SÃO PAULO (RNS) — On Dec. 16, Indigenous activists from the remote province of Jujuy, in far northwestern Argentina, were preparing to pack up their camp in a public plaza in Buenos Aires, where they had been living since August, when a group of heavily armed men arrived to forcibly remove them.

The dozen or so activists had come to protest a change in Jujuy’s provincial constitution that they say will make it easier for mining companies to extract lithium from the Indigenous community’s land. Their extended stay in Argentina’s capital allowed them to present their case to the Supreme Court, the Congress and the presidential administration before they were forced out.

“There are some mining projects already in progress, and others getting government authorization. We’ll keep resisting them,” said Néstor Jerez, “cacique,” or head man, of the Ocloya people and one of the leaders of the struggle. “They cause serious damage to the environment and are a kind of pillage of Pachamama,” referring to the South American earth goddess.

The Supreme Court and the Congress is expected to respond to the protesters’ demands within 60 days. When the decision comes down, said Jerez, activists will be ready to organize new marches.

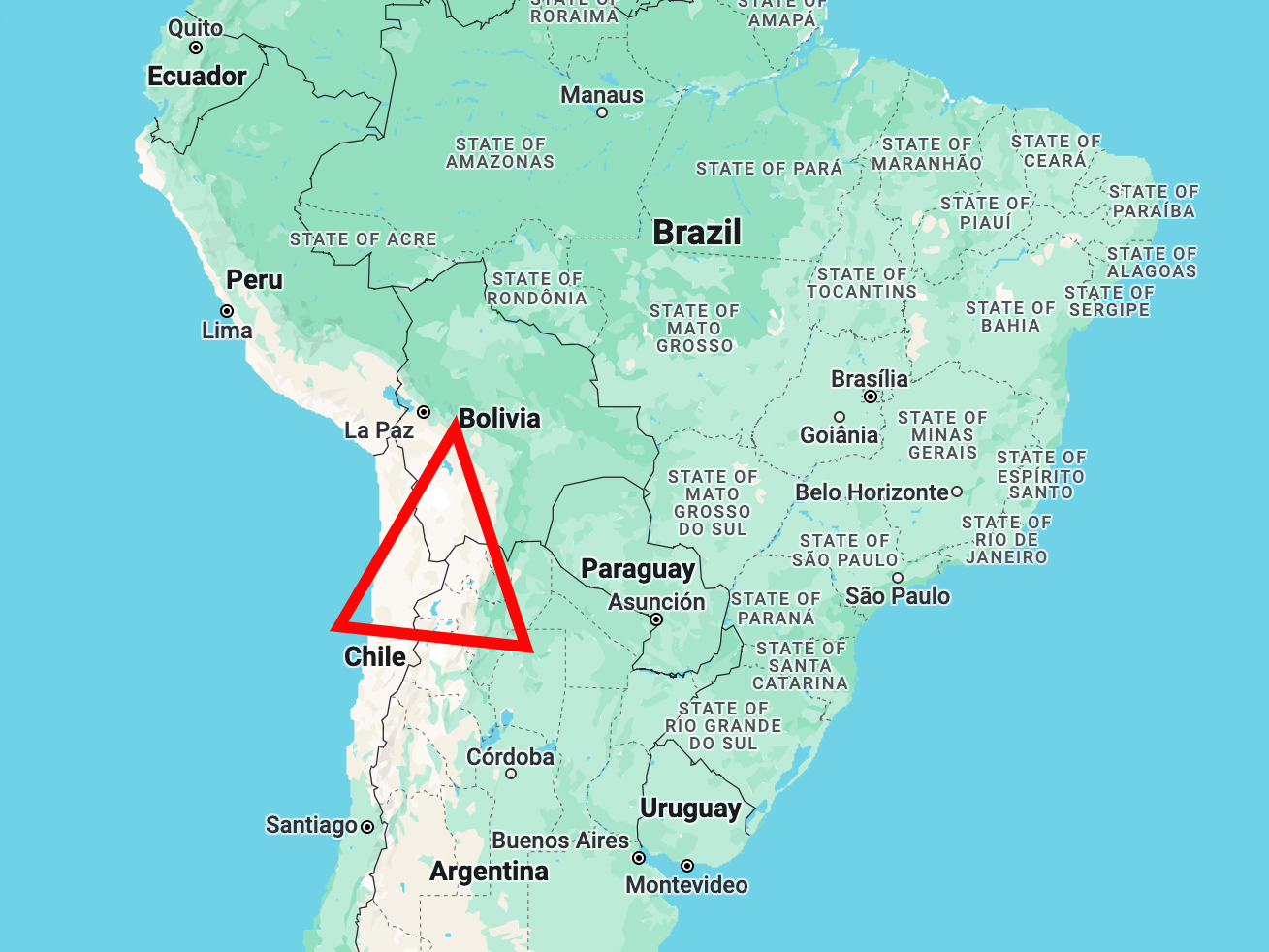

Jujuy is part of the so-called Lithium Triangle, a large swath of the Andes that includes parts of Chile, Bolivia and Argentina that contains huge lithium reserves. Over the past decade, international mining companies have disputed local regulations and property rights, aiming to free up access to the natural lithium deposits found beneath the triangle’s salt flats.

Lithium mining activity at Salinas Grandes salt flats in Jujuy province, Argentina. (Photo by Earthworks/Flickr/Creative Commons)

For the region’s small farmers and cattle ranchers, most of them of Indigenous origin, lithium mining is a multifaceted problem. They have lived in Jujuy and the surrounding area since time immemorial but don’t own the land they work, making it easier for local and national officials to cede the rights to mining endeavors.

Another issue is water, which lithium mining consumes in massive volumes. In the dry climate and scarce water supply of the triangle, mining projects, the growers fear, will deplete irrigation for crops and animals while polluting streams and groundwater.

Not least, the Indigenous population sees lithium extraction as a disruption of their ancient relationship with the mountains that surround their homes, which they hold as sacred.

“For the Andean peoples, mountains have no rank of divinity, but they’re protective beings or locations and for this reason they are sacred. Mountains are also linked to the condors,” affirmed the Rev. Vidal Zerpa, an Indigenous member of the Roman Catholic Church’s National Team of Indigenous Pastoral, an activist organization known by the Spanish acronym Endepa.

Andean peoples over the centuries have held condors in high regard, seeing them as entities that connect the upper world (“Hanan Pacha,” the celestial dimension with the stars, the moon and the gods) with the intermediary or present world (“Kay Pacha,” where humans, animals and the environment dwell). The underworld (“Uku Pacha”) is where the dead and the minerals are located.

Those different worlds can be connected. Caves and other openings in the Earth are said to link to Uku Pacha, for instance. Through ceremonial rites, “people connect to each other and to Pachamama,” Zerpa, who belongs to the Kolla people, explained.

The Lithium Triangle in South America includes parts of Chile, Bolivia and Argentina. (Image courtesy of Google Maps)

“For us in the Andes, everything that exists on our planet has life: people and animals, rocks, mountains, rivers, plants, trees. Nothing is quiet, not even the stars, the noon or the sun,” Zerpa said.

The great lithium projects threaten to create imbalances in that structure.

Among Zerpa’s Kolla, as with many South American religions, faith is shaped by a complex synthesis of traditional cosmology and the Catholicism the Spanish colonizers brought 500 years ago. The Catholic Church and the Indigenous people also come together to fight for the spiritual purity of the land.

“The local prelature of Humahuaca has always accompanied the communities in the struggle for the communal lands’ deeds and in defense of the salt flats,” said Zerpa, referring to the local bishopric. He complains that in more recent years “it has been more distant,” saying that the church failed to express “its prophetic voice in the current resistance.”

Endepa priests and missionaries, however, have been at the forefront of the movement.

The Ocloya’s Néstor Jerez defined the big corporations’ involvement in Jujuy as a “lab experiment of international capital” in which so-called green capitalists are looking for new ways to take hold of traditional populations’ land. “Our life is based on the idea of “buen vivir” (good living). All elements must coexist in balance. We don’t live in the territory, we’re part of it,” Jerez said.

On the other side of the Chilean border, in the Atacama desert, where a number of mining projects are being developed, Indigenous peoples have been divided in their response. On Dec. 7, Cleantech Lithium, a British company, reached an agreement with three Colla communities in the Copiapó region. The following day, the National Colla People Council, along with several other signatories, repudiated the agreement.

“(M)ore than 90% of the Colla People have not been consulted or invited to participate in any way in the decisions that are being made regarding what will be done in the territory that belongs to an entire people,” the council said in a statement.

Tourists visit Salinas Grandes salt flats in Jujuy province, Argentina. A sign in Spanish reads “No to mega mining. Let’s take care of our natural resources.” (Photo by Maggy Idrobo López/Pexels/Creative Commons)

Colla leader Elena Rivera, a member of the National Council’s directors, told Religion News Service that most Indigenous groups in the region don’t want mining. “We know of the damages caused to the environment by lithium exploitation operations. The environmental measures applied here in Chile are favorable to the companies,” she said.

Rivera said that the Colla perform religious ceremonies close to the salt flats and mountains. “In the mountains, there are ‘huacas’ (sanctuaries containing sacred rock sculptures) left by ancestral societies. In regions that may be exploited, close to salt flats, there are centuries-old cemeteries,” she said.

The same pattern has occurred in Brazil, where the Canadian mining company Sigma Lithium has been working on a deposit of lithium estimated to contain 110 million tons in the Valley of Jequitinhonha, a poor area in the northern part of the state of Minas Gerais. Traditional populations such as the “quilombola” communities — descendants of enslaved Africans who fled captivity during slavery — as well as Indigenous groups have been feeling the impact already.

“It’s an area where different biomes are mixed. Deforestation is already noticeable,” said Cleonice Pankararu, a biologist and a member of the Pankararu people.

Her village, where members of the Pankararu and Pataxó peoples live together, is only a few miles from the mining operation’s base. Cleonice said the company has been using water from the nearby rivers to mitigate the dispersion of dust generated by the miners’ blasting.

“But the dust is here. It affects our lungs, especially for children. The explosions cause great vibration and disturb the local fauna. We have been noticing there is a concentration of bats and bees in our territory now,” she described.

The rivers and the mountains of the area are home to the “enchanted” — spiritual entities revered by the Pankararu. The destruction of their environment has saddened many villagers, especially the elders, Cleonice said.

Members of the Pankararu Indigenous people perform the toré ritual, with the “enchanted” wearing the croá-made praiás, or sacred garments, in the state of Minas Gerais, Brazil. (Photo by Eduardo Campos Lima)

Of particular concern is the destruction of the habitat of a flowering plant of the bromeliad family known as croá. The Pankararu ritually collect croá to make the praiá, a sacred garment worn by the “enchanted” during the toré ritual.

In her opinion, the rhetoric concerning energy transition and green economy is simply phony. “We don’t believe in sustainable mining. It doesn’t exist, especially when it comes to lithium,” Cleonice concluded.