(RNS) — I did not watch the Super Bowl.

But I know enough about American popular culture to recognize the Super Bowl is a religious festival of the American year — complete with a sacred gathering (your closest friends, except not this year, I hope) and a sacred meal (chicken wings, beer, etc.).

This year, that American ritual moment also contained what every ritual moment contains — a sacred text.

I am talking about the Jeep commercial, with its narrator, Bruce Springsteen.

Let me, therefore, offer you a commentary on that text — what we Jews would call a Rashi, named after Judaism’s most significant commentator.

00:00-0:06: Springsteen as cowboy. Note the scuffed boots. If this surprises you, it shouldn’t. The Boss is a quintessential musical interpreter of what some would call “the real America,” whatever that means.

0:08: Smoke stacks. Industrial visual. Iconic of a failed economic base.

0:09: The chapel in Kansas, that stands at the exact geographical center of the lower 48 states.

Don’t be shocked. America is, in the words of Chesterton, “a nation with the soul of a church.” He is pointing to the great fact of the American civil religion — a civil religion of which Dwight Eisenhower could state “America is a religious nation, and I don’t care what religion it is.”

The light side of that civil religion is its openness. The chapel “never closes. All are more than welcome.”

But the darker side of that civil religion is its default setting is Christianity. The even darker side of that civil religion?

0:22: The major decoration in the chapel is a cross superimposed on the American flag. If the creators of this commercial wanted to give a shoutout to Christian nationalism, they succeeded. If not, they blew it.

A Jeep commercial that aired during the Super Bowl highlighted a chapel in Lebanon, Kansas. Video screengrab

0:23-0:55: Here comes the essence of his message. We need to reclaim the center, ideologically and politically. Fear is our enemy. Freedom is everyone’s inheritance — no matter who you are or where you are.

Now, do you doubt who the intended audience is? Those who live in the flyover states — which is where Bruce is driving around, in the middle of winter with the roof down — who often feel unseen, unheard, laughed at, ignored.

Many of those people undoubtedly showed up in Washington, D.C., on Jan. 6. But, Bruce is saying: “I hear you. I see you. You are part of this, but so is the immigrant, the member of a racial or sexual minority. This country belongs to everyone. Yes, you. But, far more than you…”

1:16: “We can make it to the mountaintop, and through the desert.” Nice move, Bruce. Because America belongs to those who share the vision of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. (“I have been to the mountaintop … “). Bruce is talking about Mount Sinai and the Israelites’ trek through the Sinai desert. Fellow Jews, that’s our Torah in there!

(Except: The myth of the “Judeo-Christian” tradition has allowed Jews to enter the country club of the American story. But, as for other religious traditions, not so much. If at all.)

1:24: Wait. Is Bruce lighting a yahrzeit candle?

1:30: Another shot of the church. Hmmm.

1:39: Yet another shot of the church. More “hmmm.”

In which case, you would be justified in believing the vision of a “reunited States of America” is a decidedly Christian one.

Several years ago, I attended a Catholic-Jewish conference at Notre Dame University. In an off-the-cuff remark, one of the Catholic priests in attendance said: “If you really want to know who the most important Catholic theologian in America is, it’s Bruce Springsteen.”

Springsteen is as Catholic as the late Leonard Cohen was Jewish. Check out “The Grace of God and The Grace of Man: The Theologies of Bruce Springsteen,” one of the finest books about religion and rock music. In an interview with Rolling Stone, Springsteen described his Catholic childhood as “an epic canvas and it gave you a sense of revelation, retribution, perdition, bliss, ecstasy.”

Like his blue-collar New Jersey background, his Catholicism infuses Springsteen’s writing.

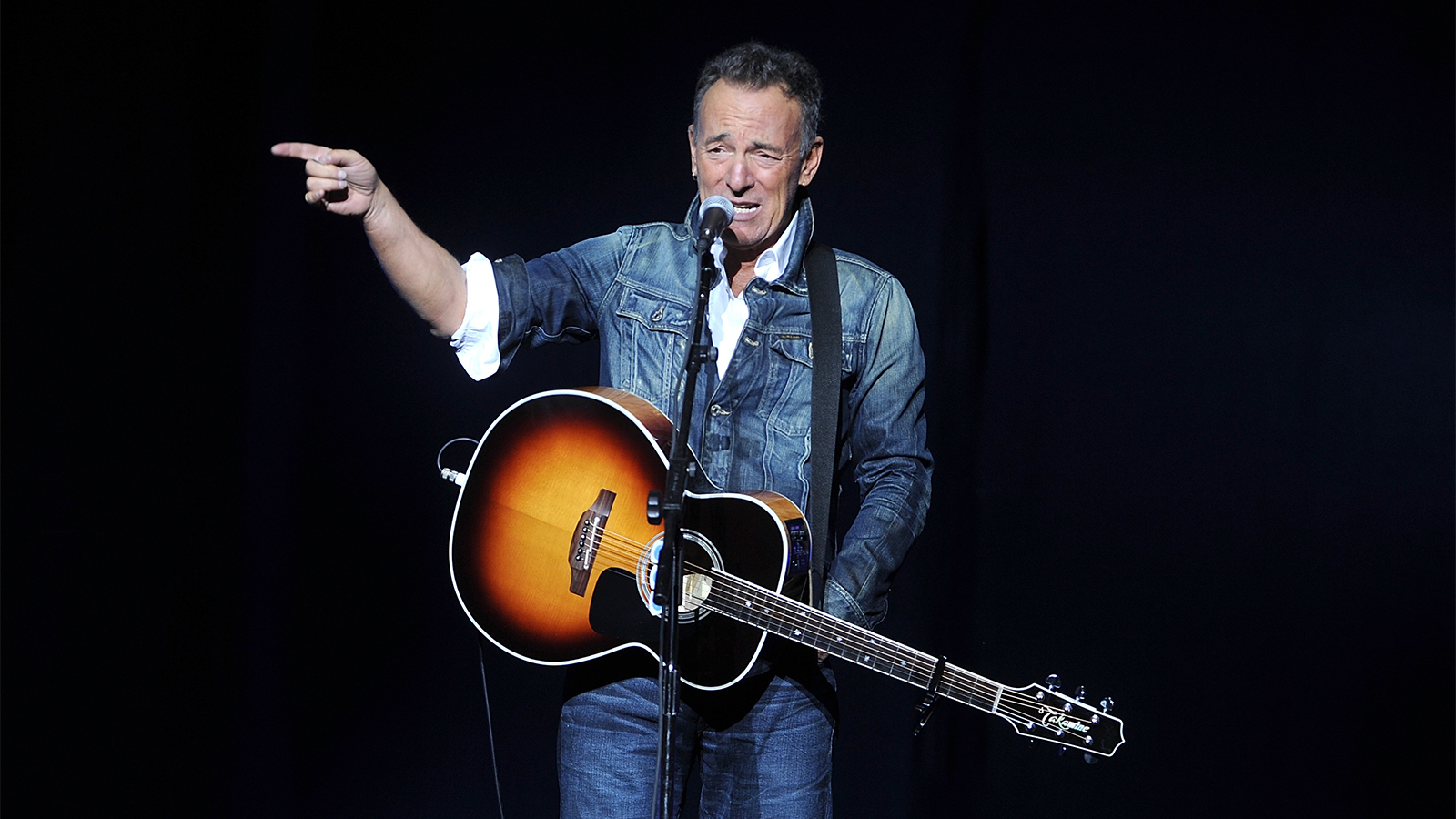

Bruce Springsteen performs at the 12th annual Stand Up For Heroes benefit concert at the Hulu Theater at Madison Square Garden on Nov. 5, 2018, in New York. (Photo by Brad Barket/Invision/AP)

For me, “Born To Run” was it — and it still is. When it came out, in 1975, critic Jon Landau proclaimed: “I have seen rock and roll’s future, and its name is Bruce Springsteen.” Bruce appeared, simultaneously, on the covers of Time and Newsweek.

It was, frankly, rock messianic. It was pure revelation — and redemption.

Nothing plays like the first side of that album. No first side of an album is as religious as that one.

From “Thunder Road“:

You can hide ‘neath your covers

And study your pain

Make crosses from your lovers

Throw roses in the rain

Waste your summers praying in vain

For a savior to rise from these streets

What is redemption, for Springsteen? Not the cross, but the car. “All the redemption I can offer girl is beneath this dirty hood.”

The mundane world is the place of redemption — where you work hard and wait to escape into the “night.”

We are “born to run.” And take it to the B side of the album, to the vastly underrated “Meeting Cross The River,” where something is waiting for the couple on the other side of the river.

Bruce’s characters are the (mostly Catholic) children of the suburban working class, hard-working people, who know there is something better waiting for them. It is a collection of secular redemptive elements — the night, the car, the highway, the girl. It’s not even Jesus. It’s Shabbat. It’s Jerusalem. It’s homecoming — to wherever that is.

That is a religious vision, filled with sin, atonement, redemption.

Is Springsteen’s vision of America a Christian nationalist vision?

I would be surprised. Springsteen is one of the most liberal-identified performers in American popular culture.

Does he believe in the American civil religion, which is not so vaguely Christian? Perhaps.

But, more than this: If Bruce does believe in sin, atonement and redemption, then it would not be illiberal to suggest the American story, broken and shattered as it is, is one of sin — against its minorities, especially African Americans. It is a story in which the original sin is one of hatred and division that lasts to this day. It is a story that needs atonement and offers the possibility of redemption.

Let there be no doubt. Whatever his religious vision, Springsteen is an American patriot. He knows we can get to the imagined promised land.

But only if we “center” ourselves — and include everyone in that great American conversation.

It will not be easy. It will be, frankly, uncomfortable.

But the alternative is not heaven.

It is hell.