Anne is so beautiful because it is a song of experience, not a song of innocence. And it’s shot through with grace and love and resurrection.