(RNS) — Confused, dismayed, misunderstood. Young evangelical Joe Biden voters are searching for ways to talk with their friends and relatives about their political decision — and their aversion to President Donald Trump.

Sarah “Rye” Ryan, 31, said she saw the hypocrisy of evangelical leaders for the first time due to Trump’s election in 2016. “It felt like the veil was lifted. … They weren’t to be trusted.”

Ryan’s sister was working for immigrant rights in Boston in 2016 and had similar feelings. She was “so terrified,” Ryan explained, because she was working with immigrants directly affected by Trump’s policies.

Ryan’s sister had a background as a missionary and in theological studies, and Ryan recalled her sister’s confusion around the evangelical backing for Trump. “Trump’s immigration policies are so obviously not what the Christian faith stands for,” Ryan said.

In the last four years, Ryan said she has heard similar stories from other friends in their 20s or 30s — many of whom left the church over what they felt was the hypocrisy of supporting Trump.

Before Trump, these young Christians may have worried they would disappoint their parents if they didn’t go to church, but after their parents voted for Trump, their reaction was more like “no, you’re wrong, and you’ve let us down,” Ryan explained.

In this Sept. 1, 2017, file photo, religious leaders pray with President Donald Trump after he signed a proclamation for a national day of prayer to occur on Sept. 3, 2017, in the Oval Office of the White House in Washington. (AP Photo/Evan Vucci, File)

“It’s quite the sore area,” said Louie Guan, 26. He said he doesn’t even discuss politics with his parents anymore; there’s just too much tension.

Guan moved back into his parents’ New Jersey home due to the pandemic and while he attends New York University for his master’s degree. Moving back “definitely accentuated a lot of these issues,” he said. They watched the presidential debates in separate rooms to avoid any political arguments.

The couple of times they’ve tried broaching the subject of politics, Guan said, they were “coming from such different places.” There was “division over what the facts even are on any singular issue.”

Guan has the added burden of cultural and language barriers. His parents, strong Trump supporters, were born and raised in China. Guan, who voted for Biden, was born in the U.S. While he speaks Mandarin Chinese fluently, it’s not his native tongue and he said he has difficulty explaining complex political issues.

Zak McGaugh, 21, a University of California-Davis senior and a conservative Democrat, said he hasn’t dealt with those same family challenges personally but he is all too aware they exist for many of his peers. McGaugh has been working with the Biden campaign to help turn out young evangelicals like himself.

The group, Young Believers for Biden, uses evangelical language but in a broad way to reach nonevangelicals as well. McGaugh’s particular focus has been making the case for Biden among “center right” young evangelicals.

“That’s where my heart is at,” McGaugh said. “My work has been getting the next generation of evangelicals. … Making a case to them: why they can commit the unpardonable evangelical sin of voting Democrat in this election.”

One of his events, for instance, was speaking with students at Liberty University in Virginia, the second-largest evangelical school in the nation. Until recently, Liberty was led by Trump supporter Jerry Falwell Jr.

McGaugh said his parents were among “the generation of young evangelicals” who voted for George W. Bush and then switched to Barack Obama. McGaugh has some family members, friends and housemates who are Trump supporters and others who are far left liberals. While they sometimes have “lively” conversations, McGaugh said he feels fortunate to have a family where the Thanksgiving dinners are relatively peaceful.

“We definitely clash, but it’s all in good faith,” McGaugh said. “And I know their heart is in a good place as well in their vote, but we definitely have disagreement.”

All three of those interviewed were raised in an evangelical church tradition but said they now have difficulty identifying as an evangelical, given how the term has become associated with Trump and political conservatism.

“I’ve been kind of grappling with the term (evangelical) in the last couple of years,” Guan said. “It seems to have been captured in a very strongly cultural context. And so it’s hard to say I identify with that term too much anymore.”

McGaugh said he’s “unapologetically, theologically evangelical,” but he doesn’t use the term often. “It’s so loaded,” he said.

Ryan grew up in an evangelical church where her father was the pastor. Even though her parents didn’t vote for Trump in 2016 and she had just graduated from an evangelical seminary with a master’s in theology, Trump’s election left her deeply disillusioned with evangelicalism.

Eventually, she left the church altogether. “It was my faith community who … voted Donald Trump into the presidency,” Ryan explained in a video for New Moral Majority, an independent political action committee working on faith outreach in support of Biden.

The young evangelical vote

The young adult vote in general may be a significant factor in the race. Tufts University’s Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement found that, as of Monday (Nov. 2), 10 million early votes had already been cast by 18- to 29-year-olds. In Texas, which had the largest young adult turnout so far, 1.36 million youth votes have been cast, already more than the 1.22 million total Texas young adults who voted in 2016.

According to the results of a Pew Research Center survey provided to Religion News Service and conducted Sept. 30-Oct. 5, there was an age divide among Christian voters in the presidential election. Among 18- to 49-year-old Christians, 47% said they planned to vote for Trump and 45% for Biden. But for Christians 50 and older, support for Trump goes up to 54%, while 43% said they planned to vote for Biden. (The younger age group could not be broken down further, such as 18-29, due to small sample sizes.)

People raise their hands during a worship service in Orange, California. Photo by Edward Cisneros/Unsplash/Creative Commons

Even among white evangelical voters — who broke strongly for Trump in 2016 — there are signs of a widening divide between generations. Young white evangelicals were slightly less enthusiastic about Trump in 2016 than their older peers (78.1% of 18- to 35-year-old white evangelicals voted for Trump, compared with 81.9% of those 36 and older), and that sentiment appears to have grown in the four years since, a trend that first became apparent in the 2018 midterm elections.

In a December 2019 RNS article, political scientist Ryan Burge found evidence of a degrading support for Republicans among younger evangelicals: In 2018, 71.3% of young white evangelicals voted for Republicans (compared with 79.7% for older white evangelicals).

And according to the recent Pew survey, 74% of younger white evangelicals (ages 18-49) intended to vote for Trump compared with 80% of white evangelicals 50 and up.

White Catholics showed a bigger age divide. Fifty-five percent of those age 50 and up said they planned to vote for Trump, but for white Catholics between 18 and 49, 48% support Biden and 44% support Trump.

In the 2019 book “Rock of Ages: Subcultural Religious Identity and Public Opinion Among Evangelicals,” political scientist Jeremiah J. Castle found that young evangelicals are about as conservative as older evangelicals, with some important exceptions. Younger ones are more liberal on three issues: same-sex marriage, immigration and welfare spending.

Burge also found young evangelicals more liberal than older ones on immigration, health insurance, and race and gender inequality. Abortion, however, remains one of the key issues keeping them away from Democrats.

Burge found that young evangelicals are almost as conservative as older evangelicals on abortion, while Castle concluded that young evangelicals may be even more conservative than older ones on that issue.

McGaugh, who opposes abortion, was disappointed when Biden reversed his long-held support of the Hyde Amendment, which bans government funding of abortion. Still, McGaugh said, he believes he would be better off advocating for his views on the issue under a President Biden than trying to “have to advocate for basic things (under Trump) like truth and decency and, you know, doing things that your mother always asked you to do growing up.”

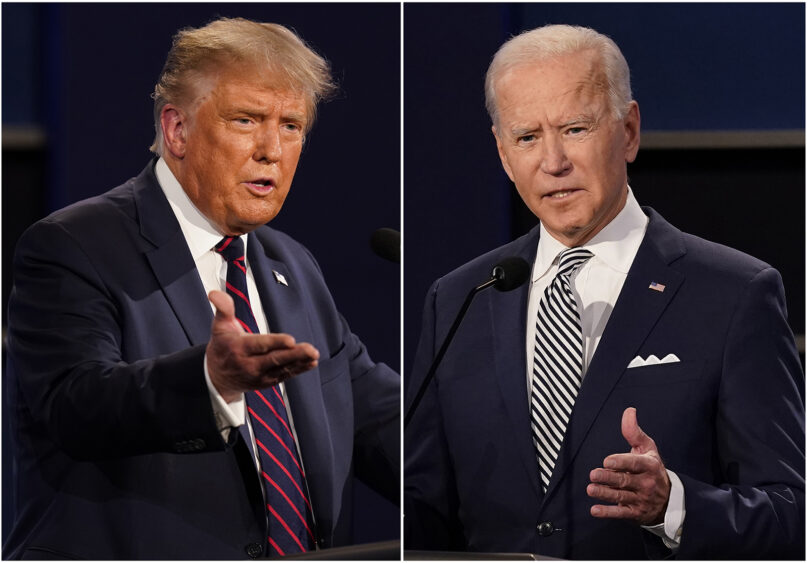

This combination of Sept. 29, 2020, photos shows President Donald Trump, left, and former Vice President Joe Biden during the first presidential debate at Case Western University and Cleveland Clinic, in Cleveland. (AP Photo/Patrick Semansky)

Faith and politics

McGaugh said his faith doesn’t tie him to a political party, but “it informs the values and the reasonings I would process through.”

Comparing his politics to the Old Testament nation of Israel while in exile, he said it’s important for him to “seek the welfare of the nation or the city in which you reside,” paraphrasing Jeremiah 29:7. This understanding influences his policy views, such as support for a more compassionate immigration system, better health care, how climate change affects the poor, and racism, which he called “America’s original sin.”

McGaugh, a dual major in political science and African American studies, believes that under the current administration, racism has been “inflamed by the rhetoric and policies from people in power.”

Guan’s parents are active in their church, a nondenominational Asian American church, and Guan became a Christian in his early teens.

“My faith is kind of the crux of why I voted the way that I did,” Guan said, and living out his faith means he wants his political views to “be an instrument for justice and for restoration.”

Guan’s parents aren’t the stereotypical Trump supporters. Like many immigrants, they struggled at first, having only $35 in their bank account at one point, Guan said, but were able to find a measure of success.

In China, Guan’s parents had participated in a protest against authoritarianism in Nanjing on the same day as the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre. Yet, they support Trump’s immigration policies and believe Black Lives Matter protesters were “just causing noise” and not protesting something legitimate. Guan said they also find Trump’s “law and order” pitches appealing.

“They did that thing (protest) against the government (of China), but they view it fundamentally differently from what’s happening now with our generation, with the issues of our time,” he said.

Reflecting on how to negotiate these differences with his family, Guan said, “I don’t have all the answers. Don’t even know how to deal with these conversations just yet.”

Healing broken relationships

Ryan has teamed up with New Moral Majority to create “Operation Family Meeting,” a pledge and discussion guide for Christian Biden supporters.

“Calling on all PKs, MKs, Ex-Youth Pastors & Worship Leaders, and all of you who still have an A.W.A.N.A. vest or who’ve spent their summers on a mission trip to Mexico!” the “Operation Family Meeting” homepage begins.

The problem, according to the pledge, is “(o)ur parents, our siblings, and our old church communities that are supporting Trump and the propaganda of white supremacy under the guise of protecting Christian virtues.” The discussion guide aims to help Biden supporters broach the topic of Trump support in a loving manner.

The need felt “very urgent,” Ryan said, because, “if we didn’t do something and share something now, we would have a generation of pastors’ kids and old church kids that just didn’t have a relationship with their parents anymore. They would have lost us.”

“Begin with love,” Ryan’s discussion guide advises. “If you go into this conversation in battle mode or with an air of superiority, you’ve already lost. It is natural for anyone to jump into a posture of defense if they feel threatened or attacked. You cannot insult or shame someone into agreeing with you.”

And, when it comes to the all-important issue of abortion, Ryan’s discussion guide (which comes from a point of view that supports abortion rights), advises, “Never begin a conversation with this topic when engaging with lifelong conservatives, evangelical Christians, or Catholics.”

Ryan Eller, 38, executive director of New Moral Majority, sees the group’s goals of healing broken relationships and electing Biden as mutually reinforcing.

“Regardless of what happens in the election, we need to heal,” he said. “We think the election of Joe Biden will help us heal a little more quickly, but we still need to heal regardless. … No matter what happens Nov. 3, we still have to be a family together or at least try to be a family again, and fight against this division we’ve had.”