(RNS) — If you wanted to know about the history of Latinx Pentecostals on the borderlands, you had to talk to Jesse Miranda.

When he agreed to be interviewed for my dissertation over 20 years ago, I approached Miranda with some caution. I thought — wrongly — that he was not going to be open to my critical take on Latinx Pentecostals.

He knew all about the complicated and sometimes troubling history of Latinx converts to Pentecostalism. He had lived through much of it and was willing to share what he knew.

Miranda, who died Friday (July 12), was well known in the Assemblies of God and was the founder of Alianza de Ministerios Evangélicos Nacionales or AMEN, one of the first national leadership organizations for Latinx Protestants in the nation.

When I interviewed him, he was teaching at Azusa Pacific University.

My dissertation was going to take a critical look at the historic role of Latinx in Pentecostalism, focusing on the desire for Latinx converts to lose their ethnic identity as a condition of religious conversion.

It was not going to be a triumphant look at borderlands missions or praise the “great men and women” of the movement. So I wondered if Jesse was going to be open to my line of questioning.

He was. And he wanted to tell his story.

Sitting in his office, I was soon swept up in a history of Latinx Pentecostalism told by a warm, funny, grandfatherly figure who connected the earliest era of U.S. Latinx Pentecostalism with the present day.

For the next couple of hours, Jesse shared his testimonio, his conversion story. It was a great story — since Pentecostal conversion stories are among the best I’ve ever heard. And, of course, as a good Pentecostal, he asked me about my story. Unfortunately, my story was not as exciting.

Jesse was born in Albuquerque, New Mexico, one of five kids born to his father, a lumber mill worker originally from Mexico, and his mother, a New Mexican of Spanish descent. It was his mother’s healing testimony, coupled with the concern that the local Pentecostal church exhibited toward Jesse’s family, that convinced him to convert at age 8.

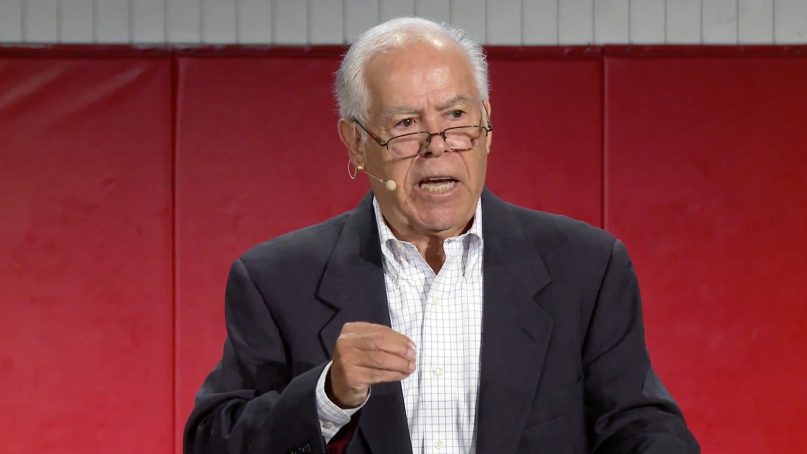

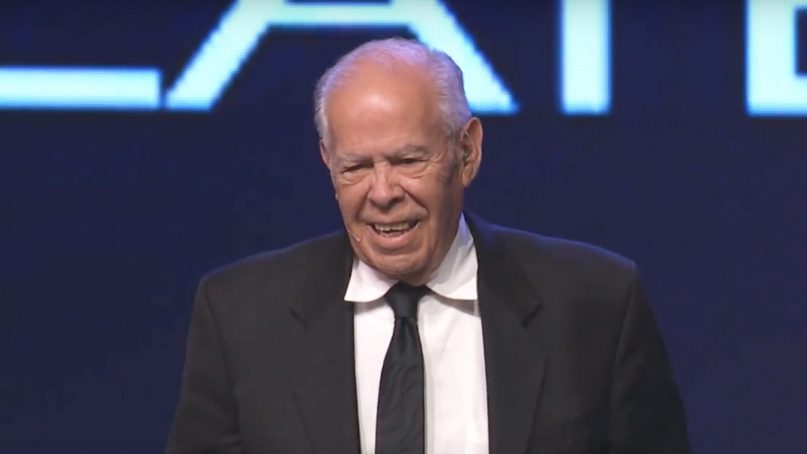

Jesse Miranda preaches in 2018. Video screenshot

Many of the Pentecostal missionaries I was writing about were people that Jesse had met in his early years.

When I found a treasure trove of archival materials at the Latin American Bible Institute, Jesse shared stories of his years teaching there from the late 1950s to the 1970s.

He grew wistful describing the culture of LABI, small town-like, with a deep sense of camaraderie, removed from the ongoing problems of the world. It was a refuge for budding Latinx Pentecostal missionaries and pastors.

He noted how small the school was and how small his community was in general. While I appreciated Jesse’s LABI narrative, I found it too nostalgic, too romanticized.

It couldn’t have been idyllic. After all, he taught there in the 1960s. What about civil rights? Vietnam? The Chicano movement?

In his retelling, most if not all of these historical tidal waves seem to have bypassed LABI entirely. It was this issue, this seemingly cloistered life that most Pentecostals lived throughout this most tumultuous of decades that brought me around to the issue of race and ethnicity.

Jesse and I settled in for a long discussion. He remained quiet and attentive as I mentioned why I wanted to do this project.

The legacy of Latinx Pentecostalism in the borderlands was as much about Latinx being subjected to white supervision as anything else — the vehement anti-Catholicism, the racializing nature of the interactions, the colonial character of it all.

Jesse’s response was that Latinx Pentecostals, because of their small numbers, weren’t in a position to ask their “overseers” for power-sharing.

But, he added, one day, they would.

One day they would reach a critical mass and be able to supervise their own ministry.

Jesse knew his history, he knew a lot about history, but we didn’t always agree. Where I disagree with Jesse was that he held to a “hierarchy of oppression” idea.

This idea holds that African Americans, because of the legacy of slavery, are at the top of the oppression pyramid. I remember disagreeing with Jesse because he believed that Latinx had to wait our turn.

In my view, the solution to the problem of Latinx disempowerment evident in nearly all Pentecostal denominations and organizations was something that needed to be dealt with. There was no need to wait. The political passivity I encountered among Pentecostals was something Jesse could do something about.

He was perfectly poised to effect change.

Jesse’s dream was to found a quasi-civil rights organization akin to the Southern Christian Leadership Conference for Latinx. Such an organization would harness the political power of Latinx Pentecostals and evangelicals along a socially conservative track with exceptions being issues such as immigration.

I remember telling Jesse that this might work, but I also told him that generational change meant that the Latinx Pentecostal youth he taught at LABI, at Fuller and at Vanguard University were not always going to remain the same in their politics.

Jesse and I talked for a while longer, agreeing to disagree on politics and on whether the next generation was going to be as stable and static a population as Jesse seemed to think they would be.

Before I left his office he showed me some of his pictures, the young man at LABI with his Bible, dressed in a suit and tie and ready to go teach. Another picture was of noted Pentecostal missionary Alice E. Luce, who’d co-founded LABI in the 1920s in San Diego.

Jesse tied these pioneering generations together.

Reading page after page of missions reports and articles that often treated Latinx converts with contempt unless and until they had formally converted from “Romanism” had convinced me that Latinx ethnic identity was never going to be secured unless Latinx were able to supervise and lead their own communities.

As a district supervisor for the Assemblies of God in the 1980s, as an executive presbyter for that same denomination, through his last role as a professor of urban and ethnic leadership and director of the Center for Urban Studies and Ethnic Leadership at Vanguard University, Jesse did just that.

He was one of those leaders who, through deft organizational skills and sheer endurance, outlasted the same system that refused to allow another famous Mexican Pentecostal evangelist, Francisco Olazábal, to run his own district in Texas in the 1920s and went so far as to take away his printing press.

Jesse knew Olazábal’s story. Jesse knew the short but complicated history of Latinx converts to Pentecostalism. He told me as I left that, like Brother Olazábal, he knew that no one believed Mexicans and other Latinx Christians were capable of leading their own ministries and their own people.

Jesse spent much of his life proving them wrong.

(Arlene Sanchez-Walsh is a professor of religious studies at Asuza Pacific University and author of “Latino Pentecostal Identity: Evangelical Faith, Self, and Society.” The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily represent those of Religion News Service.)