RALEIGH, N.C. (RNS) — In the weeks following the Hamas attack on southern Israel on Oct. 7, those protesting Israel’s reprisal into Gaza blocked a major highway, staged die-ins in front of federal buildings, confronted members of Congress, and shut down Grand Central Station in New York.

Almost all of these demonstrations were led by Jewish organizations, particularly the self-described anti-Zionist organization, Jewish Voice for Peace. Their prominent opposition to the war from the start both challenged Americans’ ideas about Jewish attitudes toward Israel and provoked questions about Zionism.

Jewish Voice for Peace says it is committed to solidarity with Palestinians’ struggle for liberation and opposes Israel’s ongoing oppression of Palestinians.

Pro-Israel Jews have denounced JVP members as antisemitic and not really Jewish. One New York politician called for its members to be excommunicated. Jonathan Greenblatt, CEO of the Anti-Defamation League, said, “These radical far-left groups don’t represent the Jewish community.”

For many U.S. Jews, such denunciations are only stating the obvious: Jews who consider themselves anti-Zionist have long been outside the mainstream.

The term Zionism is variously defined, but anti-Zionists themselves say they oppose Israel’s nationalist ideology that calls for maintenance in the territory of historic Palestine of a Jewish ethno-state, which anti-Zionists say is fundamentally undemocratic. The edges of the debate were sharpened in 2018 when Israel’s parliament passed the Nation State Law, which says that self-determination is “exclusive to the Jewish people” in the land of the ancient Israelites.

A group of Jewish women chain themselves to the fence in front of the White House and call for a cease-fire in the Israel-Hamas war, Monday, Dec. 11, 2023, in Washington. The Jewish Voice for Peace-affiliated activists timed their protest with the White House Hanukkah celebration, which also occurs Monday. (RNS photo/Jack Jenkins)

But increasingly younger U.S. Jews are coming around to the anti-Zionist view. JVP’s ranks have grown significantly in the past five months as Israeli forces have killed more than 30,000 Palestinians, two-thirds of them women and children, leaving the enclave in shambles and its people starving.

JVP, with 24,000 dues-paying members, has doubled the number of U.S. chapters to 80 since Oct. 7., and its email list has grown from 34,000 to over 430,000 in the space of four months. Its North Carolina Triangle chapter, encompassing Raleigh, Durham and Chapel Hill, is one of the largest and most active in the country.

Last month, the Triangle JVP chapter, in coalition with other groups, succeeded in pushing the Durham City Council to pass a resolution supporting an end to the Israel-Hamas war and urging the Biden administration to call for a bilateral cease-fire.

RNS spoke to three of the Triangle group’s 400 activists. All three, who are proudly Jewish and oppose Zionism, campaigned for the Durham resolution and have attended numerous other protests demanding an end to the war.

A new mother confronts the deaths of Palestinian children

Danya Holtzman of Durham, North Carolina, is one of the leaders of the Jewish Voice for Peace’s Triangle chapter. (Photo courtesy Danya Holtzman)

Danya Holtzman and her Israeli-born spouse gave their 11-month-old daughter a Hebrew name and plan to teach her English and Hebrew so she might better understand Jewish rituals and prayers.

But while Holtzman is a proud Jew, the 33-year-old social worker is an equally proud anti-Zionist. After 10 years as a member of JVP’s Triangle chapter, she serves on its leadership team.

Holtzman’s Jewish identity has never been in doubt. Her parents instilled a love for the Jewish tradition of justice, even if they did not have much use for religious observance.

Her bat mitzvah ceremony at age 12 took place not in a synagogue but through a mostly secular alternative for families that want to educate their kids about Jewish culture, history and ethics, rather than religion. The plight of non-Jewish residents of the land was on her mind even on that day when she gave a talk on the biblical story of Abraham, his Egyptian servant Hagar and their son, Ishmael.

At the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Holtzman took a class on the history of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. In 2011, during her junior year, her parents took her and her sister to Israel. In addition to meeting her father’s cousins and friends, the Holtzmans toured the West Bank, visited the settlements, went through the checkpoints and saw the barrier built by Israel along the Green Line — the border demarcating the 1967 border — and parts of the West Bank.

Over the next few years, she came to realize that Israel’s occupation of the Palestinian people was rooted in its Zionist ideology that privileges Jews over non-Jews. “I believe very strongly in the idea of an egalitarian state, the idea that everyone who lives in a place ought to have equal rights, which feels like a pretty basic principle,” she said.

Holtzman joined JVP after the 2014 Gaza War, when Israel invaded Gaza to quell a series of missile strikes by Hamas. When acquaintances asked what she thought of that conflict, she felt it was time to get involved to make it clear not all Jews supported Israel’s actions.

At the time, JVP had launched its eventually successful campaign to get Durham County to end its contract with private security corporation G4S Secure Solutions, which also provided services to the Israeli prison system, which locks up thousands of Palestinians.

Over the years she has participated in protests and celebrated Jewish holidays with fellow activists, but Holtzman said that, as a first-time mother, the current conflict, has been especially terrifying.

“For me as a parent, I hold my daughter when she’s crying and she’s feeling sick, and I think about the babies in Gaza,” Holtzman said. “I’m thinking about the parents there who are feeling helpless to care for their children who are starving to death.”

Untethering Judaism from Zionism

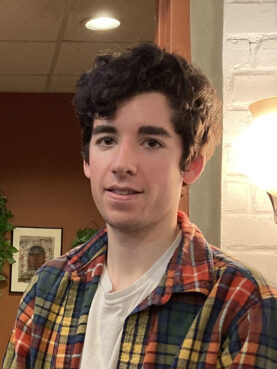

Jacob Ginn is a graduate student at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and a member of the Triangle chapter of Jewish Voice for Peace. (RNS photo/Yonat Shimron)

As a boy studying for his bar mitzvah at a Chicago-area Reform synagogue, Jacob Ginn took note of his congregation’s advocacy and promotion of the State of Israel.

His Sunday school class had the big map of Israel showing what’s sometimes called “Greater Israel,” the West Bank and Gaza. Israeli missionaries, including military officers, would regularly speak to his class about Israel’s accomplishments with the goal of enticing U.S. Jews to visit and make aliyah, or immigrate.

“The temple wanted to instill this idea that Israel is your land and Israel is so great,” said Ginn, a 30-year-old graduate student at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. “That was like a very big part of the Sunday school and general Jewish education that I received.”

Even as a boy, he understood this was propaganda. Soon after his bar mitzvah, he dropped out.

As an undergraduate at the University of Michigan, he was eligible for Birthright Israel, a free, 10-day trip to Israel for young U.S. Jews. But his Lebanese-born roommate had already educated him about Middle East politics and Israel’s role in it. It seemed unfair that Jews could take advantage of such trips yet Palestinians whose ancestors had lived there for generations could not. He declined.

In 2015, he supported Bernie Sanders for president and joined the Democratic Socialists of America’s Chicago group, who introduced him to an anti-Zionist congregation named “Tzedek Chicago.” (“Tzedek” is the Hebrew word for justice.)

Though he never formally joined, he began participating in Friday night services. “To be able to see an example of an alternative way of being Jewish and of relating to Zionism was eye-opening,” he said. “Before that, I was really skeptical that there was even such a thing.”

When he was accepted to pursue a Ph.D. in sociology in Chapel Hill, he didn’t expect to find anything like Tzedek Chicago in the area. But soon after Oct. 7, he felt he needed to do something and joining ranks with JVP seemed like one option.

“The situation is so urgent that I strongly feel that we need to be doing everything that we can to stop the genocide, especially because this is a U.S.-made genocide,” Ginn said.

Last month, he was arrested along with 25 others for feigning a mass death in the street outside the Raleigh office of U.S. Rep. Deborah Ross. He was charged with two misdemeanors.

Ginn blames President Biden for creating the disaster by supplying Israel with weapons and said he would absolutely not vote for him this year, after supporting him in 2020.

Over the past few months, he has been so disturbed by Israel’s assault he began studying it and wrote a paper for one of his classes exploring the history of anti-Zionism.

“I do have a special focus on Israel for many reasons,” Ginn said. “One, because Israel is doing things in my name. They say that they’re doing this for Jewish safety and that implicates me. I firmly disagree. Zionism does not make you safe. Zionism makes the world more dangerous for Jews.”

Overcoming ideological straits

Thirty years ago, when Reut Ben-Yaakov learned that Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin had been assassinated by a Jewish radical for pursuing peace with the Palestinians, her first response was to shout, “Yay!”

An Israeli born into a religious nationalist family in the West Bank settlement of Elkana, she had been brought up on a brand of Zionism that said Jews have a right to establish a presence anywhere in so-called Greater Israel. Rabin was a threat to that vision.

Reut Ben-Yaakov is in her second year as a postdoc at Duke University. She has joined several Jewish Voice for Peace protests. (Photo courtesy Yael Perlov)

But as soon as she let out that celebration of Rabin’s death, Ben-Yaakov, then 14, understood that she had been overtaken by what she called an “ideological overdose.”

From that moment on, she has gradually weaned herself off of Zionism, as well as the traditional observance of Judaism she grew up with. She now lives in Durham, North Carolina, and is in her second year as a postdoc in Hebrew literature at Duke University.

Ben-Yaakov, now 42, experienced profound disappointment with both her parents’ religious nationalism Zionism as well as in secular Israeli society more broadly.

She cast off the religious strictures at her single-sex high school, preferring pants to skirts, and then enlisted in the military, as all secular Israeli Jews do. From there she enrolled at the Hebrew University. She voted uncommitted, or for the left-wing political party Meretz, and finally for the Arab non-Zionist parties of the secular left.

Taking a doctoral degree in Hebrew literature, she moved to Madrid with her partner, an artist with dual Israeli and Spanish citizenship. There, as a minority in a mostly Catholic country, she felt as if she could reclaim a Jewish identity. She has no plans to live again in Israel.

“The tradition of Jewish thought is constructed on being a minority,” Ben-Yaakov said.

On Oct 7., she was teaching “Introduction to Israeli Culture” at Duke. As horrific as the assault was, she knew the reprisal would be even more so. She waited until the semester was over before joining JVP. She calls the Israeli campaign an act of genocide.

“I don’t mean that someone there really wants to kill thousands of Palestinians, but that they just don’t really care,” she said. “The dehumanization is so bad that no one cares.”

Ben-Yaakov prefers to call herself a non-Zionist rather than anti-Zionist. She’s applying for permanent academic positions now in the United States and recognizes that it may not be to her advantage to speak up on these issues. But her Jewish sense of justice compels her to speak out.

“Sometimes I think (Israelis) will all wake up and see what we are doing,” she said. “But no. This is what everyone wants. This is the betrayal. It’s like a historical joke. We were brought up with the question, ‘Why didn’t the world do anything? Why didn’t the world say anything?’ This is the answer. Just like that.”