(RNS) — The ghosts of Hollywood racism marched in Charlottesville, Virginia, in 2017, and again in the past two weeks as much of the country has marched, argued and agonized over the killing of George Floyd.

If you want to see how Hollywood movies and America’s history — especially its history of racism and white supremacy — are linked, watch Spike Lee’s “BlacKkKlansman,” a film I’ve taught often in the past two years. In the course of its two hour and 16 minute run time, Lee’s 2018 movie shows how American movies since “The Birth of a Nation” in 1915 and “Gone With the Wind” in 1939 still resonate in our national conversations on race and prejudice. “BlacKkKlansman” even suggests that, as William Faulkner said, the past is never dead; it’s not even past.

But to help us wrestle with our current moment, it’s worth looking at two films that represent important phases in Hollywood’s depiction of what Jim Wallis has rightly called America’s original sin.

“In the Heat of the Night,” directed by Norman Jewison and the Best Picture winner at the 1968 Oscars, takes some shortcuts in its vision of race and prejudice, but it also works as a strong exploration of race to this day. It’s what we might call a reconciliation film — a story in which a white character learns to be less racist because of his or her interactions with a black character: Think “Driving Miss Daisy” from 1989 or 2018’s “Green Book.”

By tying up a personal racial conflict at movie’s end with a red bow, filmmakers let their audiences off the hook. Look, they say: The white police chief now respects the black detective. Racism is solved!

But in my work on race, film and reconciliation, I argue that it’s important to embrace the life-giving myths of a story, as well as to identify and reject what is soul-killing. Positive movements in personal racism do matter. In the course of the movie, Chief Gillespie, played by Rod Steiger as a typical Southern bigot, goes from viewing a black Northern transplant, Detective Virgil Tibbs, in stereotypical terms to what James Baldwin, in “The Devil Finds Work,” defines as a kind of love.

Sidney Poitier, left, as Detective Virgil Tibbs and Rod Steiger as Chief Gillespie in the 1967 film “In the Heat of the Night.” Photo courtesy of MGM

But the core of this movie is Sidney Poitier’s powerful depiction of Tibbs, and a moment that is as startling a cultural moment as the one in “Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner,” released the same year, when Poitier’s character kisses his white fianceé.

The line that is remembered from “In the Heat of the Night” is Tibbs’ answer to Gillespie’s question about what people in Tibbs’ native Philadelphia call this black detective: “They call me Mister Tibbs.” That is strength and dignity personified. But when Tibbs is slapped by a white man — and then slaps him back — his refusal to bend to white violence was a statement that made the movie radically progressive, at least for 1967.

A step in the right direction — any talk about racism was an improvement when for much of its history Hollywood had ignored people of color as serious characters altogether — “Heat” does more than treat a black man as human. Tibbs is a messianic figure, sent to proclaim a better way to the benighted white people of Sparta, Mississippi. It proposes that interracial friendship can grow when two people begin to see each other as children of God.

But the movie is still an example of well-meaning white filmmakers including people of color in major roles. Lee’s “Do the Right Thing,” which came out in 1989, also deals with racism and law enforcement, but it shows what happens when people of color tell the story. For one, while Poitier’s characters often seemed to be carrying the weighty hopes of an entire race, all the people in Lee’s film are given the freedom to be completely human.

Lee also refuses us the tidy conclusion of “Heat” and leads to more urgent talk about Black Lives Matter, police violence and systemic injustice.

Spike Lee portrays Mookie in “Do the Right Thing.” Courtesy image

The premise of the film is simple: Over the course of one stifling hot day in a majority-minority neighborhood in Brooklyn, the residents argue and sweat and love. Lee’s character, Mookie, is at the heart of the film, a bridge between the Italian American pizzeria owned by Sal (Danny Aiello) and the people of color who make up most of Sal’s customers and most of the community.

Mookie isn’t exquisitely smart or brave, though he does do the “right thing” of the title. The police come, and at their hands a young black man is murdered. The community reacts, just as communities of color and whites of good conscience have done over the past two weeks.

Black and white audiences have argued over that reaction — and over what the film’s message might be — for 30 years. What, we want to know, is the right thing to do about racism in America?

We are asking the same question at this precise moment. It is a gift of this film to suggest that the cycle of violence and oppression we see dramatically portrayed in “Do the Right Thing” has no easy answers, short of all of us becoming part of the solution.

“Are we going to live together?” is the question offered by Samuel L. Jackson’s neighborhood disc jockey at the end of the film. “Together are we going to live?”

If the answer we make to those questions is yes — if our truth is that we seek to see all of God’s children as our relations — then both of these films can inspire conversation and our movement to anti-racism.

Further viewing:

“The Birth of a Nation” (directed by D.W. Griffith, 1915)

“Within Our Gates” (Oscar Micheaux, 1920)

“They Won’t Forget” (Mervyn LeRoy, 1937)

“The Defiant Ones” (Stanley Kramer, 1958)

“Lilies of the Field” (Ralph Nelson, 1963)

“Shaft” (Gordon Parks, 1971)

“Super Fly” (Gordon Parks Jr., 1972)

“Killer of Sheep” (Charles Burnett, 1978)

“Boyz N the Hood” (John Singleton, 1991)

“Twelve Years a Slave” (Steve McQueen, 2013)

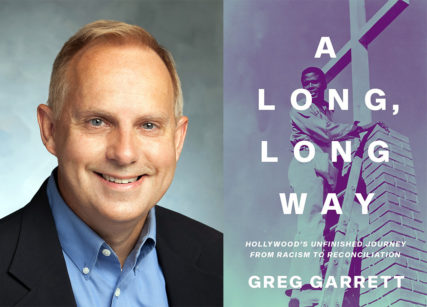

Author Greg Garrett and his book “A Long, Long Way.” Photo by Rick Patrick

“Get Out” (Jordan Peele, 2017)

“Harriet” (Kasi Lemmons, 2019)

(Greg Garrett is professor of English at Baylor University, theologian in residence at the American Cathedral in Paris and author of two dozen books, including the new “A Long, Long Way: Hollywood’s Unfinished Journey from Racism to Reconciliation.” The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)