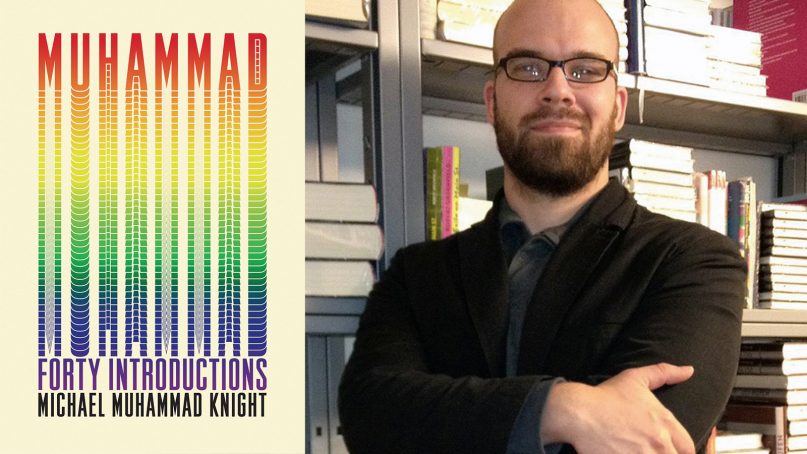

(RNS) – In his new book, “Muhammad: 40 Introductions,” Michael Muhammad Knight gives a crash course in the multiplicity of ways Muslims have historically imagined and remembered the Prophet Muhammad through 40 hadith.

Hadith are the reported sayings of the prophet from many different sources that Muslims look to for guidance in living their faith. Collections of 40 hadith, arbaeen in Arabic, are a genre of exegesis in which Islamic scholars compile selected hadith to offer a particular lens into the life of Muhammad.

Knight’s collection includes hadith that invite explorations of Muhammad’s appearance, family life, infallibility, mystical nature and more. Each chapter is a fresh reminder that for nearly every accepted fact of Islam, there exists another element within the expansive Islamic tradition that competes with, complicates or questions it.

An assistant professor of religious studies at the University of Central Florida in Orlando, Knight wrote the book while planning a seminar about the Prophet Muhammad at Ohio’s Kenyon College. “I don’t know that I always stayed faithful to this, but I started out by imagining the textbook I wanted to see in the world,” he told Religion News Service in a recent interview excerpted below.

The project straddles the lines Knight has followed in his previous 11 books, which include a cult classic novel (“The Taqwacores”), memoir (“Impossible Man”) and nonfiction (“Magic in Islam”). It offers scholarly analysis of the Prophet Muhammad, but with a personal touch. Almost inescapably, writing this book became an act of worship for Knight, who converted to Islam in his teens.

So he leaned in, he said, noting his own reflections on each hadith and including two cycles of prayer — in keeping with the practice of traditional hadith scholars — after finishing each chapter.

Knight discussed the process of creating his own arbaeen and his personal journey with the prophet with RNS. This interview has been edited lightly for length and clarity.

I heard that you’re a new dad. Congratulations! Is there a certain hadith or element of the prophet’s life that you find inspiring as you take on the journey of fatherhood?

Thank you! I don’t sleep a lot these days. There are plenty of hadith about the prophet’s tenderness with kids, particularly the way he would let his grandchildren play on him as he prayed.

There’s the story in which his son died as a baby, and we see the prophet’s tenderness as he cries. For a lot of people, Islam means complete surrender to divine will. It might be confusing, then, to see someone who is so perfect in their surrender weeping as though they are struggling with what was written for them. And the prophet addressed those concerns, explaining that he was given this compassion and love and mercy.

How did you choose which sayings to include? Were there any introductions to the Prophet Muhammad that you had to cut?

“Muhammad: 40 Introductions” by Michael Muhammad Knight. Image courtesy of Counterpoint Press

There were some themes that I knew I had to talk about to use this project as a tool in the classroom. I needed to, for example, explore the prophet’s experience of revelation, the prophet’s marital life, the prophet as a legal authority. Then there were hadith that provoke conversations. There were hadith that were denounced as inauthentic, which still represent something in this tradition, that speak from the margins of the tradition, and can sometimes be fruitfully engaged and seriously considered. These hadith speak to the full range and complexity of the tradition.

How much did you consider the authenticity of hadith when including them? Did you study hadith science?

I don’t take it for granted that pre-modern classical hadith science is actually a science or that it does what it promises to do. The idea is that by assessing the reputation of a given hadith’s transmitters, being able to line them up and say that ‘OK, these two people were both trustworthy and they both lived in the same era and likely met each other,’ we can say that it’s probably a reliable hadith. I think there’s more to the authenticity question than that, but I’m also not an absolute skeptic. I just don’t let the authenticity question dictate what’s useful to me.

Sunni hadith criticism prioritizes the companions of the Prophet Muhammad and is based on the idea that if you can trace the hadith reliably to the companions, then it must be accepted. And that’s a sectarian view. I disagree with the idea that if a hadith goes back to a companion, say Ibn Abbas, then Ibn Abbas must be taken 100 percent at his word. He’s a subjective human being also. The chains of transmission can be a great tool, and they tell a story about texts and how they travel. It tells us something important about the reporters. Historians in other fields say they wish they had something like that.

You talk about how most introductory books, like the Cambridge Companion collection, skip studying the family of the prophet except in sectarian contexts. Can you talk about that and why you found it critical to include?

Historically, everybody loves the family of the prophet, but in modernity that has come to be increasingly sectarian. The Cambridge Companion to Muhammad is a great resource, but there is an unavoidable Sunni-centrism. There are chapters on law, mysticism, the state and the historical context, but there’s nothing about his family. That’s a reminder of the assumption that loving the prophet’s family is only a Shia thing. So I wanted to show how mainstream and popular and significant this is in the tradition, that it is a part of the tradition that is really being erased from Sunni discourses over the past century or so.

Author Michael Muhammad Knight. Photo courtesy of Jonas Yunus Atlas

What other gaps in popular understandings about the prophet were you seeking to fill in?

The mystical Muhammad gets erased, too. In modern conversations we’re looking for an Islamic model of economics and government. We’re asking how the prophet teaches us about gender and ethics. These are secular, worldly concerns — and I don’t take away from any of that. But there’s also a mystical, almost shamanic sort of Muhammad that spooks a lot of people out. Incidents like the experience of the prophet’s ascension to heaven either don’t appear in a lot of modern biographies, or they just get washed away or skimmed over. In a lot of premodern contexts, though, this mystical experience was essential to understanding Muhammad.

We like to think that modernity makes us more open, that it makes things more fluid and malleable, but in a lot of ways modernity also reflects constriction. We’ve really, really limited the kinds of things we can conceivably think about him.

The book is an introduction to the prophet. But for Muslims who already have some understanding of his life, what do you hope they begin to think about?

It can make history a little more complicated. And it can be unsettling, it can be discomforting, it can be threatening in some ways, to think that the narratives we rely on aren’t simply the only narrative. Our narratives are only one of many in a tradition; our personal constructions of Islam today are not the only construction of Islam. That can be destabilizing for a lot of people. But it’s intellectually compelling and personally liberating.

One thing the book might do is encourage Muslims to recognize that their constructions of the prophet are their own, and that the prophet remains malleable and fluid. So they can do this for themselves. They can compile their own Muhammad.

What did you take away as a Muslim from writing the book? And as an academic?

The two are intertwined inescapably for me. I wish they weren’t. But I had to take comfort in the instability. I had to find a way for that instability to nourish me somehow, because academia trains us to take things apart. It trains us to dismantle things, and then it trains us to put them back together. Even if I’m trying to put together my own Muhammad, in a way, I’m still left with this awareness that it’s entirely subjective. It’s entirely a product of my choices and what I have access to. I’m trying to find comfort with myself, as much as with the prophet. The way the prophet emerges from my project is about me.