(RNS) — It’s been some 700 years since the bubonic plague ravaged central Asia, killing millions of people. A decade or two later, in October 1347, a ship from the Crimea docked in Messina, Sicily. Rats in its hold were infested with fleas that harbored the bacterium that causes the sickness.

That marked the beginning of the era known as the Black Death. Over the next 50 years, it is estimated that at least 25 million people died, between 25% and 60% of Europe’s population.

That disaster is recalled here because of the novel coronavirus, or COVID-19, currently spreading around the world. Not in order to raise great alarm because, at least at this point, it is not warranted. Rather to note, firstly, the stark contrasts between the bubonic plague and the current viral outbreak; secondly, to remind readers of the Jewish angle of the Black Death years; and, thirdly, to convey a lesson from that plague to the current medical challenge.

The contrast lies in several things. For starters, no one at the time of the Black Plague had any idea of what was causing it. At a time of deep ignorance, fueled by Christian lore and superstition, all sorts of theories abounded, none of which did anything to slow the disease. Today, we know what is causing the current pandemic, and, hopefully, modern science can develop the means of protecting the vulnerable from the virus’s worst effects.

And, unlike the bubonic plague, thank God, COVID-19 does not significantly harm the vast majority of those who contract it. It is particularly dangerous to the elderly and infirm, and to smokers and others with less than optimum lung function. But to most people not in any of those categories, the infection results in either no symptoms at all or in flulike experiences – fever, cough and headache.

Finally, as the eminent and wonderfully readable late historian Barbara Tuchman recounted in her book “A Distant Mirror,” the Middle Ages plague brought people to turn on one another rather than work together to deal with the challenge.

Christian religious leaders abandoned their flocks. Parents deserted children; and children, their parents. “Charity,” Tuchman wrote, “was dead.”

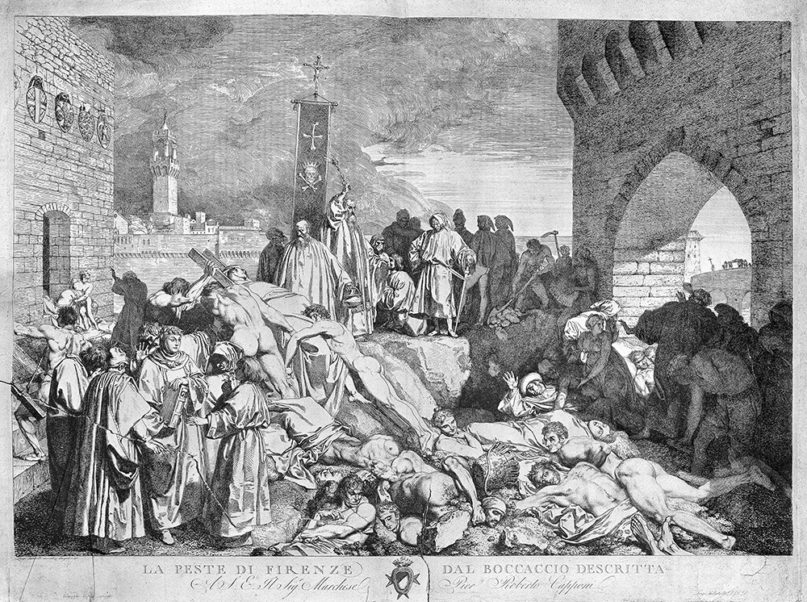

An etching by Luigi Sabatelli of the plague of Florence, Italy, in 1348, as described in Boccaccio’s “Decameron.” Image courtesy of Wellcome Library, London/Creative Commons

Today, nations and scientists and health workers are working hard to educate people about the current virus, to create a vaccine against it and to find the most effective therapies for the stricken, if not an actual cure. People might be quarantined, for their or others’ benefit, but no one is being deserted.

The Jewish angle to the Black Death was the pointing (as usual) of fingers of blame at the forbears of today’s Jews. The plague, it was widely declared, was punishment for Christian society’s allowing Jews to live in its midst as Jews. Jews, too, perished in the plague, only in much smaller numbers, it was said. The resulting “logic” had it that ending the epidemic lay in converting, exiling or murdering Jews. Despite the declarations of several popes that the Jews were not at fault for the plague, people on the street were sure they knew better.

Then the populace came up with a better reason to blame Jews — the stubborn rejecters of Christianity were poisoning the drinking wells of communities, the better to harm Christians. Some Jews even confessed to such crimes — after being forced to do so in order to end their horrific torture.

On Feb. 14, 1349, St. Valentine’s Day, a contemporary observer of events recorded, some 2,000 Jews were forced onto a wooden platform in the Holy Roman Empire city of Strasbourg’s Jewish cemetery and burned to death. Parents held tightly to their children when citizens tried to take them away for baptism.

The Jewish communities in Antwerp and Brussels were exterminated in 1350. From 1349 until about 1390, the Jewish communities of France and Germany were decimated by angry mobs. In 1350, Frankfurt had over 19,000 Jews. By 1400, not a prayer quorum of 10 was left.

Historians tend to take seriously the contention that Jewish communities were less affected by the plague itself, if not from the hatred it unleashed. And that brings us to the lesson to be learned from events seven centuries in the past.

The ostensible reason that the Black Death may have affected Jews to a lesser degree than Christians lies, the historical consensus has it, in the fact that Jews frequently wash their hands.

Upon arising and before morning prayers, and before saying the prayer of gratitude after using the bathroom, and before bread meals (which were most, if not all, meals over most of history), Jews poured water over their hands. And, what’s more, they bathed – a luxury back in the Middle Ages – every week in honor of the Jewish Sabbath.

We Jews still wash our hands a lot. But today most of us live in environments where every doorknob, subway pole and bus passenger is a vector for the transmission of germs.

Although it is likely that the spread of COVID-19 will intensify before it — God willing, soon — abates, we would all do well, especially the elderly and health-compromised among us, to do the equivalent of the Jewish ritual hand-washing throughout the day, ideally, thoroughly and with soap.

That will not only help protect us from the current and other infections, but be a worthy reminder of the even-to-the-death religious devotion of our ancestors in Europe.

(Rabbi Avi Shafran is director of public affairs for Agudath Israel of America, a national Orthodox Jewish organization, and a columnist for Hamodia, in which this article originally appeared. He blogs at rabbishafran.com. The views expressed here do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)