(RNS) — The 21st century’s most vocal proponent of self-reliance is reportedly suffering from chemical dependence.

Jordan Peterson, the self-help guru best known for his 2018 book “12 Rules for Life: An Antidote to Chaos,” which draws on Jungian archetypes and evolutionary psychology to exhort his (primarily male) readers to embrace the natural, biologically rooted hierarchies of existence, is reportedly in Russia undergoing a cold-turkey withdrawal from an addiction to benzodiazepines.

According to his daughter Mikhaila, who spoke about her father’s condition to Canada’s National Post, the University of Toronto psychologist became chemically dependent upon the drugs (which include common anti-anxiety medications like Xanax) after being prescribed them to deal with the trauma of his wife’s cancer diagnosis.

Peterson’s health problems are, of course, worthy of compassion. But Mikhaila Peterson’s story of brave Russian doctors who were willing to authorize extreme procedures that their more cautious North American colleagues purportedly would not, and her characterization of her father as suffering from physical, not psychological, dependency, is telling.

Peterson’s gospel has always been one of robust masculinism. In his Manichean worldview, there are winners and losers, males and females, alphas and omegas. The primordial binary — the binary of Order versus Chaos — is the root of all social, psychological and cultural existence. All a man needs to be transformed from an unemployed slacker incel into an impressive professional with a clean room and a girlfriend is a Schopenhauerian will and to embrace his primal nature.

Peterson’s ideology has always involved a very particular mixture of valorizing social freedom (you’re on your own, kid) and biologically rooted determinism (but it’s in your DNA). At times, this ideology has manifested itself in unconventional approaches to elements of personal life: Mikhaila herself famously adopted the “Lion Diet” (eating only meat), something her father has also advocated, on the grounds that this reflects man’s natural predatory animalistic state.

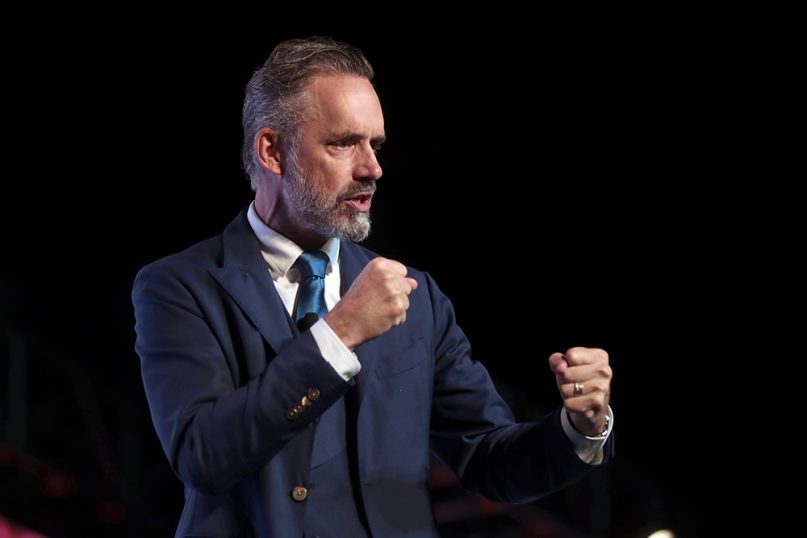

Jordan Peterson addresses the 2018 Student Action Summit in West Palm Beach, Florida, in December 2018. Photo by Gage Skidmore/Creative Commons

And indeed, Peterson himself has frequently characterized people with addiction as weak-willed in his published work. In one of his video lectures on drug addiction, he describes addicts as people who choose such a life because, “You’re just someone bored to death, or somewhat self destructive, or some combination of both.”

Which is what makes the Peterson family’s explanation of his illness susceptible to being analyzed in terms of his self-help themes. The narrative of addiction is at odds with the Petersonianism vision of the self as free (to choose) and not free (when it comes to our biologically driven physical selves). Addiction, after all, is rooted in the understanding of the self as unable to choose freely, even as it depicts the self as determined by a lattice of societal factors.

Mikhaila’s characterization of her father as, essentially, choosing an“extreme” (and implicitly dangerous and transgressive) route for treatment goes some way toward countering a narrative that might otherwise threaten Peterson’s conclusions. “He almost died from what the medical system did to him in the West,” Mikhaila told the press, creating a dichotomy between the brave Russian doctors, who have the willingness and bravery to do what is necessary, and the implicit sissies of Western medicine.

“The doctors here aren’t influenced by the pharmaceutical companies, don’t believe in treating symptoms caused by medications, by adding in more medications and have the guts to medically detox someone from benzodiazepines,” Mikhaila said.

The case of Jordan Peterson, in other words, reveals the problematic limitations of Jordan Peterson’s atavism: Narratives of self-reliance can only hold up, in the face of a medical crisis like addiction, if addiction is cast as a purely corporeal phenomenon. It’s especially convenient if this physical problem is countered with unorthodox and unconventional, “manly” (and risky) treatments that are offered outside the corrupt establishment of the American medical system.

It’s the kind of rugged, transgressive narrative that Peterson himself needs to espouse as part of his personal brand, whether or not it conforms to established medical facts about addiction. It may be dangerous, in other words. But it is, at least, consistent.