(RNS) — On my bookshelves I have a copy of the famous 1971 “pink” issue of Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought, a pioneering effort for Mormon feminists to make themselves heard. Nearly 50 years later, Dialogue’s latest issue builds upon that effort with a special issue guest edited by the feminist magazine Exponent II.

As a collection of essays, articles, poetry and art all organized around the theme of women claiming power, it’s beautiful and strong. (And downloading it here is free, so please give it a read.) Reading the issue, I was struck by two primary observations. One is exciting, and the other is mildly depressing.

The exciting part is that this is not our grandmothers’ Mormon feminism, or our mothers’, but something bigger. It’s global and interracial.

For example, Brittany Romanello’s opening essay on Latina sisters and the hermandad recognizes that more than 4 in 10 Latter-day Saints around the world identify or have ties with Latinx heritage. In “Multiculturalism as Resistance,” Romanello demonstrates how their voices can be doubly marginalized — they’re women in a church that does not give women much of an institutional voice (see below … ), and they’re Latinas in a church with a prominent Anglo-American culture and a complicated racial history around “Lamanite” heritage.

The spring 2020 issue of “Dialogue,” guest edited by Margaret Olsen Hemming, editor of “Exponent II”

I spoke to Margaret Olsen Hemming, the editor of Exponent II and guest editor of this issue of Dialogue, who said that the commitment to multicultural perspectives is intentional. “I really believe that the most vibrant and important voices in our theology and in Mormon scholarship are coming from the margins of our society and of our church,” she said.

She also wanted the special issue to complicate ideas of who holds power in Mormonism.

In the traditional Western model, women’s exclusion is overt and consistent in The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints: They don’t hold positions in which key decisions are made, they’re not in charge of dispensing money, the callings they’re given are decided on and supervised by men and so on. But one of the gifts of intersectional feminism is to show that this traditional Western model is not the only kind of power, as the issue discusses.

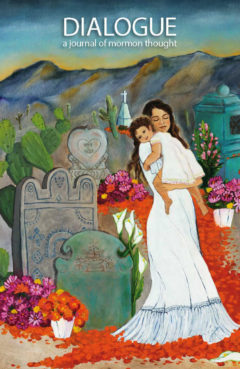

So the good news about the state of “Mo fem,” as it’s called, is that it’s expanding and thriving. It’s including more and different kinds of voices, and it’s challenging dominant narratives from both the right and the left. The whole Dialogue issue reflects that beautiful commitment, including the cover art. The painting by Michelle Franzoni Thorley (top image), called “Family History and Temple Work,” emphasizes women claiming power by holding hands — across history, across cultures — with the temple in the background. There are no individuals in the painting, no one standing alone. If they succeed, they do so together.

I loved the issue. What I found depressing was not the journal itself but my fear that the people who most need to read it won’t ever bother.

I think a lot of that has to do with my own frame of mind right now, heavily influenced by an article last month about important research from Brigham Young University’s political science department. (That’s also a free read: See here.) Basically, the research uncovered abundant evidence of women’s voices being systematically ignored any time a Mormon group is making decisions.

In committees with majority rule, women get fewer opportunities to speak (and thus they learn the lesson that their voices are not important, so they don’t speak unless there are many, many other women there), and they are regularly interrupted when they do speak. Then, because their time in expressing their ideas is so much more limited than male committee members’ time, other committee members devalue their contributions.

It’s a vicious cycle. And it rang totally true to my experiences — sometimes in the workplace, but far more often in church and in LDS culture.

In parts of the church, we’ve progressed to the point where we might have a couple of women present at a meeting at the local level. Go us. But we are nowhere near a place where women will have an equal voice. It’s better than it used to be, but ward councils are numerically stacked so that men will significantly outnumber women. The Handbook stipulates that ward councils should have at least seven men (all three members of the bishopric, the clerk, the executive secretary, and the presidents of the elders quorum and the Sunday school) and the three female presidents of the Relief Society, Young Women and Primary. So that’s a 70-30 distribution.

It’s been interesting to watch how this research has been received on Twitter, as evidenced by political scientist Jessica Preece’s feed:

Her interlocutors’ general approach to their mansplaining seems to be, “Your research can’t be right because I’m a nice guy and I listen to women and don’t discount their voices” — all the while failing to see that they are not listening to women and are openly discounting women’s voices.

I wish I could glue every single one of those men to a chair and force them to read this special issue of Dialogue. Granted, that’s not the most loving expression of cooperative power. Maybe sometimes the traditional hierarchical model can be useful after all.

Related post:

Mormon men are groomed not to listen to women