The man who ordained me as a rabbi was Rabbi Alfred Gottschalk. He served as the president of the Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion from 1971 until his retirement in 1996.

Whether it was on the bima of Congregation Emanuel in New York City (which is where I was ordained) or on the bima of Plum Street Temple (which is where Rabbi Frazen was was ordained), or at Hebrew Union College in Jerusalem, at the moment of ordination, he would look each of us in the eye and he would ask each one of us if we were ready for the awesome responsibility of being a rabbi in Israel, a rabbi for the entire Jewish people.

Alfred Gottschalk was not my principle teacher, nor was he my principle influence in the rabbinate. But we had a warm, affectionate, often humor-filled relationship over the years, especially when we would see each other on the streets in Jerusalem or at services there at the college. But in a real sense, he became my teacher. Not in life, but in a story that I first learned about him after he died. I invite you to learn from that story as well.

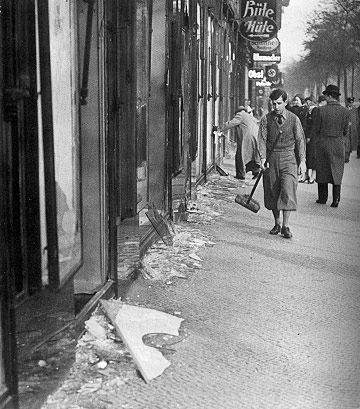

It is a story about Kristallnacht.

On November 9, 1938, eighty years ago this evening — Alfred Gottschalk was barely eight years old. That was Kristallnacht – the “night of broken glass.” That was the night when, all across Germany and Austria, Nazi thugs burned synagogues – among them the most beautiful synagogues in Europe – 267 synagogues in all. They destroyed Jewish homes and approximately 7000 Jewish businesses. 91 Jews were murdered. Many more Jews, crippled by depression and despair, took their own lives. 30,000 Jewish men were taken away and put into concentration camps.

Eighty years ago this evening – it was the beginning of the end for German Jewry, and for European Jewry. It started with boycotts, and restrictions that forbade Jews from serving in various professions, studying in universities, shopping in various stores, having gentiles patronize Jewish businesses….until it was too late.

This is an eyewitness report – of just one small thing that happened on those nights of broken glass. One small scene. This is the face of evil.

The object of the mob’s hate was a hospital for sick Jewish children, many of them cripples. In minutes the windows had been smashed and the doors forced. When we arrived, the swine were forcing the wee children out over the broken glass, bare-footed and wearing nothing but their night-shirts. The nurses, doctors, and attendants were being kicked and beaten by the mob leaders, most of whom were women….

[The eyewitness continues]: I saw a piano in the middle of the street, and a German was playing it. He laughed. “Ha, Ha. It still works. The Jew piano can still play.” [From Leonard Baker, Days of Sorrow and Pain: Leo Baeck and the Berlin Jews]

Rabbi Gottschalk grew up in the tiny German village of Oberwesel. The residents of Oberwesel revered the memory of a young Christian boy named Werner, who allegedly was murdered by Jews in the Middle Ages. In later years, Rabbi Gottschalk would remember that his childhood was essentially peaceful, except for the annual observance of Werner’s Day, when his friends would suddenly turn on him and beat him up, in memory of young Werner whom the Jews had supposedly murdered.

In Oberwesel, it was slightly different. The rabble could not set the synagogue ablaze because it was too close to the homes of so-called “good Germans.”

So the Nazis ransacked it for whatever they could find — and then they tore up the Torah scrolls, and then they tossed the pieces of parchment into a creek.

The next morning, young Alfred Gottschalk and his grandfather waded into the creek. Together, they pulled the saturated pieces of Torah parchment out of the water.

This is what Alfred’s grandfather said to him:

“Some day,” his grandfather told him, “Someday, Alfred, you will put the scroll together again.”

For the rest of his life, Alfred Gottschalk put the pieces of Torah back together again.

The good news, the godly news, the redemptive news: We are of a generation that has both the will and the ability to put the Torah back together again.

Despite the temptation, in the wake of the horror in Pittsburgh, which is a wound to American Jewry and American Judaism that will not heal – to dwell on the pain, and the realization that there are many people in the world, and in America, many people on the far right, and on the far left, who hate the Jewish people – we must be vigilant – in order to protect the safety of Jews.

But we must also be vigilant – to protect the safety of Judaism.

Last Shabbat, the synagogues of America were filled. We came together. We felt the support of the larger community.

But, let us not rely on the external dangers to bolster Jewish life. Such upticks in our consciousness are bound to be short-lived. A people needs a radar – but it also needs a rudder.

Let me conclude as I began – with a memory of Kristallnacht.

Emil Fackenheim was one of the greatest Jewish thinkers of our time. He had been a rabbinical student in Berlin before the war.

In the wake of Kristallnacht, Fackenheim found himself in a prison cell with more than twenty Jewish men. The cell was filled with despair. Then an older man spoke up: “You, Fackenheim! You are a student of Judaism! You know more than the rest of us here. You tell us what Judaism has to say to us now! [From Emil Fackenheim, What is Judaism?]

That is what we ask ourselves: What does Judaism have to say to us now?

And it is to know, to quote the evil piano player: The Jew piano still plays. It still works. It still has sweet and compelling and transformative music to offer to our people, and to the world.

[excerpted from my sermon for this evening at Temple Solel, Hollywood, FL]