NEW YORK (RNS) — The morning after an event at Fordham University’s Center on Religion and Culture last week, theologian James K.A. Smith reviewed his against-the-odds attempt at convincing the crowd of the relevance of Augustine, the fourth-century Christian bishop and the subject of Smith’s latest book, “On the Road With Saint Augustine.”

Augustine, Smith said, has something to say to all of us, no matter our age — “Augustine is no respecter of generations,” he told Religion News Service. “There’s nothing new under the sun in a way.” Smith said he is skeptical of generational analysis and reiterated what he told the audience the night before: it’s not just the millennials or “kids these days” who are somehow uniquely a mess.

“I’m not a big fan of this notion that all of a sudden we sort of fell off a cliff,” said Smith. “If anything, I think Augustine calls into question the world the boomers gave us — which so fetishized freedom, autonomy, individuality.”

Freedom, autonomy, individuality. These are the abstract antagonists of Smith’s book — desires easily disordered and all too commonly so in the 21st century.

Smith is a professor of philosophy at Calvin College, but this is not an academic book. Part memoir and part lived theology, it carries Smith’s hopes that people will see Augustine as an appropriate guide for navigating these ills — not because the church father was perfect, but because he experienced and wrestled with them so deeply and personally. Think of him, Smith writes in his preface, “more like an AA sponsor.”

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

What makes Augustine an important voice now?

So it’s this weird mix of: He’s ancient enough to be strange, but he’s perennial enough to feel contemporary. It’s a bit like getting a perspective on our own whacked-out cultural moment. He is such a powerful diagnostician of our tendency to idolize things that will eat us alive. He could help us understand why idolizing political power is not going to give you what you were hoping. Everything we foist our hopes upon is doomed to disappoint us. I think he offers a sort of psychology of some of our disordered hopes in that regard.

Talk about the addiction narrative that you’ve woven into the book.

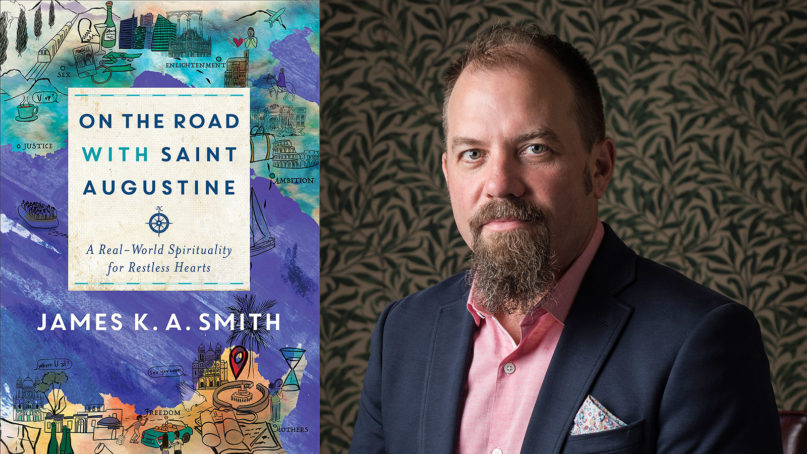

“On the Road With Saint Augustine” by James K.A. Smith. Courtesy image

I teach Augustine’s confessions every semester — for 20 years — and when we get to this climactic narrative where Augustine is trying to take stock of his own inability to become the person he really wants to be, it has struck me that there are ways in which we’ve set freedom up so that almost everything we imagine as freedom turns into addictions. It’s like Augustine sees on the other side of the river the Augustine he’d like to be. It’s like somebody who wakes up and can’t move, this sort of paralysis. Then he looks back and he realizes it was all his own free choices that got him to this place where now he’s locked down and chained in.

The ways you describe the pursuit of freedom, autonomy, individuality — and the dangers in those pursuits — actually sound a lot like the language used in therapy and self-care: finding myself within, finding my truth, releasing baggage. We’ve mostly acknowledged how important counseling can be. But is there some danger there as well?

To be perfectly honest, it was some of my own therapy that got me to a place I could write this book!

But the difference between therapeutic culture as we know it and what Augustine offers us is that I don’t get to make up the story. It’s not me forging a story for myself. It’s me being found in a story that heals, that gives me a sense of “Oh, this is who I was made to be.”

So it’s almost the exact opposite of self-help. And yet it speaks to what I think our cultural self-help is looking for, which is wholeness, healing, fullness, integration, identity.

Much of the narrative of therapy right now focuses on healing from past wounds — be they childhood wounds, church wounds, oppression wounds. That is good work, but can it become too “I-centric”?

Exactly the point. What therapeutic culture is addressing is a perennial human struggle with wounding, right? The difference between the Augustinian prescription and the kind of ‘cult of self-help’ is exactly the difference in what you think the self can do. For Augustine, there is help available, but it’s actually found in coming to the end of yourself and receiving.

Whereas I would say the tendency of a therapeutic culture is it thinks, ‘Oh, we’ve got all the resources we need.’ Augustine thinks if you keep relying on yourself, you are doomed to be continually disappointed. I’m the last person I trust, in a sense. I get that there’s something scandalous in what Augustine is saying to us there. And yet, if it’s true, if that really is the human condition and we are made for someone and something else, then coming to the end of yourself looks like the beginning of healing.

You worry about defining freedom as ‘freedom from” — freedom as a casting off, or as a leaving. But that’s what America is built on, right? The immigrant is often fleeing from something. We have the lone cowboy narrative. Autonomy and self-making are a central part of the American dream. So, are we doomed?

This imagining of freedom as autonomy, independence —”freedom from” — is woven into the very ethos of the American experiment. Augustine thinks that’s sort of doomed to disappointments. It’s ultimately a distortion of who we are made to be. We hold up the idea of the rugged individualist cowboy, yet does that look like a good life? How does that usually work out?

Author James K.A. Smith in 2017. Photo by Seth Thompson

Augustine’s alternative is not conformity and collectivism. He still honors the human need for agency and individuality, but he actually thinks the best way to become the unique self you’re made to be is to find yourself in relation to the creator who made you. And then the community of the people of God who nourish you in your particularities, in your individuality.

So it’s not freedom or conformity, it’s not freedom or collectivism.

I see more and more people who are wondering if that doesn’t feel like a better way to be human. You know this Fleet Foxes song “Helplessness Blues,” right? You know: I’m starting to think that maybe being a cog in some well-functioning machine is actually more meaningful.

I get that. And I think there’s a lot of people who are wondering about that.

How do we balance our need for community, but also make sure people are asking the right questions about their institutions and not just toeing the line? There are some systemic injustices happening — in churches as much as anywhere.

There are some communities worth leaving. Certainly Augustine doesn’t think every community or congregation that calls itself “Christian” deserves the title.

This is where Augustine would say catholicity is one way of expressing what it looks like. You know you are in a Christian community that has room for critique when it doesn’t think it’s the only Christian community, right? When it sees itself as part of a wider web.

It’s intriguing Augustine was the patron saint of the Protestant reformers. I think that those who wanted to reform and renew the church — and who were obviously very critical and whose critique was not received very well — were looking to Augustine as a resource for them to engage in that critical work of reform and renewal.

Among critics of the church right now, across denominations, there are usually two camps: the ‘empty the pews’ camp and then those who are trying to reform. What are Augustine’s words to those who want to reform without burning it down?

I think one of the first things Augustine would say is: Don’t treat your doubts as certainties. That’s when you are ready to burn things down.

Give room for your doubts. I think the danger is swinging to an almost mirror of fundamentalism, where doubts become the thing we are most certain about.

Now, I also think Augustine should engender compassion for people who have experienced trauma and brokenness, such that you want to hear: What are they looking for in that? But he’s going to have worries about fetishizing our doubts. There’s a way in which Augustine thinks the best place to work out doubts is actually in an institution that has room for it.

In some ways, we need the guard rails of showing up for prayer and worship. There’s a stability of God’s presence in the sacraments and you just sort of bring your doubts to the altar. There’s going to be seasons in every Christian pilgrimage where you shouldn’t be surprised to walk in that space. It’s another reason why I think the communal dynamic is so important for Augustine. Some days I show up at church with my doubts and I’m kind of counting on you to sing for me.

Many of our ancient heroes are coming under scrutiny right now. Augustine included, right? Can we question or critique these people who informed so much of our history? Or are we being anachronistic?

As if they enjoyed the historical consciousness that we have.

Right.

I do think to be a faithful inheritor of Augustine is to read him against himself — on women, for example, or sex or whatever it might be.

On the other hand, I do think one of the things that commends Augustine to us is: He’s an old guy, but he’s not an old white guy.

He’s an African, you know, and this is not insignificant. That’s not just a ploy. Once he goes through his adventures in Italy and finally discovers who he is and what he’s called to, he comes back to Africa, he never leaves again. Maybe Augustine is a reminder to us in the Christian tradition of actually how much the European West owes to the heritage of African Christianity. We’ve treated it as if it just came down to us from heaven, when in fact it’s a history of a people. So, in that sense, I think Augustine isn’t just ancient. He’s an ancient African who’s writing from the edge of the empire. Carthage is just nearby and he’s been to the center, but he also knows what it’s like to write from the margins.