PITTSBURGH (USA Today) – The suspicious looks were one thing, but the whispers are what David Hickton remembers from the Sunday mornings two years ago when he would rise from his pew at SS. Simon & Jude to receive Holy Communion.

“I could hear the ‘tsk, tsk, tsk’ while I was going up the aisle,” he says. “Others were muttering, ‘Of all the nerve!'”

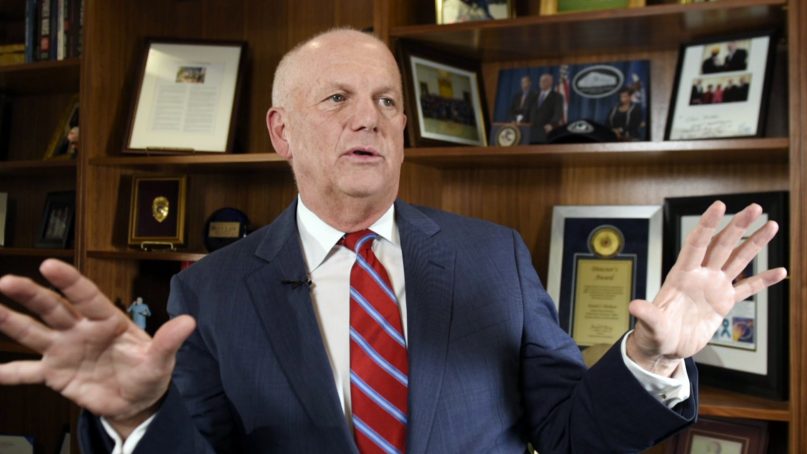

Hickton – then the chief federal prosecutor in western Pennsylvania known for his landmark indictment in 2014 of Chinese military hackers for stealing trade secrets from state institutions such as U.S. Steel – had just revealed his new target: the Catholic Church.

The former altar boy from working-class Castle Shannon put the full weight of the federal government behind an incendiary theory that the Altoona-Johnstown Diocese should be viewed as an interstate criminal enterprise – akin to the Mafia – based on allegations that for years, up to 50 priests had abused hundreds of children.

The inquiry, which cast him as a traitor to some in his own congregation, was resolved far short of a dramatic courtroom confrontation when the federal government and the diocese agreed last year to create an outside panel to guard child safety.

Hickton’s Sunday morning scorning by fellow churchgoers stands as an ugly example of what federal prosecutors in Philadelphia are likely to encounter as they conduct a broader investigation into alleged sexual abuse by Catholic priests throughout Pennsylvania.

After more than a half-dozen state dioceses acknowledged receiving grand jury subpoenas last month as part of the federal inquiry, the powerful U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops confirmed that it, too, was served notice to preserve documents related to alleged rampant abuse. That action signals the government’s review may include the country’s nearly 200 dioceses – the church’s entire U.S. operation.

Federal authorities declined to comment on the basis for their sudden intervention, but they are likely to consider legal actions – including organized crime enforcement measures – that are not bound by “statute of limitation” restrictions that have allowed hundreds of priests to avoid state prosecution for offenses that occurred decades ago.

The Justice Department’s inquiry comes as a wave of abuse allegations have washed over the Catholic Church in Georgia, Louisiana, Michigan, Mississippi, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, Guam and the District of Columbia.

None has been more stunning than the charges contained in a scathing Pennsylvania grand jury report in August, which concluded that the church shielded more than 300 “predator” priests whose victims numbered more than 1,000.

Among those victims: students at Hickton’s own suburban Catholic grade school – St. Anne – where the Rev. Charles Chatt’s alleged abuse spanned years. It was Chatt, according to the grand jury report, who did nothing when allegations surfaced that a basketball coach was sexually abusing young players, including Hickton’s sixth-grade teammates.

“I guess I didn’t know it at the time, but this was ground zero of the clergy sexual abuse scandal,” Hickton says. Though he was not physically abused himself, he says, he regularly witnessed the agony of teammates after they were violated in the school’s locker room.

‘A real breakthrough’

Minnesota attorney Jeff Anderson, whose practice has represented thousands of abuse victims, characterizes the Pennsylvania grand jury report as an “earthquake” that has shaken law enforcement into responding.

“For decades, law enforcement has been reluctant to confront the church because it has been so politically powerful. The federal government’s involvement now represents a real breakthrough. We’ve always felt like this is what needed to happen. People need to understand, the peril is real,” he says.

This month, there was much anticipation the church would finally confront its widening scandal on its own terms. Then the Vatican instructed a meeting of U.S. bishops in Baltimore to delay any action until February.

The surprise intervention by the Vatican, which enraged victims and survivors of clergy abuse, focused attention – and expectations – on the new federal investigation.

“The federal government represents the absolute best chance we have to get to the full truth in this crisis from every state in the country,” says Zach Hiner, executive director of the Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests (SNAP), the largest advocacy group of its kind. “I don’t know if anyone really knows the full scope of the problem and what has to be done, including me. In some ways, the steps the federal government has taken so far may be unprecedented. It gives us hope.”

The driving tour through Hickton’s Castle Shannon neighborhood – once an enclave of coal miners – is, for the most part, a nostalgic romp: a slight climb to the old family home on Orr Drive; past Tony The Barber on Willow Avenue, a favored haunt of comedian Dennis Miller; then on to the Linden Grove dance hall on Route 88, where in the 1960s, guys in leather jackets gathered on weekends to check out the girls or the occasional souped-up Barracuda.

The unimaginable is saved for last.

The interior of St. Anne Catholic Church in Pittsburgh, where the school Hickton attended is attached. Photo by Matthew Sobocinski/USA TODAY

“You see those windows down there?” Hickton asks, pointing to the bottom floor on the backside of St. Anne Catholic School. “That’s where the locker rooms were.”

The dank space, where Hickton’s sixth-grade basketball squad gathered before and after every game, is the place he describes as “a shooting gallery for child predators.”

After every game, the ritual was horrifyingly the same, he says: The coach, overseen by Chatt, would call for a young team member to join him in the shower room. The encounters would vary in length but would almost always end with a visibly distraught child returning to his locker after being fondled and groped by the coach, identified in the grand jury report as “Mr. Giles.”

Some victims shared their experiences at the time, Hickton says. Others stayed mute, their emotions speaking for them.

Hickton says the abuse became so recurrent during the season nearly 50 years ago that some of his young teammates would start trembling with fear as the last minutes ticked off the game clock.

“It was like Russian roulette: Everybody was looking at each other, worried that they might be next,” he says.

Hickton says he never told his parents about the abuse because “I didn’t know what to say.”

“How does a 10- or 11-year-old kid talk about something like that? I remember worrying that some people might be hurt more if I said something. But I do remember encouraging my parents to come to all of my games. I wanted them there. I guess that was my coping mechanism,” he says.

Although he did not speak out at the time, Hickton says there is “no doubt” Chatt was not only aware of the abuse but engaged in illicit activity of his own.

“Everybody knew,” he says.

‘Nobody to protect us’

Hickton’s account to USA TODAY largely tracks a summary of Chatt’s predatory behavior documented in the files of the Catholic Diocese of Pittsburgh. Those files were turned over to the Pennsylvania grand jury, which published its findings in August.

Chatt is one of nearly 100 Pittsburgh-area priests identified in the grand jury report, which says his misconduct spanned decades. The report included a record of Chatt being informed of the basketball coach’s shower room encounters with young players.

“The victim went to Chatt, who was principal of the school, to tell him that … Mr. Giles had been fondling the genitals of many boys on the basketball team,” the grand jury report states in its account of an alleged incident in 1970. “The victim advised that Chatt did nothing about the reported incidents.”

Chatt, living near St. Louis, says in a brief interview with USA TODAY that “not all” of the allegations in the grand report are accurate. He declines to elaborate, except to indicate he has no memory of allegations involving the coach being reported to him at the time.

“No victim ever came to me and said they were abused by him,” Chatt says.

Chatt, who is one of 17 priests named in an abuse claim settled by the Pittsburgh diocese in 2007 for $1.25 million, says he does not know how long Giles worked at the school, nor does he recall his full name. Giles could not be located.

An attorney for the diocese did not respond to written questions about the tenures of Chatt and Giles. The school declined to respond to questions about the two men.