Barbara Brown Taylor, from left, Dr. Eric Baretto and Sarah Bessey have a “living room conversation” after their session on “Evolving Faith & The Wilderness” on Oct. 4, 2019, in Denver. Photo courtesy of Carnefix Photography

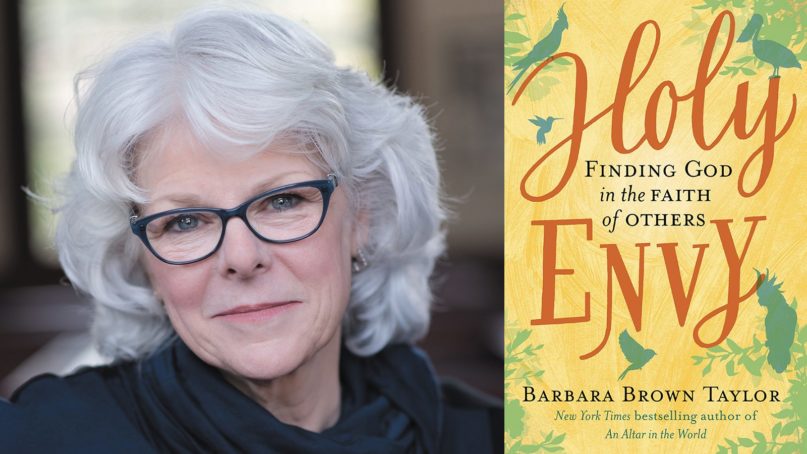

DENVER, Colorado (RNS) — When LifeWay, the research arm of the Southern Baptist Convention, asked American pastors to rank the most influential living Protestant preachers in 2010, only one woman made the list, and only one minister from outside the Baptist fold: in both cases, that was the Rev. Barbara Brown Taylor, an Episcopal priest, teacher and author from Northern Georgia.

Her renown isn’t restricted to the professionals, either. Her 14 books and her preaching have brought her recognition on TIME magazine’s list of its ‘100 Most Influential People in the World’ in 2014. In 2016 she received the President’s Medal at the Chautauqua Institution in New York.

For all her prowess in the pulpit, perhaps her best-known book is her memoir “Leaving Church,” in which Brown Taylor recounts the often-painful, if ultimately redemptive, journey away from pastoring. The book, her first memoir, won her an Author of the Year award from the Georgia Writers Association. Her fourth memoir, “Holy Envy: Finding God in the Faith of Others,” was released in March 2019.

Brown Taylor, a speaker at the recent Evolving Faith conference in Denver, talked with Religion News Service about the event, finding community in the wilderness and the difficulty of deconstructing faith at any age.

RELATED: Evolving Faith conference offers evangelical ‘refugees’ shelter

“It turns out people here are dealing with what a lot of people my age are dealing with, which is a reformation — here, I hear it called a ‘deconstruction’ — of faith. It’s interesting that people in the third part of life are doing the same thing (as) people in the maybe second.”

Author Barbara Brown Taylor. Photo by E. Lane Gresham

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

You made a distinction between reformation or deconstruction in middle age versus “the third part of life.” How are the two ages different?

At this conference, the deconstruction (relates to) a form of evangelical Christianity that people have found toxic. The crowd I travel with, you know, are all old Protestants. They’ve gotten everything they can out of local church efforts and missions and education and they love those places but they’re still hungry. And so their reformation comes out of a different place. The idea is about how much change we can effect in the time we have left. So that’s a difference just based on age. But at the heart of being seekers, that’s a great meeting place across traditional Protestantism, evangelical Christianity — generational crisscross.

Do you think there’s something about this particular moment that has produced this sort of deconstruction or reformation across generational lines?

I think the questions got sanctified. I think those are questions people have had forever, but they weren’t questions (people) felt comfortable asking out loud. Maybe sanctified is the wrong word, but they’ve been authorized. You can ask the questions now.

Phyllis Tickle — of blessed memory — said this is our reformation. It’s our turn. It got called post-Christian for a while. But I don’t believe that. I think it’s post-church. I think it’s post-traditional-structured church because there are too many people, there are 2,500 people here (at Evolving Faith). And you go to Green Belt in England — a whole other continent — there’ll be 10,000 people there.

Do you think Christianity can survive or thrive post-church?

I’m not on social media, but there’s a lot of community being found there. Then this kind of event is a sudden village, you know where the village emerges for the weekend and nourishes itself and then people scatter back. But I get real old-fashioned religious at that point. I really trust the Spirit to keep on blowing. There’s plenty happening and it’s exciting and it’s bringing new voices into the circle. People are mad in all kinds of appropriate ways and getting offended and that seems like we’re doing something right. It seems like fruitful friction, like ‘good Christian friction’ and not the nasty, divisive kind.

I’m hearing two languages being used somewhat interchangeably to describe how people are feeling in this sort of post-church journey — a language of pilgrimage and of wilderness wandering. Are they both accurate in their way?

Pilgrimages, you know where you’re going. You have a destination. I do know people who are redefining pilgrimage as the journey itself and not the destination. It’s (that) corny bumper sticker. You know: it’s all about the journey. It’s all about the ride. So, you’re right, they’re alike.

But, when I pay attention to the Exodus metaphor, people didn’t know. The Promised Land — where the hell is that? You just keep wandering in circles and you say, ‘Haven’t we seen that mountain before?’ That was not a straight-forward pilgrimage, even a straightforward hike. We don’t see the destination. So faith comes into a realm of trust that something new is being formed, but it doesn’t have enough shape yet to aim for it.

So the deconstruction we are talking about is more like a wilderness?

I’m spending my time as a speaker now in these sudden villages, and there are different groups of people, but so much energy and hopefulness. But because I’m an introverted solo-hiker type, wilderness is mostly delicious to me as long as I’ve got some water and something to eat. But the real lost kind? I think there are also people here in the real lost kind. In fact, while I’ve been here, a couple of people (have) come up and sit down and say, ‘I don’t know where to look next or what to do next.’

But this seems to be a great place to be with other people who don’t know what to do next. Isn’t that an interesting way to build community?

RELATED: Barbara Brown Taylor tells Christians to embrace darkness

But then when they go back home, they might feel all the more lonely.

Yeah. And that’s where I become unsatisfied with the technological solutions. You know, I wish people had deeper relationships with the created world, and find some solace and company in non-human relationships or build some kind of local book club, friendship circle. There will be some likeminded people where we all live, but we may have to make an effort.

“Holy Envy: Finding God in the Faith of Others” by Barbara Brown Taylor. Courtesy image

In your new book you write that other faith traditions have something to offer us. For many Christians, it’s alarming to even go there. Why doesn’t it alarm you?

It’s not alarming to contemplatives in any of those traditions. The old word was mystics, (but) I like contemplatives, it’s better. The (non-Christian contemplatives) I met teaching world religions to college students were just happy to welcome us, no alarm. But I knew the alarm would be there if the tables were turned. That seems like part of the Christian self-regard that probably needs to be shaken up. Why would that be a terrible thing? Unless you meant to own the world.

I have friends who are moving forward in that, teachers and writers, they’re out there, (such as) Rami Shapiro and Mirabai Starr. Nadia Bolz Weber is doing that, too — finding the language of wholeness and sacredness in your tradition and finding a way to put that into language that other people can hear.

We have more and more people, particularly those younger than 25, who have grown up completely outside of a religious tradition. They are interested in spirituality, but they are sort of cherry-picking.

I don’t know what to say about those who have grown up in no tradition, who will have to patchwork their spirituality together. Sometimes I use root medicine, because I come from the South. If you are sick, you just find out who knew what plants to eat, which roots to dig to get better. You didn’t really care who showed you where they were. So whatever this new crowd is called — I don’t even like ‘spiritual, but not religious’ and I like ‘nones’ even less — the hunger is real, and in some cases there’s a readiness to make a deep commitment. Writing all that off as shallow is a cheap shot.

I do think there’s a lack of obvious teachers, but how would I know? Podcasts seem to be the new church for a lot of people. Isn’t it interesting how people put together a patchwork of podcasts and those are their wisdom?

Yet there are obvious ways podcasts can’t be church for people, right?

Like flesh and blood and people and bread and wine. Yeah, absolutely. It’s important to make some kind of effort where we live, to make human contact. For me that’s deeply Christian. It’s all about incarnation and the importance of the embodied soul. So, when I’m listening to podcasts, I know there’s an embodied person out there, but I’m not with them in a room. So, it’s limited. It’s of limited comfort.

And the same might be true with these ‘sudden villages’ — people we ‘know’ through social media but only see occasionally at conferences like this.

Yeah, it is. I have a few friends I only talk to two or three times a year. We have continuity, which is more than I have with other people, but it would be a mistake to become fully satisfied with that. I don’t even know if it’s possible to become fully satisfied with that. You’d have to not have many human needs.