(RNS) — They just don’t make movies like this anymore.

You know the kind — the ones with casts that contain every A-list actor and actress in the industry.

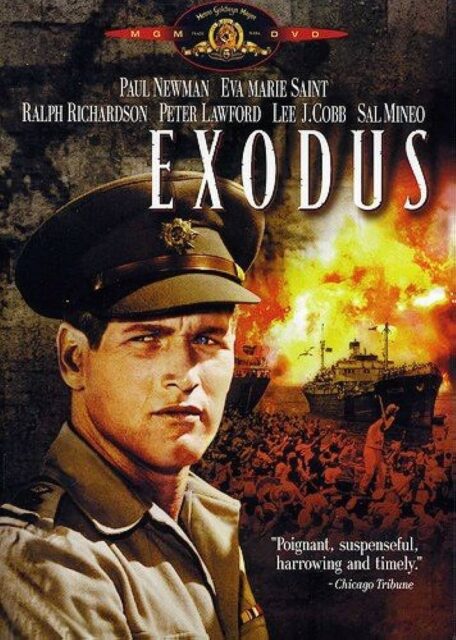

That was the 1960 movie “Exodus,” directed by Otto Preminger. The screenwriter was the blacklisted writer Dalton Trumbo, who based his script on the 1958 blockbuster novel by Leon Uris, which had been the biggest bestseller since “Gone With the Wind.”

Uris’ epic dive into Jewish history crossed the generations, chronicling the emigration to the land of Israel and the struggles that accompanied its creation. In particular, it focused on the voyage of the refugee ship “Exodus,” which defied the British blockade of the land of Israel, and the subsequent creation of the state.

The book was not only iconic; it was redemptive. It was nothing less than a modern Haggadah for a modern Pesach. In the former Soviet Union, refuseniks passed dog-eared copies of the novel around; it served as the inspiration for their own anticipated exodus.

Because I am in Israel, and it is Israel’s 75th birthday, and because recent events have made me wistful for that old heroic image of Israel, I decided to watch the movie again.

So, how does it hold up?

Surprisingly well.

This is why it still matters.

The conversation about Jewish power. The main dramatic tension in the film is the conflict between the two Ben Canaan brothers. Barak, the father of Ari Ben Canaan (Paul Newman, at his blue eyes-est), is a statesman, a moderate. His brother Akiva is a leader of the Irgun, the militant underground force that regularly attacked both British and Arab targets.

The duo was not invented for mere dramatic effect. The tensions were, and are, real — between the Haganah’s policy of restraint and the Irgun’s policy of attack.

As I watched “Exodus,” I reflected on how that sibling rivalry — which ideology will shape the future of the Jewish nation? — is alive and well today.

Consider: The leader of the Irgun was Menachem Begin, who would ultimately serve as prime minister of Israel. His teacher was Vladimir (Zeev) Jabotinsky, the founder of Revisionist Zionism. Jabotinsky’s secretary was the late historian Benzion Netanyahu, father of Benjamin, the current prime minister.

I write this with almost unspeakable pain: Akiva Ben Canaan’s heirs are winning.

The presence of the Holocaust. When the novel and the movie each appeared, the Holocaust had barely appeared in American popular culture; up to that point, only the various popular culture iterations of Anne Frank’s diary had made a mark.

So “Exodus” was a key moment in the American cultural experience of the Holocaust — decades ahead of its time.

First, there is the scene when Karen, the young refugee girl, reunites with her father, who had survived the camps. He is entirely broken and unresponsive. My parents explained that he was “shellshocked” — the only available term for what we now call PTSD.

That scene made an indelible impression upon me; it was the first time that I had encountered anything about the Holocaust.

Second: Dov Landau (Sal Mineo), the young hothead who wants to join the Irgun. The Irgun leaders interrogate him mercilessly on how he survived the camps. He explains that he had been a sonderkommando, responsible for disposing of bodies in the ovens, but there are holes in his story.

Finally, he breaks down and he admits that he had survived because he was a sexual slave in the homosexual brothels of the SS: “They used me like you would use a woman!”

In retrospect, this is remarkable. The conversation about the ovens was decades ahead of its time; no one was talking about that grisly reality.

But, to talk about homosexual rape in the camps? No one was talking about that then; not many more are talking about it now. “Exodus” named the un-nameable.

The meaning of Zionism. The American nurse, Kitty Fremont, takes an immediate liking to Karen. She invites the girl to return to the United States with her, in essence to become a bourgeois American, and to escape the burdens of Jewish history and destiny.

Karen refuses Kitty’s offer. Her place is with her people, and she wants to be a pioneer in the building of the land.

Welcome to Zionism 101.

Where is Judaism in “Exodus?” The short answer: missing in inaction.

With the exception of the mashgiach (supervisor of kashrut) who is checking the meat in the Acre prison, and the traditional shoveling of dirt into a grave, you will see no Jewish religious ritual, though you will see Christian religious processions.

The only name of God that you will hear is Allah, referred to respectfully by Barak Ben Canaan, and invoked by the muezzin in Akko; Elohim doesn’t get a shoutout.

So, where, exactly, was Judaism? It has vanished. In that sense, “Exodus” understood Zionism all too well. The new Jew is the secular Zionist.

The relations between Jews and Arabs. The first dramatic pairing in the film was the two Ben Canaan brothers. The second was Taha, the mukhtar of Abu Yesha, the Arab village that is adjacent to the moshav of Gan Dafna and Ari’s boyhood friend, and the grand mufti of Jerusalem, Haj Amin Al-Husayni (sometimes, Husseini).

The grand mufti represents the nightmare. He was the chief Muslim religious authority of Jerusalem from 1921 to 1937, during the time of the British Mandate. As such, he was the undisputed leader of the Palestinian Arab community, and he was as close to pure evil as the past century has produced. (See the excellent biography, “Icon of Evil: Hitler’s Mufti and the Rise of Radical Islam.”)

The Nazi in the film says that the grand mufti “was our guest in Berlin during the war.” That is true. Al-Husayni was a Nazi sympathizer and a virulent Jew-hater. He had trained an elite corps of Bosnian Muslims for the SS, planning to exterminate the Jews of Palestine.

The grand mufti represents the nightmare. His militant Islam still exists.

Taha represents the dream — of Arab-Jewish cooperation.

That was not a fantasy. The story of Arab cooperation with Zionism is underappreciated. As Hillel Cohen writes in ”Army of Shadows: Palestinian Collaboration With Zionism, 1917-1948,” there were many stories of local Arabs inviting Jewish immigrants to purchase land. My Israeli friends who grew up in Haifa and Akko speak of their grandparents’ warm friendships with Arab families in the 1940s.

As the state of Israel is declared, Taha declares to Ari: “You have won your freedom and I have lost mine.”

Ari refuses to see this as a zero sum game. He begs Taha and his people to stay on as residents of the new state — to become Israeli Arabs — that we “work together as equals in the free state of Israel.” Ari sees the promise in Israel’s Declaration of Independence — that Israel would be both a Jewish stateֶ and “a state of all its citizens.”

That tension — Jewish state, or a state of all its citizens — is still raging today.

Then comes the scene that ranks with the most horrific of my childhood cinematic memories. The mufti’s forces cannot abide Taha’s warm relationship with the Jews. They destroy the Arab village. They hang Taha, daubing his body with Stars of David.

As the film ends, Ari says over the joint grave that receives the bodies of both Taha and Karen, who has been killed by an Arab fighter: “I swear on the bodies of these two people that the day will come when Arab and Jew will share in a peaceful life in this land that they have always shared in death.”

”Exodus” forces me, and all of us, to demand that Ari’s prayer be more than a prayer.

It is not too late, but the clock is ticking.