WASHINGTON (RNS) — For two decades, Arnold Saltzman loved chanting Saturday and festival services at a prominent synagogue in the nation’s capital, using the commanding voice that high school friends once compared to famed tenor Enrico Caruso.

Then, when his voice failed, he had to learn how to listen.

It was a stressful experience, he said, stressful enough to raise a cantor’s blood pressure.

“You’re yearning to interpret the liturgy, and all you can interpret is the silent prayer. That’s very humbling,” said Arnold Saltzman, his voice reduced to a whisper. “Cantors have egos. Even if I wasn’t the biggest ego, I certainly had a lesson in sitting, listening to others.”

Some 15 years ago, Saltzman had no choice but to reinvent himself. He pursued rabbinical ordination and found ways, as a music composer, to find his voice again. In a 2012 Yom Kippur sermon titled “Valley of the Broken Piano Hammers,” which he delivered at one of the three congregations where he was a part-time rabbi, Saltzman spoke about a piano graveyard in New York as a metaphor for a troubling culture where everything is disposable.

“It was unimaginable to me that people could do something like that (destroy pianos),” he told RNS last month in his office at Adas Israel Congregation in Washington, where he is cantor emeritus. “Maybe that’s a metaphor for myself — that with my voice in shambles, I felt I had something to give.”

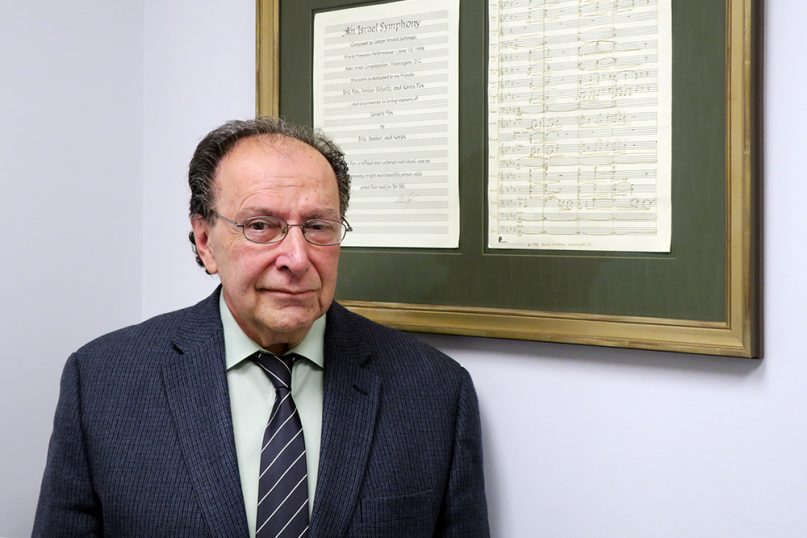

Arnold Saltzman poses in his office in Washington. RNS photo by Menachem Wecker

Saltzman, 70, also talked in a whisper to RNS from the pews at National Presbyterian Church during a dress rehearsal for his latest composition. At the church, some 200 performers, including American University’s orchestra, chorus and chamber singers, the Strathmore Children’s chorus, and soloists Janice Meyerson (mezzo-soprano) and Rob McGinness (baritone), performed a choral symphony that Saltzman composed.

The music was inspired by writings of 12th-century Spanish rabbi, philosopher and poet Judah Halevi, about whom Saltzman learned as an Orthodox yeshiva student growing up in New York in the 1950s and 1960s.

As a child, Saltzman was known as a singer but had little interest in religious instruction. At school, he was prone to fall asleep in religious classes.

Music was a different matter.

Saltzman sang in the Metropolitan Opera children’s chorus for six years and in the Campbell’s soup commercial soundtrack, and he performed with renowned cantors David and Moshe Koussevitzky, Shalom Katz and Moshe Ganchoff, including before 20,000 people at Madison Square Garden. Weddings and bar mitzvahs netted him $50 (the equivalent of $435 today) at the Waldorf, and Sabbath and festival services at Catskills resorts Grossinger’s and Kutsher’s could bring in double that.

Saltzman taught music in New York and then served as cantor at the Conservative congregation Adas Israel for 24 years. In 2002, he contracted a virus that caused dysphonia, a disorder in which muscle spasms affect one’s voice.

“I was able to speak but not sing,” he said.

A year of therapy suggested surgery could restore his singing voice, but the surgery exacerbated matters and had to be reversed. For 10 years, Saltzman was able to speak well and sing a little, but a 2013 car accident worsened his condition to spasmodic dysphonia, which he said has few medical remedies.

“With some medication, I’m good for 30 minutes,” he said in the whisper, which he broke only when he hummed, perfectly, several Hebrew songs.

The Adas Israel Congregation in Washington. RNS photo by Menachem Wecker

With his duties as rabbi and cantor necessarily cut back — he is now the rabbi emeritus at three small synagogues along with being an emeritus cantor at Adas Israel, Saltzman turned his attention to completing his fourth symphony, about Halevi. He had learned about the rabbi and poet as a child, and one story, which he now considers a myth, stood out (although scholars long dismissed this story about Halevi as legendary, new discoveries at the Cairo Genizah suggest that it’s at least possible that the story is true, according to Hillel Halkin, writer, translator and author of a 2010 book on Halevi).

The Spanish rabbi of the story, he was taught, so pined for the Holy Land that he set out at the end of his life to move there. After stopping en route in Egypt, Halevi was murdered within sight of Jerusalem’s walls.

“It was this romantic myth about this poet who had to get to Jerusalem,” Saltzman said. “It was portrayed that you could not be fully Jewish in Spain. You had to go to Jerusalem.”

The line “My heart is in the East, and I am at the edge of the West” is among Halevi’s most famous quotes, and his life was seized upon by lovers of Zion, including Saltzman’s teachers.

“He is really the greatest Jewish poet since David or Solomon,” Saltzman said, evoking the biblical Jewish kings. “This is the best of the best in Hebrew.”

As he studied Halevi, Saltzman came to view him as an early Romantic yet religious poet. Halevi was also a “brilliant improviser,” according to Saltzman.

Despite Halevi’s era being a golden age of poetry, all was not well for Jews at that time.

“People mistake it and think that everything is OK in the golden age. It’s not,” Saltzman said. “In 1066, the entire Jewish community of Granada was wiped out: 4,000 people. That’s nine years before Halevi was born.”

Saltzman inserted part of that trauma into the music, which is all the more poignant for being performed in a church.

“There’s an unease,” he said. “I wanted to create some unease in my music, even if it was beautiful.” He added that music like his can help people of different faiths find common ground and overcome their unease.

Ann Brener, a Hebraic area specialist at the Library of Congress and author of the book “Judah Halevi and His Circle of Hebrew Poets in Granada,” agreed that Halevi was perhaps the greatest Hebrew poet since the Bible.

To understand Halevi’s poems and those of his contemporaries, one needs to set aside contemporary ideas about poetry, according to Brener.

“Today, poetry is just about anything splashed on the side of a bus with enough white space around it and is seen as being intensely subjective and biographical,” she said. “Not so with medieval Arabic poetry, nor with the medieval Hebrew poetry composed in its wake.”

Saltzman wanted the piece to be enjoyable but also “to put people on the edge of their seats.”

“It’s a really dramatic work, which won’t remind them of something else they’ve heard. It’s a knock-your-socks-off piece.”