Are your first waking moments holy or horrid? Are they animated by morning breath or the breath of God?

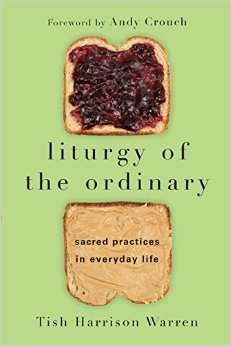

In her book, “Liturgy of the Ordinary: Sacred Practices in Everyday Life,” Tish Harrison Warren says we can’t know God in the abstract, but only in the concrete. So she explores ways to transform your mundane routines into meaningful rituals. The kind of rituals that nurture God’s presence and awaken your spirit to new life. Here we discuss how everything from making your bed to brushing your teeth can help you uncover holy in your midst.

RNS: A lot of my readers are evangelical Protestants or come from low-church traditions. For those readers, can you explain what liturgy is?

THW: James K.A. Smith talks about liturgy as any ritual or practice that connects us to a particular vision of the good life or to the transcendent or sacred. I think that definition is helpful. The term “liturgy” refers to repetitive practices that shape our loves and desires and — often without realizing it — shape who we worship and who are.

When we use the word “liturgy,” we most often mean an order or way of worship on Sundays. All churches have a liturgy. I grew up in a tradition that wouldn’t consider itself “liturgical” but if I stayed home from church on Sunday, I could guess with pretty good accuracy what was happening minute to minute in the service.

But in my book, I also explore the meaning of liturgy beyond the church walls — what the sacred rhythms and shaping practices are in an average day.

RNS: I’m grumpy right after I wake up. How can someone like me see waking as a an opportunity for divine connection?

THW: You don’t have to be annoyingly chipper in the morning. Who you are, the moment you wake up, is beloved. I connect the practice of waking and baptism in the book. I do this because both are gifts of grace we receive and both are beginnings. Waking is a moment to realize that our grumpy (or happy), bad-breathed, messy-haired self is one who, in baptism, has been “marked as Christ’s own forever.” When you wake, you’re given new mercies and a new day, both of which are completely unearned and undeserved, but given again out of sheer grace and abundance.

RNS: How can making the bed become a spiritual practice?

THW: I tell a story in the book about how I never, ever made the bed or even really considered the possibility of doing so. Instead, I woke up and immediately reached for my smartphone and got a morning hit of glowing screens.

One Lent, mostly out of curiosity, I stopped looking at my smartphone when waking and tried to make my bed and sit on it in silence for a few minutes. There was something about making small order out of chaos and touching real sheets and covers and the hard wood beneath my feet — the tangibility of that experience — that shaped my day in subtle ways. For me, making the bed was a tiny practice to submit to boredom, repetition, the quiet, and the tangible over the din and allure of constant infotainment and spectacle.

RNS: Creating a liturgy around brushing one’s teeth will likely seem silly to some readers, why should they take the idea seriously?

THW: The point of my book isn’t to get everyone to sing the doxology or something while brushing your teeth everyday. I’m not trying to get us to randomly insert spiritual gimmicks into a day. I want to say that we probably already have a liturgy around brushing our teeth or waking or going to work or talking to a friend. These activities in our life are rituals that shape us and point to profound meaning about what is good, true, or beautiful.

When we brush our teeth, we are making a statement with our hands and toothbrush that our body is worth caring for. So I ask: Why? Why are these teeth and arms and heart and lungs worth care? Is care for our bodies simply necessary drudgery or is there important truth about our bodies that the gospel bears witness to? And if the latter, what’s brushing our teeth have to do with that?

RNS: Let’s talk about the worst morning: Monday. This is a time when many people want to sleep late. You say that sleeping can be a sacred act. Explain.

THW: In scripture, particularly in the Psalms, sleep is often portrayed as a gift of God and a response to his caretaking of the world. We live in a culture that wants to reject all limitations, even creaturely, bodily limitations. A Sprint commercial declares, “I have the right to be unlimited.” We live as though we ought to have no limits.

But as Christians — and as human beings — we have to learn how to not only submit to our own limits but to embrace them as a way of trusting God and relying on God. The sin in the Garden was marked my humans wanting to be “like God” — limitless and autonomous. And we still so often want that. Sleep is the earthy, embodied way to give up our constant striving to be invincible and to practice resting in God and relishing that we can embrace limits because we trust a God who “does not slumber or sleep.”

RNS: On Mondays mornings the email inbox is overflowing. How can replying to emails become a spiritual action?

THW: I hate email. It is often overwhelming to me. But email is a necessary practice of my work-life and part of the way I honor God in and through my work. On Sundays, Anglicans pray a prayer after Communion that asks God to “send us out to do the work you have given us to do.” That work isn’t just the big picture of our life — we’re asking God to send us out to answer emails, do laundry, or do our taxes too. So I wrestle in the book — and almost every day — about what it means to do these tasks of daily work as one who is beloved of God and sent by him into an ordinary day.