Produced in collaboration with the Association of Religion Data Archives.

(RNS) — American churches have long been concerned about retaining the young people who have grown up in their pews. Christian denominations’ websites and publications are filled with analyses of why young adults leave church, and what pastors, priests and youth group leaders can do to bring them back into the fold.

A mountain of research suggests that churches are looking in the wrong place: If they want to understand why young adults do or don’t attend church, they should turn their attention away from church and focus on the childhood home. The strongest influence on any adult’s religious practice is that person’s parents.

Among the factors that can affect how strongly religious habits are passed down is how close parents are to their children: The better the relationship, the more likely the kids are to carry on. Traditions with a strong sense of identity, such as Latter-day Saints or Black Protestants, too, show higher rates of “transmission.”

A recent study I published in the academic journal Sociology of Religion shows another predictor: religious conservatism. Using data from the National Study of Youth and Religion, I find that when parents identify as religious conservatives, their young adult children (ages 23-28) attend church more often and report higher levels of faith.

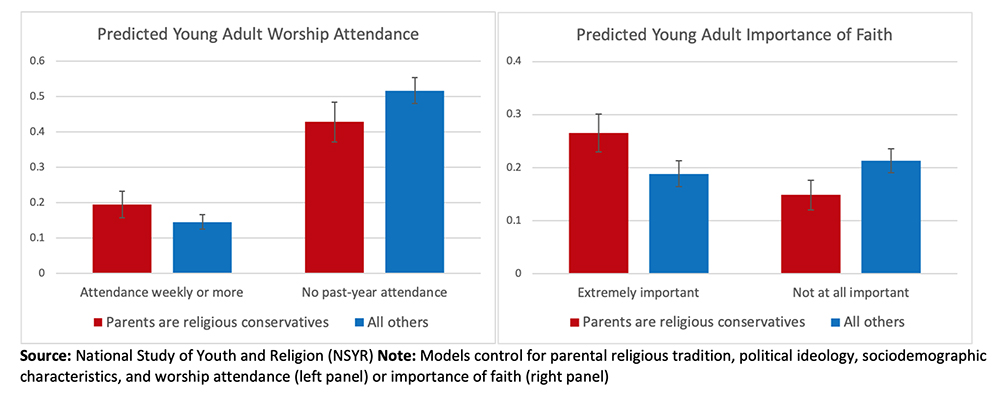

Children of religious conservatives have a predicted 19% chance of going to church at least weekly, compared with 15% of their peers from more moderate or liberal families. If we look at the probability of never attending after leaving their family’s home, this flips. A predicted 43% of children of religious conservatives have left the pews entirely, compared with 52% for the rest.

We see basically the same trends when we ask about how central their faith is in their lives. About a quarter of the children of religious conservatives can be expected to say faith is “extremely important,” compared with less than a fifth of less conservative churchgoers. Conversely, only 15% of the religious conservative group is predicted to say faith is “not at all important,” compared with 21% of all others.

This may seem like a no-brainer. Of course traditionally conservative faith traditions such as Southern Baptists will produce more religious kids than, say, Episcopalians. But importantly, these numbers adjust for key factors such as parents’ religious tradition, and political ideology.

This means that it isn’t just that evangelicals retain their youth more than mainline Protestants (though this is also true). If you take parents from any single religious tradition, with the same levels of faith and frequency of attendance, those who identify as religious conservatives will still produce more religious young adults in the next generation.

It’s reasonable to ask at this point: What is a religious conservative, exactly? It’s the sort of thing we may feel we intuitively understand, yet have trouble putting into words. The data can’t tell us exactly what people mean when they call themselves religious conservatives, and it’s probably not any one thing so much as a variety of characteristics with so-called family resemblances: biblical literalism, moral absolutism, belief in a personally engaged God, a desire for a strong role of religion in public life, or sexual traditionalism, to name a few.

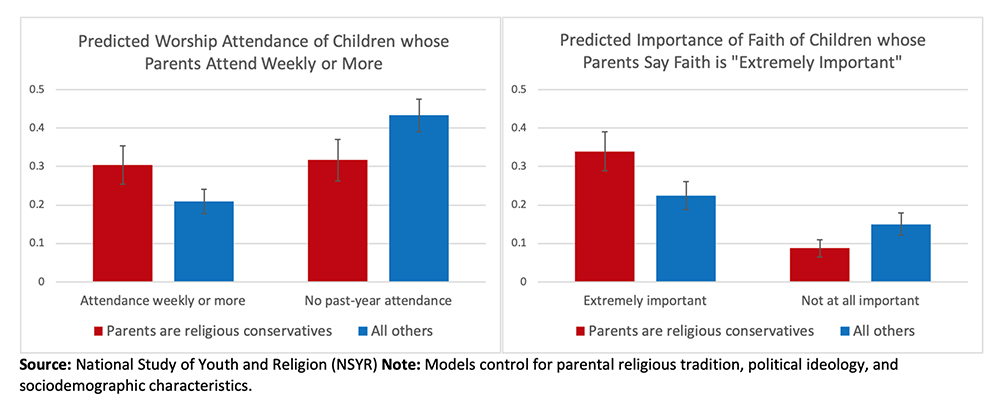

But we can answer a little what religious conservative parents do differently that promotes stronger transmission. One surprisingly straightforward explanation stood out above all the others: It’s the frequency of religious discussion at home while children are growing up.

But we can answer a little what religious conservative parents do differently that promotes stronger transmission. One surprisingly straightforward explanation stood out above all the others: It’s the frequency of religious discussion at home while children are growing up.

Specifically, in the first wave of the data collection, when children were 12-17 years old, they were asked how often their families discuss “God, the Scriptures, prayer, or other religious or spiritual things together.” This one measure explained roughly half of the difference in church attendance and faith between children of religious conservatives and their peers.

For churches concerned about how to keep younger people in the pews, the answer suggested here is: Start early, and work through parents.

For parents concerned about how to pass religion on to their kids, the answer is: Make it a part of daily life.

Research suggests that religiously liberal-leaning parents view openness and autonomy as important religious values in a way that conservatives don’t, and so worry more about forcing religion onto their children. Because of this, they use a lighter touch when it comes to religious socialization.

Their concerns may be reasonable. If the goal is to pass on the faith, however, this approach comes at a cost. When kids don’t experience religion as a regular part of family life in childhood, they’ll be more likely to leave and less likely to return in adulthood.

It’s worth noting that children’s religious belief and practice is being measured here during their 20s, which tends to be a low point in the religious life course. Many of them may return later in life, so we can expect the gap between this set of parents and children to narrow — but not to close entirely.

One more note: As we’ve been seeing overall cross-generational decline in religiousness for a long time now, with no sign of this trend stopping or slowing down, we can predict that even as each generation becomes less religious, those who are still religious are likely to be increasingly conservative.

Religiosity as a driver of American cultural conflict doesn’t look to be fading anytime soon.

(Jesse Smith is a Ph.D. candidate in sociology at The Pennsylvania State University. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)

Ahead of the Trend is a collaborative effort between Religion News Service and the Association of Religion Data Archives made possible through the support of the John Templeton Foundation. See other Ahead of the Trend articles here.