(RNS) — Let’s start with three underreported facts about women in Utah.

First: On Valentine’s Day in 1870, a 23-year-old schoolteacher in Salt Lake City became the first American woman to cast a vote in a public election.*

Second: When Utah was upgraded from a territory to a state in 1896, it enshrined women’s political equality in its state constitution. Only two other states had yet done so.

And third: Immediately after entering the Union, Utah became the first state to elect a woman to serve in its state legislature. Martha Hughes Cannon, a doctor, beat out her own husband for the seat and used her time in office to help create the Utah Department of Health.

So what the heck happened? Today, Utah is known for being at the opposite end of the spectrum of women’s equality and rights. Nationally, for example, the gender pay gap is about 18%, meaning women earn 82 cents for every dollar that men do for full-time work. In Utah, it’s 30%, making Utah one of the worst states for women financially.

“Pioneering the Vote: The Untold Story of Suffragists in Utah and the West” Courtesy image

That’s not the only problem. For the last four years, Utah has earned the dubious distinction of ranking 50th of all 50 states in terms of women’s equality, determined by 17 different metrics including educational achievement, earning power, representation in government, ownership of business and other factors.

One key to implementing equal rights may be looking backward to a time when things looked more hopeful for Utah’s women, especially politically. Neylan McBaine’s 2020 book “Pioneering the Vote: The Untold Story of Suffragists in Utah and the West” aims to do just that.

“How does nobody know this?” McBaine asked when she began work on the project in 2016, referring to Utah women’s successful fight for suffrage half a century before the right was granted to women nationwide. While scholars and historians have long known about the role Utah women played in the suffrage movement, most ordinary citizens did not.

The non-profit organization Better Days 2020, which McBaine co-founded, began approaching institutions and individuals for funding to raise the visibility of women in Utah’s history. They trained 1,000 teachers across the state, developed a website as a gold mine of information, created a Utah license plate to celebrate women’s suffrage and even raised funds for a statue of Martha Hughes Cannon to be on permanent display in the U.S. Capitol building.

Most people, McBaine notes, have been excited to learn how Utah’s women were “leading out” in the fight for women’s equality. But she noticed a difference in how different groups received their requests for support. Non-LDS institutions, she says, were more receptive than the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints was, despite the fact that the major players in the Utah suffrage movement were all Mormons.

Neylan McBaine poses for a portrait at her home Monday, Nov. 15, 2021, in Holladay, Utah. (AP Photo/Rick Bowmer)

Why the hesitation? McBaine believes it’s because of polygamy, which many of Utah’s most visible women practiced in the 19th century. Dr. Cannon, for example, was the fourth wife of six.

“When we went to church institutions or to people who were members and told them this story, their response was ‘We can’t talk about that. That’s going to be embarrassing for us,’” McBaine said. “It was really interesting the way the story was welcomed and greeted by nonmembers but less so by members. Today, we don’t know how to wrestle with the fact that this great triumph was intertwined with plural marriage.”

McBaine also senses that some more conservative voices within the church, of which she is also an active member, may not be fully on board with the notion of women’s advancement in public life and politics. After encouraging women to vote and run for public office in the 19th century, the church had a major retrenchment in the 20th, promoting the idea of the home as women’s sole sphere and vigorously organizing in the 1970s to defeat the ratification of the Equal Rights Amendment.

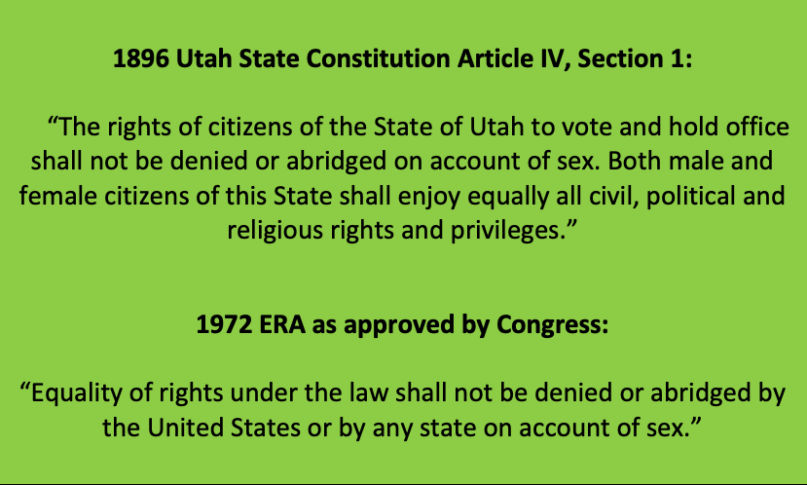

And that’s ironic, McBaine notes, because the language of the ERA as drafted in the 20th century was partly based on the longstanding example of the Utah State Constitution, which promised that “the rights of citizens of the State of Utah to vote and hold office shall not be denied or abridged on account of sex.” The 1972 ERA wording was that “Equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of sex.”

“We’ve been living under that law all this time, but because there’s no case law, people don’t really know it’s there,” McBaine said. “A lot of fears surround the ERA, but we could have seen they were unjustified by looking at our own state constitution.”

McBaine sees reasons for hope, both for women in Utah and women in the LDS Church. For one thing, this book was published by Shadow Mountain, the national imprint of Deseret Book, the church’s official publishing house. Which means the church has a desire to see this story recovered.

Also, McBaine sees greater openness in the church to the voices of women, including more attention to Heavenly Mother, “and normalizing Heavenly Parents. It’s been a lifeline for a lot of people.”

That doesn’t mean there isn’t room for improvement. McBaine recently attended a ward conference in which there were 37 men on the stand — including the whole stake high council and many priesthood leaders — and just one woman, who was directing the congregational hymns. “I think there is absolutely no excuse for that,” McBaine said.

She continued, “there needs to be a general reassessment of gendered leadership from the top down. I don’t know what more we can do on the local level to really change administration. It’s either got to be a massive, global grassroots shift or come from the top down.

“I will say that the next thing that needs to happen is that girls need to pass the sacrament. And soon, or else we’re just going to continue losing my own girls and the girls within their generation.”

*Utah was not, however, the first state or territory to grant women the right to vote: Wyoming earned that distinction in December of 1869. Wyoming just hadn’t held an election yet to put that new right into practice.

Related content: