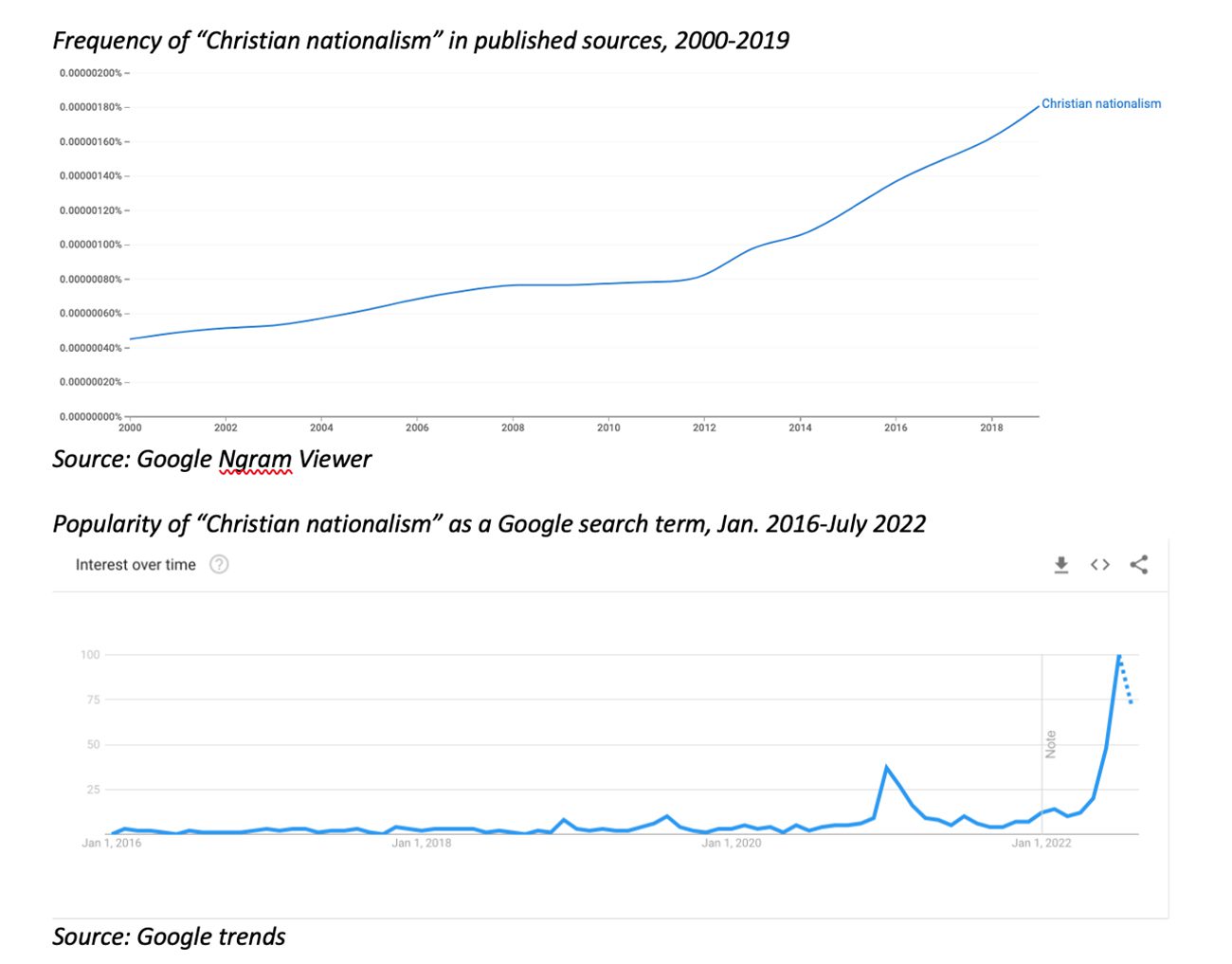

(RNS) — A few short years ago, “Christian nationalism” was rarely mentioned. Now, as the below analysis of Google trends shows, the culture is buzzing with it, from academic conferences to New York Times headlines, politicians’ tweets and pastors’ sermons.

As the first graph shows, the term’s usage in printed sources started picking up in 2011 and has kept climbing ever since. It generally takes a few years for catchphrases to make their way from the publisher to the dinner table, but the second graph, showing Google searches for “Christian nationalism,” shows that interest spiked suddenly after Jan. 6, 2021, and recently hit a new high point.

As the first graph shows, the term’s usage in printed sources started picking up in 2011 and has kept climbing ever since. It generally takes a few years for catchphrases to make their way from the publisher to the dinner table, but the second graph, showing Google searches for “Christian nationalism,” shows that interest spiked suddenly after Jan. 6, 2021, and recently hit a new high point.

So what is Christian nationalism exactly?

Typical definitions go something like: Christian nationalism is a belief that the United States was, is and should remain a Christian nation. Christian identity is an indispensable part of American identity, and this should be reflected in our political institutions. Though adherents of Christian nationalism may not typically say this part out loud, it follows that non-Christians — and perhaps other ethnocultural minorities — are somehow less American or should occupy a lesser status in American society.

The concept gets tricky when we apply it to particular cases. Is the motto “In God We Trust” on American currency an instance of Christian nationalism? What about President Joe Biden taking the inauguration oath on a Christian Bible? Are Christian pro-life organizations that advocate anti-abortion public policy engaging in Christian nationalism? When conservative Christians cheer for public funding for religious schools, football coaches’ postgame prayers or bakers’ and florists’ refusal to service same-sex weddings, are they taking up the Christian nationalist cause?

“The Religion of American Greatness: What’s Wrong With Christian Nationalism” by Paul D. Miller. Courtesy image

Christian scholar Paul D. Miller, a former White House aide and now a professor at Georgetown University’s School of Foreign Service, has thought a great deal about these questions. His recent book on Christian nationalism is the most thorough and balanced treatment of the topic thus far.

Miller shares the concern of other scholars that Christian nationalism is real, pervasive and dangerous, but he draws an important distinction that has been mostly absent from the conversation: between Christian nationalism, and Christian republicanism (small-r).

What is Christian republicanism exactly?

Christian republicanism is a belief that liberal democracy is the system of government most consistent with the principles of Christianity. If humans are sinful, fallen creatures, then limited government and separation of powers offer an effective means of protecting us from our own worst impulses. If every human being was created in the image of God, then each individual has an inviolable dignity that should be recognized in the form of codified political rights.

Liberal democracy is thus the most fundamentally just political arrangement for Christians and non-Christians alike. Christians can (and should) participate in politics, and pursue policies informed by their faith, but should do so strictly within the boundaries of liberal democracy.

Christian nationalism and republicanism agree on some things, but here is where they diverge: Christian nationalism argues that liberal democracy cannot exist without a Christian culture, and government should work to preserve that culture, even at the expense of equal rights for non-Christians. By contrast, Christian republicanism argues that liberal democracy can survive and thrive in the absence of a Christian culture, as it does in much of the world (and increasingly in the United States). When it comes to American political institutions, democracy comes before Christianity.

Can we tell these two approaches apart in practice? Sometimes, yes. When rioters waving Christian flags and Bibles storm the Capitol to overturn an election, when Donald Trump tells a Christian crowd that “(in) a Trump administration, our Christian heritage will be cherished, protected, defended, like you’ve never seen before,” or when evangelicals declare Trump the new King Cyrus come to deliver them from bondage, these are instances of Christian nationalism.

In this Jan. 6, 2021, file photo, a man holds a Bible as Trump supporters gather outside the Capitol in Washington. The Christian imagery and rhetoric on view during the Capitol insurrection are sparking renewed debate about the societal effects of melding Christian faith with an exclusionary breed of nationalism. (AP Photo/John Minchillo)

When Christians mount a campaign at both the institutional and grassroots levels to advocate policies and judicial appointments favorable to religious liberty and restrictions on abortion, they are operating within liberal democracy’s framework of representative government and the separation of powers. These are instances of Christian republicanism.

This distinction is helpful, but leaves gray areas that call for discernment. The true extent of Christian nationalism can be hard to pin down because the Christian right contains a mix of nationalism and republicanism. Many conservative Christian leaders proclaim a commitment to America’s founding documents, to liberty and justice for all, but some apply this commitment selectively, marching for religious liberty or the rights of the unborn, but remaining conspicuously silent when it comes to the country’s legacy of racial injustice.

Some observers charge that the Christian right is nationalist through and through and only uses the language of republicanism as a smokescreen. It seems more plausible and more charitable to suppose that nationalist and republican impulses coexist in tension with each other. Political coalitions (not to mention individuals) are complex, and capable of holding contradictory views.

Among opponents of Christian nationalism, then, the goal shouldn’t be to decisively defeat the Christian right, but to bring out the best, most republican version of it.

Given Miller’s distinction between Christian nationalism and republicanism, in addition, we should think carefully how we use the Christian nationalist label. It may be inaccurate and unfair, for one thing. But there’s another reason to be cautious: Calling people Christian nationalists might bring out the Christian nationalist in them.

The tribal nature of our current politics can seem less like a civil process for solving social problems than a “Squid Game” tug of war. We care less about what people believe than the tribe they belong to. We police the tribal boundaries with labels and epithets such as “woke” and “socialist,” which translate to “suggesting social justice exists and America needs fixing.”

There is a very real danger of “Christian nationalism” taking on the same function. If used too broadly, the term loses its descriptive value and simply becomes a new tribal signifier, translating to “Any engagement by conservative Christians in political life.”

Before lumping the entire religious right in with Christian nationalists, we should ask ourselves: What happens if they take this message seriously? When people hear the label applied to them, they aren’t wrong to fear that their political opponents want to drive them from the public square entirely. There’s nothing like the perception of an existential threat to unite disparate groups against a common foe while undermining commitment to the loftier ideals of democracy. Who has time for principles when survival is at stake?

Scholars of Christian nationalism are correct to note that it is fueled by a persecution narrative, but seem not to notice how throwing around the label helps make that narrative more plausible for more people.

There are more promising approaches to opposing Christian nationalism. Political science research suggests that we shouldn’t give up on dialogue. Avoiding political epithets and simply talking, listening and sharing in a spirit of goodwill can go a long way toward opening people up to other views.

(Jesse Smith is a Ph.D. candidate in sociology at The Pennsylvania State University. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)