(RNS) — Days into writing her new book, Lisa Sharon Harper stumbled across a Zillow listing for a house in South Philadelphia that had been her grandmother’s home. Though at the time she had no intention of leaving Washington, D.C., the author and Christian activist surprised herself by moving close to the place her family resided for 70 years.

But the neighborhood barely resembles the thriving Black community her grandmother knew. Ravaged by drug wars, then chewed up and spit out by urban renewal projects, the area today has been gentrified — “dogs and lattes and white folks everywhere,” as Harper put it.

But as she writes in “Fortune: How Race Broke My Family and the World and How to Repair It All,” she felt her ancestors calling her back to reclaim the place. “Perhaps the layered trauma of this land is the same layered trauma that has lived in my body,” she writes.

The book traces her family history to tell the story of America, pulling together three decades of Harper’s research into her family to examine how the decisions (and religion) of those in power deprived Black Americans of homes, prosperity, history and humanity. Yet the book, set to be released by Brazos Press on Tuesday (Feb. 8), is also written with an eye toward redemption.

Harper spoke with Religion News Service about how race corrupted America and Christianity, and her belief that truth-telling, repentance and forgiveness can repair what is broken. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Fortune, your ancestor, is just one of many family members you write about. Why did you choose her name for the title of your new book?

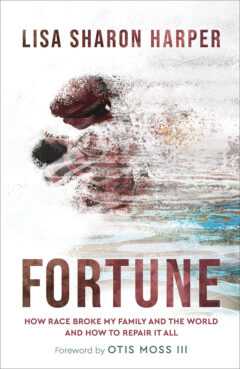

“Fortune: How Race Broke My Family and the World and How to Repair It All” by Lisa Sharon Harper. Courtesy image

Fortune is likely my seventh-times great-grandmother. She was born in Maryland in 1687, only 23 years after the colony’s very first race law. Her life, her body, her spirit, it all absorbed the wrath of those first laws, those laws that shaped the possibilities and the fortunes of her descendants forever. Her mother was a white woman who had a child by a Senegalese man named Sambo Game, and after living the first 18 years of her life free, she was hauled into court and sentenced to indenture until the age of 31.

As I was researching her and her descendants, and realizing that we were connected, it struck me that this is much more than family research. I’m actually discovering how America was made. I’m discovering the racial roots of America. And one of the things that I realized in my research is that none of these laws just — “poof” — came into being. They came from choices that the legislators made in that era that were always to benefit them and their economic standing.

You write: “Any attempt to repair what race broke in our nation must contend with what race broke in our faith.” Why can’t we effectively pursue racial justice without reckoning with the corruption of Christian faith?

Seventy-percent of Americans claim to be Christians. If you don’t address their broken faith, then you cannot convince them of their need for repair. A central way that race broke the world was through the partnership of the church. Churches became the theological justifiers for slavery. It has been the rare but mighty cases that have revolted from that inertia and mounted a countermovement.

Jesus himself was a brown colonized man, who came from a brown colonized people who were serially enslaved. The faith was corrupted by the construct of race and racial hierarchy. So there’s no way for us to repair what race broke in the world without addressing both the laws and the religious worldviews that underpin those laws.

You argue that reparations are key to repentance. Can you say more about the connection between repentance and reparations?

Reparation literally comes from the root “repair.” Reparations exist to repair not only the peoples who were broken by oppression, but the relationship between the oppressing people in government and those they oppressed. There are layers upon layers of injustice that have never fully been repented of. Repentance is turning and walking in another direction. It’s not saying “I’m sorry” — that’s confession. Repentance is to “do” sorry, to do things differently. That’s why reparations is repentance. It’s our nation choosing to do differently, to order ourselves differently.

RELATED: Red Lip Theology: Candice Benbow’s love letter to Black women in the Black church

You write that forgiveness is an essential component of repair, yet some argue that granting forgiveness actually empowers the oppressor.

Forgiveness is a must, because without it there’s no way forward. There are things that can never be restored or repaired. A million and a half people rest at the bottom of the ocean, thrown overboard in the midst of the Middle Passage. Millions of African Americans live under the soil of the South, from the Southern slave-ocracy, who died without their names recorded anywhere. We have family members who were lost to medical racism, whose futures were stunted by poor education. That’s not going away. My grandmother was beaten to death by a crack addict after drugs were pumped into this community in the drug wars. I will never get her back. We have experienced, as a people, trauma upon trauma upon trauma.

If we hold onto the demand for those things to be repaired which cannot be repaired, if we hold onto that pain and demand restoration when it’s impossible to restore the lives lost and communities destroyed, then we are the ones who rot from the inside. We are the ones whose bodies break down from the stress.

Forgiveness releases us. It cuts the tie between us and our oppressor. Forgiveness is for our sake, not for white folks’ sake. To be clear, the chapter on reparations comes first. And I’m not saying forgive it all; I’m saying forgive that which cannot be repaired, and which can never be restored. And that which can be repaired and restored, must be repaired and restored. That’s how we will repair our relationship.

Many of your family stories include painful elements of violence and abuse. How do these heart-wrenching parts of the book fit into the need for repair?

In order for us to repair what race broke in the world, the first thing that we need to do is to tell the truth. The truth has been suppressed. We have the myths of white nobility, white goodness, white rightness, because the details have been hidden. So when we ask the question of who we are and how we got here — how did we get to Jan. 6, how did we get to 34 voter suppression laws being passed in 19 states last year? — we got here through 400 years of choices to craft a society that bows to the god of racial hierarchy.

My family was enslaved because of the choices people made. When David Ballard came south to continue his practice of slavery, that choice impacted the life of Lea Ballard, the last enslaved woman in our family. She lost five children as a result of that.

The policy decisions that were made are not just lines in a history book. They broke up families. My great-grandfather owned a block of homes in the community of Elmwood, Philadelphia, and it was taken by eminent domain. It’s now Interstate 95.

Right now we have a window of opportunity where we can choose a new way to be together in the world. We can choose the way of love, the way of mutual respect, the way of repair. We can choose the way of truth-telling in order to reckon with what happened, so that it never happens again.

RELATED: Christian writer Danté Stewart seeks revelation in Black experience