A view of the Tsitsernakaberd Armenian Genocide Memorial Complex, a memorial to the victims of mass killings by Ottoman Turks during World War I, in the Armenian capital Yerevan, Armenia, Oct. 30, 2019. (AP Photo/Hakob Berberyan)

(RNS) — Several years ago, when travel was more common, I was on a plane, and I found myself talking to the passenger in the seat next to me. We exchanged professional credentials — I, a rabbi, he, a documentary filmmaker. We exchanged names, and when I noticed his surname, like mine, ended with an N, I asked him its derivation.

He confirmed for me what I had already guessed — that he was of Armenian extraction.

There was an awkward silence.

“You know,” I said, “I’ve always felt a great kinship with the Armenians. I …”

“I know,” he said, holding up his hand. “I know.”

I thought of that man today, as President Biden did what none of his predecessors would do.

He (finally) called the mass killing of the Armenians a genocide.

Why do I, as a rabbi, write about the Armenians?

Because the Armenians are our mirror.

Years ago, in a journal the name of which I cannot remember, I read these words by the poet Joel Rosenberg:

I count the ways we are alike

I cite the kingdoms of our former glory — which, for both of us, perhaps, had been a bit too much to handle,

As it has been ever since.

I cite our landless outposts

Of diaspora, strewn close along the rivers

And the shores of human habitation

That branch outward from the founts

Of Paradise. I cite our neighboring

Quarters in the walled Jerusalem,

Our holy men in black, our past

In Scripture, and our overlapping

Sacred sites. I cite our reverence for family ties, the polar worlds of grandfathers and grandmothers …

Our Middle Eastern food, our enterprise, our reedy and Levantine tunes.

Our immigration histories, the grainy profiles

Our ironic manner, our eccentric uncles. Our clustering in cities

Our cherishing of books

Our vexed and aching homelands.

Oh, yes: our adjacent quarters in Jerusalem, where the walls bear the maps of the massacres. Where the walls bear howls of remembrance.

Let us retell the story.

The Armenians were a distinctive national and religious group within the Ottoman Empire — a Christian minority within a Muslim domain. As the 20th century dawned, the Turks came to view the Armenians as a foreign element — in much the same way as Europeans perceived Jews to be a foreign element. Like the Jews of Europe, the Armenian Christians challenged the traditional hierarchy of Ottoman society. Like the Jews of Europe, they became educated, wealthy and more urban. Like “the Jewish problem,” there was pervasive talk in Turkey of “the Armenian question.”

During World War I, the Turks embarked on a massive plan to exterminate the Armenian nation. By February 1915, Armenians serving in the Ottoman army were turned into labor battalions. They were either worked to death or killed.

By April, the remaining civilians were deported from eastern Anatolia and Cilicia toward the deserts near Aleppo. It was an early form of ethnic cleansing. Again and again, Turkish and Kurdish villagers attacked the lines of Armenian deportees. Armenians died through deportation, mass murder and starvation.

Children and young females were often spared — through forced conversions to Islam, adoptions and slave labor. Torture was particularly cruel; in his memoirs, the U.S. Ambassador Henry Morgenthau Sr. wrote that the Turks had worked, day and night, to perfect new methods of inflicting agony. Morgenthau wrote the Turks even delved into the records of the Spanish Inquisition and adopted its methods. There were so many Armenian bodies dumped into the Euphrates the mighty river changed its course for a hundred yards.

Between 1915 and 1923, approximately one-half to three-quarters of the Armenian population was destroyed in the Ottoman Empire.

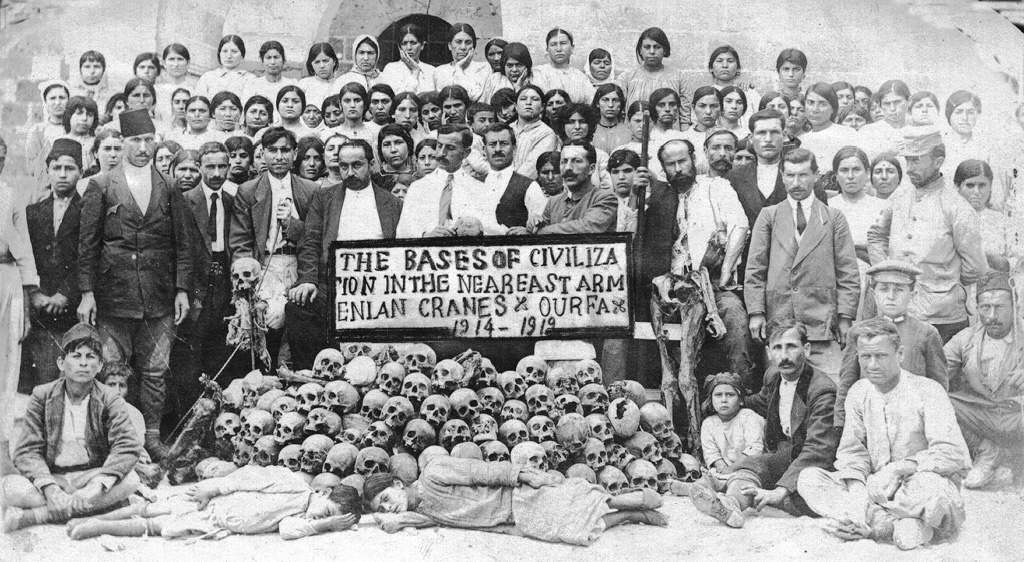

Skulls of Armenians massacred in Urfa, surrounded by Armenian dignitaries and women from the women’s shelter in Urfa’s Monastery of St. Sarkis, in June 1919. Photo courtesy ABGU/Creative Commons

And in the United States? Parents cajoled their children to be frugal with their food “for there are starving children in Armenia.” In 1915 alone, the New York Times published 145 articles about the Armenian Genocide. Americans raised some $100 million in aid for the Armenians. Activists, politicians, religious leaders, diplomats, intellectuals and ordinary citizens called for intervention — an intervention that did not come.

The Armenian massacre was the model of all modern genocides. Not only the act of genocide itself, but also the passive amnesia about that genocide. “Who talks about the Armenians anymore?” laughed Hitler.

Years ago, when this subject first grabbed my soul, I started thinking about the comparisons between the Jews and the Armenians — not only our cultures, not only our suffering — but our responses to that suffering.

A story: One day in 1915, the Turks started deporting the 800 families of Kourd Belen, near Izmir. The pastor of the village was an 85-year-old priest, Khoren Hampartsoomian. As he led his people from their village, neighboring Turks came out to view the exiles. They taunted the priest: “Good luck, old man. Whom are you going to bury today?”

The old priest replied: “God. God is dead and we are rushing to his funeral.”

An echo. In “Night,” the late Elie Wiesel writes about a child hanging from a gallows, twisting slowly in the wind, his small body too light to die immediately. The agony lingered long and painfully.

“Where is God?” cries a prisoner.

“Where is God? Hanging on the gallows.”

After the Shoah, Jewish theologians cried out to the God who they believed had betrayed them. “O God, how could You do this to us, the children of Your covenant?”

So, too, Armenians. Doris and Arda Melkonian are sisters who study in Fuller’s School of Theology.

People attend a service at a genocide memorial on Armenian Genocide Remembrance Day, April 24, 2017, in Vedi, Armenia. Photo by Armineaghayan/Creative Commons

Consider their lament:

Armenians are proud to have been the first nation to accept Christianity as a state religion in AD 301. Therefore, it is difficult for Armenians to comprehend why such horrors would befall us who have chosen Christ. We who have been faithful to God for over 1,600 years, resisting pressures over the centuries to convert to other faiths, from Zoroastrianism in the 5th century to Islam in more recent times. We who have fought countless wars to maintain our faith in God, demonstrating our loyalty to him, have felt a profound sense of abandonment. So we raise our voices to God and cry out, “Why?”

Our teachers cried out of the depths of their understanding of the covenant: “We must have sinned. God has used the Nazis as a club against us.”

So, too, Armenian theologians. In the words of Shushan Khachatryan:

One of the widely-spread points is that the Genocide was God’s punishment because the Armenians lived as atheists and were a Christian nation at the same time. They were obliged to disseminate the light of Christianity among their neighbors, for example, among the Turks, but they failed to do so.

Jews will note, with solemnity, that Yom Ha Shoah and the day of remembrance for the Armenian genocide are almost two weeks apart. Others will remember that it was a Polish-Jewish activist, Raphael Lemkin, who worked himself to death to get the nations of the world to adopt laws against genocide.

Let us note that. Let us remember.