(RNS) — David Crosby was responsible for my first lesson in the Hebrew Bible.

Well, actually, it wasn’t just David Crosby. It would have been all of the Byrds.

I was 11 years old, and I had just bought their hit single “Turn Turn Turn.”

The label on the disc said: “Words and music by Pete Seeger, based on the book of Ecclesiastes.”

I asked my mother: “What is the book of Ecclesiastes?”

“Ah,” she replied.

With that, she went to a bookshelf and got down her old confirmation Bible. We found the Book of Ecclesiastes in its “back pages” (as in, the song by Bob Dylan, which the Byrds also recorded, and brilliantly), and there we found the words: “To everything there is a season, and a time for every purpose under heaven.”

Many years later, I would hear the Byrds’ leader, Roger (nee Jim) McGuinn in concert, and I had the chance to meet him.

Roger is a born-again Christian, and he has profound respect for Judaism. I told him I was a rabbi, and I told him the story of my childhood encounter with the real lyrics of “Turn Turn Turn.”

“That was my first Bible lesson,” I said. To which he responded: “And that’s not even in the Torah!”

He signed his autograph to me: “To Rabbi Salkin, your rabbi, Roger McGuinn.”

But “Turn Turn Turn” could not have existed without David Crosby’s sublime harmonies. Those harmonies came to define the Byrds — that, and their futuristic worldview, among other things.

The Byrds became my favorite rock band of all time — yes, surpassing the Beatles.

I saw them in concert several times. The best and most memorable concert was in 1971. It was at the old Music Inn (also sometimes called the Music Barn) in Lenox, Massachusetts. Apparently, their music was too loud, and it was drowning out the more dulcet tones of the classical music concert down the road at Tanglewood. The local police came on stage to get the band to turn down the amplifiers.

We audience members broke into wild applause when we noticed that one of the policemen was the Stockbridge chief of police, William Obanhein — aka “Officer Obie” of “Alice’s Restaurant” fame.

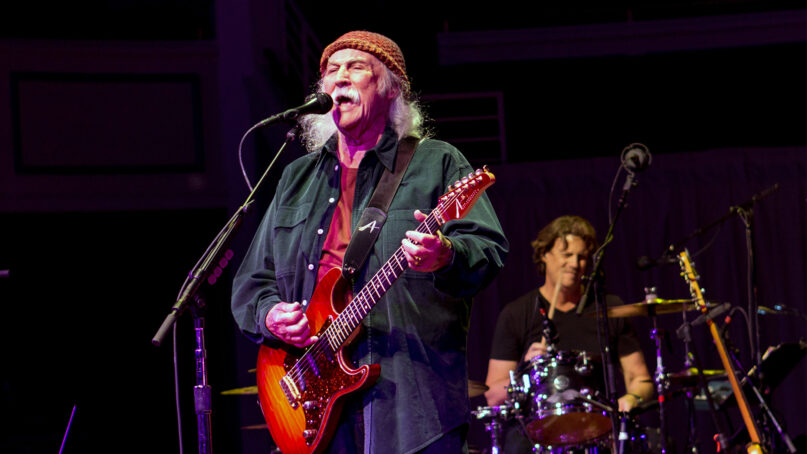

I stuck with David Crosby for his prodigious post-Byrds career, in various combinations with Stills, Nash and Young, and for his solo career as well. Throughout it all, there was his gorgeous voice, his unparalleled harmonies, his unique guitar style (he was one of rock music’s pioneers of alternate guitar tunings, a style Joni Mitchell also adapted) — and always, what seemed from afar, like a gentle and generous soul.

This, despite his troubled life, and his outlaw ways.

That is why I mourn his death, at the age of 81.

Eighty-one.

As you know, I am a rabbi, and I officiate at many funerals. I always read the Psalm that includes these words: “The days of our years are three score and ten, or by reason of strength, four score years.” Many of those funerals are for people who are the same age as David Crosby — four score years — and even a little younger.

Consider the fabled 27 Club of rock musicians — rock stars who died at the age of 27. That necrology includes Jim Morrison, Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, Kurt Cobain, Amy Winehouse and Brian Jones.

All of them, in the words of the poet laureate of the Jewish people H.N. Bialik, died “before their time, and before anyone’s time … with one more song within them.”

For all his challenges, David Crosby lived to be triple that age — surpassing the Psalmist’s “four score years.”

We can say to our aging rock icons, and perhaps to ourselves, in the words of Blue Oyster Cult, “Don’t fear the reaper.”

But, the coming of the reaper is inevitable — as sure as the late Warren Zevon asked his loved ones to “keep me in your heart for a while” and the late Leonard Cohen said to God “hineini — I’m ready, my Lord.”

Consider this mix of some of David’s later work. He stayed productive and creative. We were lucky to have had him for as long as we did.

Every year on Sukkot, when I reopen and relearn the words of the Book of Ecclesiastes, I always hear the Byrds singing its words. (Or, this version, with Bruce Springsteen and Roger McGuinn, which is one of my favorites).

This is, after all, the soundtrack of our youth, and when we lose a voice that was an essential part of that soundtrack, we are not only saying kaddish for the singer.

We are saying kaddish for our youth, as well.

Go in peace, David.