(RNS) — This essay will begin with a sad story — about a family in turmoil. Their story mirrors what is happening in the larger society — the struggle over politics, culture and how to engage each other on those topics. Join me in a conversation with David Bernstein and Rabbi Amy Wallk as we discuss the ramifications of far-leftist politics, cancel culture and antisemitism.

Click below to listen.

I tell this story with the permission of the person involved.

It is not pretty.

A man came to see me in my office, very distraught. His two adult daughters have cut off all communication with him.

Why?

Because they disagree politically. The parents are conservative; the children are far left. They have accused their parents of being racist, misogynistic, etc.

I know this man and his wife. True, they are political conservatives. It is also true that they are on the board of a soup kitchen. They serve food in a church in one of the most impoverished areas of south Florida. We might disagree on policy issues, but these people are hardly racist.

The man tells me, through tears, that he is approaching 80 years old: “Who knows how much time I have left? We want our children! We want our grandchildren! Our love for them is far bigger than a political party!”

This poor man. This poor family. My heart breaks for them.

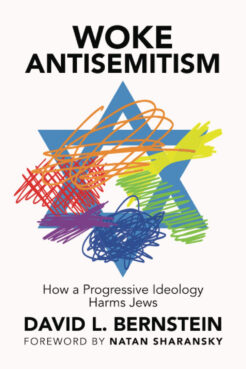

This story sat with me as I read David Bernstein’s new book “Woke Antisemitism: How a Progressive Ideology Harms Jews.” David is a veteran Jewish communal leader, a classic liberal (as am I) and the founder of the Jewish Institute for Liberal Values.

“Woke Antisemitism: How a Progressive Ideology Harms Jews” by David Bernstein. Courtesy image

Bernstein takes the reader on a tour of “woke” ideology. I would have preferred the label “radical left,” because the right, especially the governor of Florida, has hijacked the term “woke” to refer to anything they don’t like. They have made it a convenient label for their political opponents. (Since I am one of them, call me, in that sense, “woke” — proudly.)

I agree with much that is in this book. I quibble with other things. Its greatest gift is that it criticizes various trends in American political culture — in particular, the tendency to engage in binary thinking — “You’re either for us or against us.”

What did I appreciate, in particular?

First, there are the antisemitic manifestations of the radical left, especially on the college campus. Jews are seen as uniquely privileged, and even complicit in white supremacy. In March 2017, fliers calling for an end to “Jewish privilege” appeared on the campus of the University of Illinois in Chicago.

Bernstein quotes Pamela Paresky: “Jews, who have never been seen as white by those for whom being white is a moral good, are now seen as white by those for whom whiteness is an unmitigated evil.”

I have known about such antisemitism for more than 40 years, first encountering it when I was a student at college. It began with criticism of Israeli policy, but eventually it segued into a negation of Israel itself. Once upon a time, in medieval culture, the Jewish people was the incarnation of the devil. Now, Israel has assumed that role.

A post-doctoral student at Harvard said to David Bernstein: “I wanted very much to express my sympathy with Israel but knew that three professors I needed for career advancement would derail me.” He is not alone. This should send shock waves through our collective conscience.

What are the roots of this current wave of anti-Israelism and antisemitism?

It began in Durban, South Africa, 2001, at the World Conference against Racism. It was, by all accounts, a Woodstock of Israel-blaming, a renewal of the “Zionism is Racism” canard and blatant antisemitic imagery.

David says the radical left has become “Durbanized.” I agree.

Amazing and disturbing: People tend to deny, minimize or falsely contextualize the presence of antisemitism among their political friends.

Among those on the right: “Those people aren’t antisemites; they’re merely speaking out against the liberal elitists.”

Among those on the left: “Those people aren’t antisemites; they’re just anti-Israeli.”

As Professor Deborah Lipstadt — as impeccable an authority on antisemitism as you can find — has said: “If you only see the antisemitism on the part of your political enemies, then you are not seeing antisemitism. You are, rather, engaging in politics.”

Second, the nature of “cancel culture.” Which is precisely what happened to the parents in my opening story. Those parents got cancelled.

Cancel culture is not the same as getting fired because of your criminal behavior. It is not the same as getting fired because you have not fulfilled your professional obligations or because you have run astray of HR standards.

To quote Bret Stephens: “Cancel culture is a highly effective social-pressure mechanism through which the ideological fixations of the aggrieved and truculent few are imposed on the fearful or compliant many by means of the social annihilation of a handful of unfortunate individuals.”

Cancel culture exists, both on the left and on the right, as this article in the current issue of “Sapir Journal” makes clear.

I have felt it coming from both sides. In my career, people have harshly criticized me and cancelled me for being too pro-Israel. I have also been harshly criticized and cancelled for being insufficiently, in their minds, pro-Israel. Because I have disagreed with various Israeli policies and expect to add to that list, I have found myself with the label of “self-hating Jew,” or “JINO” (a Jew in name only) — and worse.

And yes, it can get very nasty and very personal. It can affect your professional future in the Jewish community.

But, let’s focus more clearly.

When those on the right speak out against cancel culture, it’s often because they want an open forum to express bigoted ideas — sometimes with a vulgar swipe at sensitivity itself.

I have no patience, nor time, for those people.

My problem with the cancel culture on the left is that it pretends there are only certain acceptable interpretations of social and political issues. Too often, failure to abide by those interpretations can lead to ostracism, loss of reputation, relationships and, yes, career opportunities.

Again, Bret Stephens: “It is why more than 60 percent of Americans admitted in 2020 that they have views they are afraid to share in public, and another 32 percent fear that their job prospects could be harmed by speaking their mind.”

This is anti-intellectual and anti-Jewish. In his essay in “Sapir,” Rabbi David Wolpe reminds us about the sacred Jewish idea of makhloket, controversy; of eilu v’eilu, of seeing different possibilities and nuances and realizing they are refractions of the holy.

That sense of diversity is baked into the pages of the Talmud and of all our sacred literature.

Moreover, as the modern Orthodox Rabbi Yitz Greenberg teaches in the pages of this book, the American Jewish community needs as large a tent as possible, and it needs to model civil conversations on difficult topics. We do not have the luxury of kicking people to the curb.

To quote Felicia Herman, Maimonides Fund COO and the managing editor of “Sapir Journal”: “You can’t have big and bold ideas if people can’t say what they think.”

To quote the “Rabbis’ Letter,” a missive on the subject of open dialogue, sponsored by the Jewish Institute of Liberal Values: “We all need space to be tentative, to be wrong and change our minds, to wonder, to explore.”

David Bernstein’s book will raise eyebrows and stimulate conversation.

That defines the Jewish world in which I want to live. I want to live in a Jewish community in which I might not agree with you, but at the end of the day — or, at the end of the week — I will still be welcome at your Shabbat table.

Which would be the very meaning of Shabbat shalom.