(RNS) —Longtime faculty parliamentarian that I am, I write today in praise of Henry Martyn Robert, unsung hero of American civilization.

While you are not likely to have heard of him, you have almost certainly been subjected to the work of which he is the eponymous progenitor: “Robert’s Rules of Order.” For well over a century it has been the bible of deliberative bodies from sea to shining sea.

Robert the man was a scion of Huguenot South Carolina, born in, yes, Robertville, in 1837. His father was a Baptist preacher and educator who moved the family to Ohio and sold his slaves before the Civil War. In 1857, Henry graduated from the U.S. Military Academy at West Point with exceptional grades and went on to a distinguished career as a military engineer, ultimately becoming the general in charge of the Army Corps of Engineers.

RELATED: As United Church of Christ takes on race and LGBTQ issues, consensus reigns

The story goes that during the Civil War he was tapped to run a town meeting in New Bedford, Massachusetts, where he’d been sent to manage construction of naval defenses against possible Confederate attack. Embarrassed that he had no idea how to run such a meeting, he undertook the study of parliamentary procedure that became his enduring passion.

Assigned to San Francisco as chief engineer of the military division of the Pacific from 1867 to 1871, Robert walked the progressive Christian walk, supporting women’s rights, working to improve the plight of Chinese immigrants and establishing a Society for the Rescue of Fallen Women.

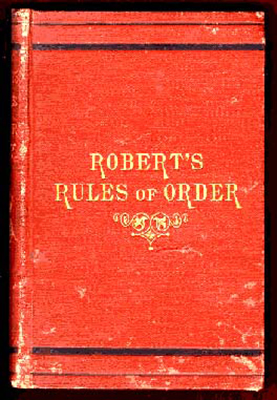

1876 cover of “Robert’s Rules of Order.” Photo courtesy of Creative Commons

He also threw himself into Baptist governance, a famously fractious world thanks in no small measure to a theology that privileged the individual conscience over ecclesiastical creeds and polities.

“One can scarcely have had much experience in deliberative meetings of Christians,” he once told his co-religionists, “without realizing that the best of men having wills of their own, are liable to attempt to carry out their own views without paying sufficient respect to the rights of their opponents.”

It was precisely in order to ensure respect for the rights of opponents that Robert wrote his “Rules,” the first edition of which appeared in 1876. By the end of the century it had driven any competitors from the field. Half a million copies sold before the revised edition appeared in 1915.

In recent years, “Robert’s Rules” has received a certain amount of criticism for privileging contention over consensus, but this fails to grasp the author’s deep insight that consensus is easier to achieve when the parties know that, in the end, the matter will come to a vote.

RELATED: Campus friendships can end a civil war before it start

Accounts of Robert’s own service on many boards and in many organizations make clear that he himself worked hard to bring consensus about, and usually succeeded. What his rules aim to do is keep the entity intact and functioning healthily when consensus fails — such as happened in his day when his native South Carolina led the Southern states to secede from the Union.

As he summed up his philosophy in Parliamentary Law, a treatise published just before his death in 1923:

The great lesson for democracies to learn is for the majority to give to the minority a full, free opportunity to present their side of the case, and then for the minority, having failed to win a majority to their views, gracefully to submit and to recognize the action as that of the entire organization, and cheerfully to assist in carrying it out, until they can secure its repeal.

Sad to say, this is a lesson that the minority in Robert’s democracy has, in our day, managed to unlearn.