(RNS) — The world of Haredi Jews is known for being insular and closed off from the secular world — its adherents focused on a life of devotion to God and tradition.

But the digital age has upset some of those conventions. A growing number of Haredi Jews are embracing technology, and with it, access to the larger world outside.

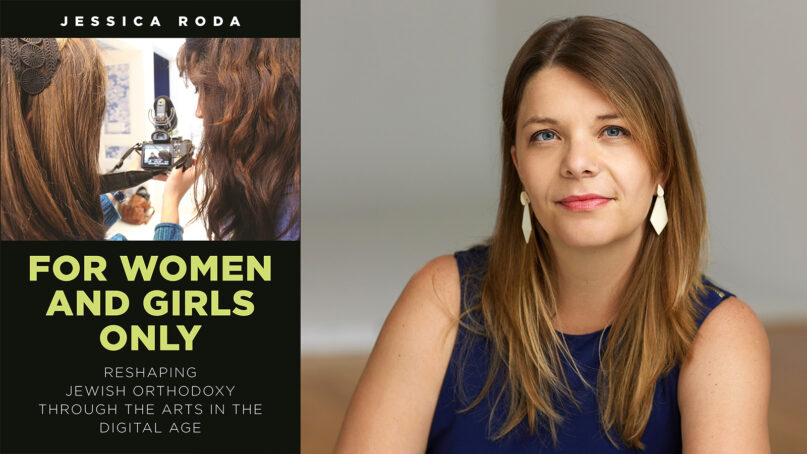

Georgetown University anthropologist and musicologist Jessica Roda has written a new book that explores how women in these Haredi communities across the U.S. and Canada are embracing digital arts to record songs and to produce music videos and full-length feature movies tailored to the gender-segregated world of women.

“For Women and Girls Only: Reshaping Jewish Orthodoxy Through the Arts in the Digital Age,” pries open the world of Haredi women to explore this emerging world of women artists, celebrities and influencers.

Orthodox women are required to dress and act modestly, a rule known as “tznius.” Most married women cover their hair or wear wigs. They must also wear dresses or skirts that cover their knees and elbows.

In addition, they follow a rule called “kol isha” that prohibits men from hearing women sing because women’s voices are considered sexually attractive to men. In effect this means women may not perform in front of mixed-gender audiences.

But within these parameters, Orthodox women have taught themselves how to produce music videos and full-length movies catered specifically for them. This new, alternative art scene often blurs the boundaries between the religious and secular worlds.

Jessica Roda. (Photo by Nadia Zheng)

RNS spoke to Roda about her book and how Haredi women are redefining their roles. (She will also be giving a talk in person and online at 7 p.m., Wednesday, March 6.) The interview was edited for length and clarity.

Tell me a little bit about these Orthodox women who have these home recording studios. When did that start, and what does it look like?

Recording studios started to become extremely cheap in the sense that you can record from your home with your computer and you don’t need very complex equipment. I would say it started in late 2010 for most of the women, and it grew after that. Before that, there may have been some pioneers who had one room dedicated to editing and another room where you will record. Those were the more professional recording studios.

Today some girls will have a computer at home in their bedroom and then she will just record and then these girls will send the material to other women who have a much more advanced professional recording studio to work on the recording and to make it sound better. But you have a lot of different types of recording studios. I’ve been to a home in Montreal of a woman who had a studio in the back of her home, in a playroom. Another example is in New York. This woman has a studio in her basement where she has three spaces, one where she records voice, one where she records the keyboard and other instruments and a place where she will mix the recordings.

How are these musical recordings used?

The girls who are part of this informal market want to record a song for an event, like a birthday, a Bat Mitzvah, an engagement or a wedding. It’s an extremely creative universe for girls and women. They will share it by email, or phone lines where you can also listen to it. They will not put it on YouTube; they will leave it on the informal market. So you cannot find it; you really need to be part of the community to access it.

And there is another one that is also extremely vibrant that exploded during COVID of women who are in the industry. They want to compete with Orthodox male pop singers. These women are also sometimes collaborating with men who have recording studios. They make it available on YouTube and on Spotify, and they label it “for women and girls only.” So these two different types — the informal market and the women who are part of the industry — they dialogue with each other.

What you don’t have is classical music training. That’s very rare. So, the orientation is pop music. And then there’s film, too.

And how is it distributed?

You can buy DVDs in Jewish shops in New York or Montreal or Antwerp or Jerusalem. There is usually a section for women. There’s also some streaming online. The films are usually released around Passover or Sukkot or Hanukkah. You have a woman in charge of organizing those events.

And how do these women get around the extremely restricted internet use?

Well, if it’s income-producing, as part of a business, it’s allowed, though you might have to have a (software) filter installed. The prohibition concerns how Jewish institutions devise strategies to restrict access. However, there’s a dichotomy between the norms and religious authority and the lived reality of the people. While some adhere strictly, others clandestinely or openly break away.

The backlash is more about social media. Orthodox women have an extremely large presence on Instagram, and in 2022 there was a push in many Orthodox circles to get women to disconnect from social media. But none of the women that I’m writing about in my book canceled their accounts — none of them.

What I found is that the women who are using social media, they don’t want to challenge or leave Orthodoxy. They want to reinforce it. They want to make it more vibrant and entertaining and provide role models so girls and women will not need to leave the community.

Watching the videos it’s clear women are informed by popular culture, whether it’s the way they wear makeup, their dance moves or even the camera poses.

Of course. They consume it. And they make it Orthodox. There’s a form of indigenization of celebrity culture.

Is their work derivative?

It’s part of a global culture. If you go to Japan or Argentina or Chile, you will find some similarities, and also some specificity in their music. They adapt it. It’s a translation of celebrity culture.

Do they critique their culture, too?

The women who are part of the industry do. There are songs about abuse and the idea of acceptance of one’s beauty, mental health and depression. Malky Weingarten’s movie “Hush Hush” is about the stigma around mental health. Her first movie, “Mali,” is about autism and disability.

The goal is to reinforce Orthodoxy. But you have some who discuss the challenges they have. Then you also have this industry of artists who left Orthodoxy who offer a clear critique of it, and many, many Orthodox women watch it.

Your book points to a kind of permeability between the religious and secular worlds. How are the borders between them dissolving?

“For Women and Girls Only: Reshaping Jewish Orthodoxy Through the Arts in the Digital Age” by Jessica Roda. (Courtesy image)

It’s really a dialogue between those artists who are inside (the community) and those on the outside. Ideas are circulating and things are always in movement, even if each system functions within its norms. Things are changing, and there’s a lot of contact between those two worlds. You have multiple worlds.

What is the impact of social media on Orthodoxy?

It was resisted initially, and still many don’t have time or patience. When you have nine children and maybe grandchildren, you’re very busy. But others want to be connected, they want to know what’s happening, and they’re consuming it. Even within Satmar, the most conservative Hasidic group, there’s a group of women who have a music band and who perform and who have a studio; they also have a certain (level of) internet access.

Social media also creates a new type of community, a new type of identity, a certain aesthetic, a certain type of lipstick, and a certain type of skirt. It’s a transnational and global community. It exists alongside the very conservative, extremely restrictive sects.