(RNS) — Three months ago, the Otis Library in Norwich, Connecticut, held a ceremony to unveil its new memorial to the thousands of Sikhs killed in India 35 years ago in a military campaign and ensuing mass violence.

Then, according to local media, India’s consul general in New York called the library’s executive director to discuss the memorial.

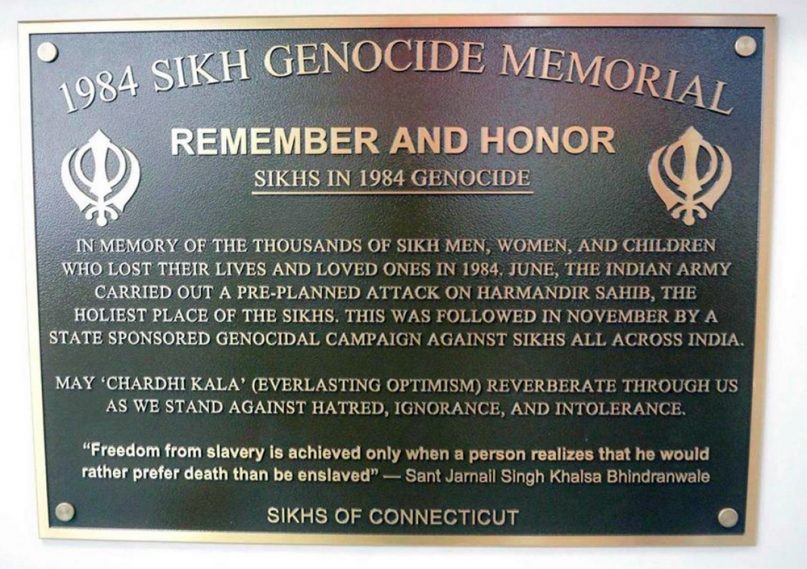

Within weeks, the entire memorial — a Sikh flag, a portrait of a Sikh revolutionary figure and a plaque that honored the 1984 massacre’s Sikh victims while accusing India of committing genocide — was quietly removed from the library.

Sikh community leader Swaranjit Singh Khalsa stands in front of the 1984 Sikh Genocide Memorial at Otis Library in Norwich, Connecticut. The portrait is of controversial Sikh leader Jarnail Singh Khalsa Bhindranwale. Courtesy photo

“The library should be nonpolitical but they made a political decision on pressure of the Indian government,” said Sikh community leader Swaranjit Singh Khalsa, who had donated the 1984 Sikh Genocide Memorial. “So many people have a lot of pain in our hearts and we can’t share our stories. We have no rights, because then we become targeted and we can’t go back to India and see our families.

“It’s sad to see this happening in America,” he said. “Putting American values on stake due to foreign policy is not who we are as America. I don’t know why they feel the need to cater to the Indian Consulate over the real people living in your community for the past so many years.”

The memorial included a plaque in memory of the scores of Sikhs who died in a “pre-planned attack” by the Indian army on Amritsar’s Golden Temple, also known as the Harmandir Sahib and the Darbar Sahib, the holiest gurdwara for the world’s Sikhs.

“As a community space, we welcomed the opportunity and encourage the public to view the memorial and learn more about the Sikh community and its history,” Bob Farwell, the library’s executive director, told a reporter with the Norwich Bulletin before the memorial was debuted.

According to Khalsa, Farwell said in a meeting last month that Sandeep Chakravorty, the consul general of India in New York, called him and threatened the library’s nonprofit status.

Library officials confirmed to the Bulletin that Farwell had received a call from the Indian Consulate before the Otis Library and the Norwich Monuments Committee decided to remove the memorial.

The Consulate General of India did not respond to multiple requests for comment. A library representative said Farwell was on vacation.

Last year, Khalsa sued Chakravorty for defamation when the consul general wrote a letter to Connecticut state Sen. Cathy Osten, who requested that Sikh Genocide Remembrance Day be included in a bill designating commemorative days. In the letter, Chakravorty denied that Sikhs face persecution in India and referred to Khalsa and other local Sikhs’ efforts as “vociferous, pernicious and divisive.”

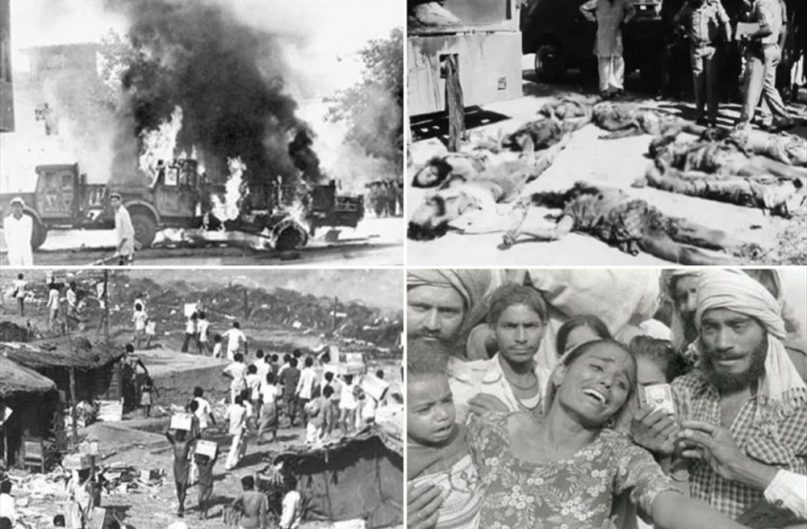

Images from the 1984 anti-Sikh violence in India. Photo courtesy of Creative Commons

Connecticut has a small Sikh community – five gurdwaras and around 400 families, according to Khalsa. But it’s a disproportionately engaged population: Last year, Connecticut became the first U.S. state to recognize the 1984 massacre as a genocide when it passed Senate Bill 489 to name Nov. 30 Sikh Genocide Remembrance Day. The state has also designated June 1 as Sikh Memorial Day and April 14 as National Sikh Day. Khalsa, who received awards from the FBI for his work coordinating the area’s many Sikh awareness campaigns and political engagement initiatives, was also involved in the city of Norwich’s recognition of November as Sikh American Awareness and Appreciation Month.

“What triggered me to raise my voice regarding 1984 is that every time I go to the gurdwara, I saw that there’s a lot of pain among our older generation,” said Khalsa, who works in real estate and owns a local gas station. “When we look at our kids, how are they going to understand what happened if there’s no opportunity to show them?”

The plaque had originally been installed outside of Norwich’s City Hall in 2014. After some local residents allegedly complained over the plaque’s strong wording, the city removed the plaque and put together a monuments committee to consider the request more formally. This year, five years later, the committee approved the memorial and the library agreed to install it.

In mid-September, after the call from the Indian Consulate, the library held a meeting to discuss removing the plaque.

“I hope you are able to understand the depth at which your actions have affected us and what message you are sending to other oppressed minorities and people of color living in Norwich who wish to feel at home living here,” Khalsa wrote in a letter to the library’s board of trustees and monument commission after they removed the memorial. “I was told the memorial would promote diversity and education about the 1984 Sikh genocide and no one would touch the portrait of the Sikh martyr, and now all three things are sitting at my house.”

Carrying their rifles, supporters of Sikh leader Jarnail Singh Khalsa Bhindranwale walk barefoot through the Golden Temple complex in Amritsar, India, on May, 12, 1984. (AP Photo)

The Otis Library has displayed the plaque alongside a Sikh flag, which the library already had on display for about two years. In June, it installed the plaque along with a portrait of the militant Sikh revolutionary Jarnail Singh Khalsa Bhindranwale, who helped lead the Khalistan movement for Sikh statehood.

The plaque also included a quote by the controversial figure, whom many Sikhs consider to be a martyr. Others remember him as a violent separatist.

Two years after Bhindranwale and other armed separatists occupied the Golden Temple, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi ordered a military assault, code-named Operation Blue Star, on the holy site. According to the Indian government, fewer than 500 Sikhs died in the attacks; other counts land closer to 3,000 deaths. Bhindranwale was also killed in the assault, and the gurdwara was badly damaged.

Several months later, on Oct. 31, Gandhi’s Sikh bodyguards assassinated her in revenge. By the next day, frenzied Hindu mobs began setting fire to homes, cars, stores and gurdwaras in Sikh neighborhoods across the country, though the carnage was focused in Delhi. The mobs gang-raped women and clubbed men to death, killing nearly 3,000 Sikhs in the three days of bloody rioting, per official state reports, and leaving thousands more wounded and homeless. Some independent counts have gone as high as 30,000 deaths across India.

The plaque referred to the November massacre as “a state sponsored genocidal campaign against Sikhs all across India.”

The 1984 Sikh Genocide Memorial at Otis Library that has been removed. Courtesy photo

India has refused to recognize the pogroms as a “genocide,” as Sikh leaders have urged the government to do, instead calling them riots. But many human rights activists argue that the government must have been involved in organizing or supporting the widespread anti-Sikh brutality after Gandhi’s assassination. According to several eyewitness accounts, government officials and law enforcement not only turned a blind eye to the attacks, they also directly incited mobs and provided them with weapons.

“The Indian state does a lot of work to make sure its version of the past becomes the only one that is remembered,” said Sheetal Chhabria, a historian of South Asia and associate professor at Connecticut College, pointing to Indian officials’ efforts against a bill passed in Ontario, Canada, to recognize the 1984 attacks as a genocide.

India’s alleged success in suppressing Sikhs’ narrative in Connecticut is “deeply disturbing,” she said.

The divergences in terminology — unorganized riots versus state-sponsored genocide — and death tolls, as well as the sluggish pace of India’s criminal justice system in sentencing officials for their roles in the riots, are major points of tension among the Indian diaspora, explained Chhabria, who teaches a course on India’s contested past.

But the impact of the 1984 massacre goes much deeper than numbers, she noted. Her own grandfather, who was Sikh, became Hindu in the 1980s because of the anti-Sikh climate in India.

“Till today Sikhs in India feel undue pressure to convince others of their loyalty to India by downplaying their Sikh faith,” she said. “Their citizenship and belonging can be questioned far too easily.”

In 2013, the Obama administration declined to recognize the attacks as a genocide after a Sikh-led petition urged the White House to do so, but it noted that there were “grave human rights violations” and “atrocities committed against members of the Sikh community.”

“We came here for our rights, our freedom,” said Kuljit Singh, who lives in the nearby town of Willington, Connecticut, and has worked on various Sikh awareness campaigns with Khalsa. “In India we can’t speak, but in this country we can speak about our religion, our history, about anything. … We want the Sikh Genocide Memorial back, in the library or in City Hall or anywhere. Anywhere that we can show the people what really happened.”

Despite the setback in Norwich, Khalsa said, the city’s Sikh families will remain committed to charhdi kala, the spirit of everlasting optimism referenced on the plaque.

Local Sikhs have begun planning an independent Sikh museum in Connecticut. In the meantime, Khalsa has converted his own basement into a gallery of Sikh art and history that he hopes to open to the public once a month.

“There are so many ways we can shine a light on the truth,” he said. “If we don’t recognize what happened, then we’re destined to repeat it again and again.”