(RNS) — It began, as so many social justice movements these days do, on Twitter.

Namira Islam, a Bangladeshi-American lawyer living in Detroit, had noticed that many of the ongoing conversations about Muslims online showed ignorance of the faith group’s racial demographics.

Black Muslims were often presumed to be converts or activists. Black Muslims discussing their experiences with racism would receive messages saying that promoting separatism is un-Islamic. Non-Muslims as well as many prominent Muslims seemed to equate the faith with being Arab or South Asian. And the slur “abeed” — Arabic for “slave” — was commonplace.

As Black History Month approached in 2014, she rallied a crew of about 20 activists and scholars to launch a new hashtag: #BeingBlackAndMuslim.

“We wanted to reflect on the erasure of black Muslims in the conversations we were seeing online, as well as in our communities and institutions,” Islam said. “Because those erasures reflect what we’re seeing everywhere else.”

And it resonated. For four hours that Feb. 10 five years ago, the hashtag trended on Twitter not only in the United States, but globally. The responses showcased black Muslims’ pride and joy in their culture and experiences, Islam said, as well as the heartbreak and betrayal they felt at the hands of their brothers and sisters in faith.

Because of the racially egalitarian messages in the Quran and the teachings of the Prophet Muhammad, “people think if you’re Muslim you can’t be racist,” Islam noted. But that couldn’t be further from the truth, she said.

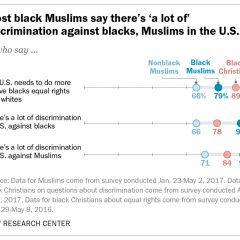

- “Most black Muslims say there’s ‘a lot of’ discrimination against blacks, Muslims in the U.S.” Graphic courtesy of Pew Research Center

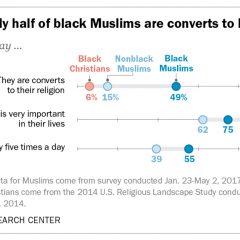

- “Roughly half of black Muslims are converts to Islam.” Graphic courtesy of Pew Research Center

According to the Pew Research Center, black Muslims make up a fifth of U.S. Muslims. While black Muslims are significantly more likely than nonblack Muslims to say that Islam is important to their lives and that they pray five times a day, nonblack Muslims sometimes believe that their black counterparts are not real Muslims. Part of that may be rooted in inaccurate assumptions that most black Muslims belong to the Nation of Islam, which many consider to be heretical. In fact, just 2 percent of black Muslims currently identify with the Nation of Islam, Pew reports.

And while about 92 percent of black Muslims say black people face “a lot” of discrimination, only 66 percent of non-black Muslims agree.![]()

Islam, 31, and educator Margari Aziza Hill, 43, saw in the viral hashtag an opportunity to expand the campaign into a long-term educational resource for Muslims who wanted to teach their own communities about race and religion.

Namira Islam. Courtesy photo

Together, Hill and Islam launched the Muslim Anti-Racism Collaborative, now commonly called MuslimARC. Their mission statement: “Education for liberation.”

Almost immediately, organizations reached out to the pair asking them to lead trainings and consultations about racism within Muslim communities. They hosted a panel at the Islamic Society of North America’s conference that year and were invited to address a group of high school students competing at the annual Muslim Interscholastic Tournament. They were expecting an audience of 25 bored teens. Instead, they found themselves facing a rapt audience of 250.

“So right away we realized this was more than a hashtag,” Hill, MuslimARC’s managing director, said. “These people all thought they were alone in their experiences. So we started to think about how to sustain the conversation, how to intervene in this issue that clearly needed to be discussed.”

Five years since that conversation began, their project has helped to train some of America’s largest Muslim advocacy organizations in racial justice.

Hill — who has a background in curriculum design and has taught at a community college as well as Islamic school and summer camp — had been taking a course on virtual instruction at the online education platform Coursera ahead of #BeingBlackAndMuslim’s launch.

“I had this idea to make anti-racism accessible in the same sort of way,” said Hill. “Because how do you even learn anti-racism if you’re not on a campus or working with a social justice organization? If you’re just a regular lay person, how do you access that?”

Their solution was to develop a set of curricula: for organizations to train their members about racial justice and combating Islamophobia, and for individuals to understand how to be better allies. They produced a toolkit to help Muslims understand how to respond to police brutality and Black Lives Matter — “we must unequivocally affirm the egalitarian nature of Islam in which the Qur’an and Sunnah (Islamic traditions based on the actions of the Prophet Muhammad) clearly condemn racism,” it noted — and hosted or facilitated online courses, webinars and meetups. Ahead of the anniversary of the assassination of Malcolm X, they asked imams around the country to focus their Friday sermons on the shooting and his life.

They also lead workshops and consultations for groups who need guidance in adopting inclusive practices. Their clients and partners have included the Council on American-Islamic Relations, MPower Change, Faith in Action, the Inner-City Muslim Action Network, Take On Hate, the Chicago Regional Organizing for Anti-Racism and Pop Culture Collab, with whom they consulted on the upcoming Sameer Gardezi-directed film series “East of La Brea.”

Margari Aziza Hill. Courtesy photo

Many mainstream Muslim advocacy organizations are now actively working for movements such as Black Lives Matter and pushing for funding more black Muslim grassroots projects, movements they once shied away from.

At an event Feb. 10 celebrating MuslimARC’s five-year anniversary in Los Angeles, Hill told local Muslim leaders “we can trace the lineage of the language that we introduced.” National organizations that were once ruled by “respectability politics and a white aspirational lens,” she said, have now shifted to a “social justice lens.”

Since that first hashtag conversation, MuslimARC says, it has reached more than 20,000 people in more than 40 cities.

That number is multiplied by those who have been impacted by their work, like Islamic studies scholar Kayla Wheeler, who teaches at Michigan’s Grand Valley State University. Wheeler said that a series of interviews Hill and Islam conducted with Muslims of different racial backgrounds, which she found on Twitter, has helped her inform the way she teaches about Latino and Asian Muslims.

#BeingBlackAndMuslim also inspired Wheeler’s 2-year-old Black Islam Syllabus project, in which she is compiling educational resources on black Muslims based on contributions solicited via Twitter.

Wheeler, in turn, has inspired other academics to collect resources, such as the Sudan Syllabus, curated by University of Pennsylvania doctoral student Razan Idris, and the Islamophobia is Racism Syllabus, curated by 10 prominent scholars.

“For me it’s a space to not only see myself recognized but also to challenge my own assumptions about what Islam is and who is involved in Islam,” said Wheeler. “It does a disservice to graduate students when we teach about Islam in a way that is Arab-centric and ahistorical.”

MuslimARC executive director Namira Islam, from left, managing director Margari Aziza Hill and administrative director Hazel Gomez stand outside the site of ARCHouse in Detroit, Michigan. Courtesy photo

Hill and Islam say they want to lead a faith-driven dialogue that disrupts the often-fraught dynamics between non-black and black Muslims. Such tensions are particularly high in Detroit, which has America’s highest percentage of black residents, next door to Dearborn, America’s most Arab city.

The demographics have led to clear tensions, particularly due to Arab-Americans’ entrepreneurial success (which some would call exploitative) with small businesses.

This summer, Hill and Islam plan to open their first brick-and-mortar center, ARCHouse – a largely crowdfunded office and training space near Detroit’s historic Muslim Center mosque, founded in the 1980s under the leadership of Imam W. Deen Mohammed.

The MuslimARC team is aware that the organization’s growth has something to do with the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement and the election of Donald Trump. Terms like “intersectionality” and “microaggression” – once nearly exclusive to academics – are bandied about easily these days.

In some ways, that awareness has made MuslimARC’s work easier, Islam said. “It’s opened up a greater willingness to understand.

“But while anti-racism is trendy now,” she added, “we have to remind folks that there’s long-term work to be done. We have to make sure we’re not so distracted by the crisis response that we don’t focus on the systemic issues that were there under Obama, too.”

The founders of MuslimARC say they are themselves continuing to learn and relearn the meaning of racial justice. Part of that is because they have put together a diverse board that includes black, Latina, Arab and South Asian members, which they say helps expose them to new viewpoints – and puts them in a better position to call out the racism they see.

“I’m not asking people to do anything that I myself have not done,” said Islam.