(RNS) — The sun crests in the northern sky on Wednesday (June 21), giving us the longest day of the year and marking the beginning of summer.

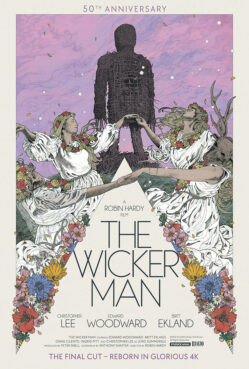

For a certain brand of pagan — oh, and horror fans — this year’s solstice also brings with it a much anticipated special theatrical rerelease of the 1973 classic British horror movie “The Wicker Man.” In anticipation of its 50th anniversary, the landmark film was reedited as a so-called director’s cut (its director, Robin Hardy, died in 2016) and given a high-quality 4K video face-lift.

Though set around May Day, or Beltane, the pagan holiday depicted in the film, the British full theatrical release was saved for the solstice, another of the eight sabbats on the Pagan Wheel of the Year. (It will be available in the United States in September.)

“The Wicker Man,” a folk horror set in rural Scotland’s isolated communities, is full of pagan religious ritual and folklore. The film was mostly panned upon its release but has since gained a cult following, aided by praise from film scholars, horror fans and modern pagans alike. Horror veteran actor Christopher Lee, who stars in the role of Lord Summerisle, considered “The Wicker Man” his best film.

A poster for the 50th anniversary release of “The Wicker Man.” Courtesy image

The film tells the story of Neil Howie (Edward Woodward), a police officer and devout Christian, who visits a remote island to investigate the disappearance of a young girl. While on the island, he uncovers a tight-knit, nature-based community that has fully rejected Christianity in favor of a folk-based paganism led by Lord Summerisle.

Wiccan high priestess Vivianne Crowley saw the film in London in 1974. “I was just expecting a standard Hammer horror,” where the good Christians were fighting the “evil Satanists,” she said, referring to London’s Hammer studio that churned out horror flicks from the 1950s onward. At the time, Crowley had just begun her journey as a pagan.

Instead, she and her pagan friends were “astonished,” she recalled. “Suddenly paganism was out there and given a serious role in this movie even if some of the presentations weren’t particularly positive.” Word spread quickly in the community. There was a later disproven rumor that Britt Ekland’s body double was a coven member, Crowley said, laughing.

Despite the film’s disturbing ending (from any point of view), modern pagans were immediately enamored of its presentation of a utopian community based solely in pagan religious values and folk traditions.

Kristoffer Hughes, chief of Anglesey Druid Order, said the darker elements of the film do not bother him. Hughes has been an outspoken fan of “The Wicker Man” for decades. “There is an intelligence to the film” that prevents it from casting a harmful shadow on modern Druidry or other forms of paganism, despite its unsettling ending. It offers, among other things, a discussion on the meaning of sacrifice, he said.

The love affair with “The Wicker Man” has persisted, going far beyond modern pagans. Since 2008, British musician David Bramwell began staging popular “Sing-a-long Wicker Man” events, which include a film screening, live performances and cosplay.

But for modern pagans, there is something familiar in the film.

Though modern pagan practices have many origin stories, the most dominant traditions, including Wicca, find their roots in British folk culture. Those practices have survived for centuries alongside Christianity. “In some ways, it feels as if that process is incomplete,” explained Miranda Corcoran, a lecturer at University College Cork in Ireland and an expert on horror. It’s as if, she said, “the advent of Christianity just sort of paved over the pagan traditions with a surface sheen.”

Those little pagan elements, such as May Day, are still there, she said. “A lot of our ideas about (modern) paganism and authentic pagan rituals actually come from 19th-century upper-class anthropologists,” such as Scottish anthropologist Sir James Frazer, writer of “The Golden Bough.”

Hardy, director of “The Wicker Man,” mirrored this idea in planting the origins of Summerisle’s religion in the Victorian period.

“That is essentially what modern Wicca and neopaganism is,” she said, “it is a re-creation of pagan beliefs.”

Despite these parallels, the movie’s religious themes and representations are not easy to negotiate for pagans — or any viewer, for that matter. While the nature-loving pagans may not be evil satanists, they are not the heroes either. Nor, on the other hand, is the Christian officer, whose fundamentalism leads him into the breast, quite literally, of the Wicker Man.

Corcoran explains that the film presents a struggle between two factions of religious extremism: a manufactured pagan cult led by Lord Summerisle, himself an authoritarian leader, and a “rigid, fire and brimstone” form of Christianity that dismisses any other belief.

Actor Christopher Lee stars as Lord Summerisle in “The Wicker Man.” Photo © Rialto Pictures/ Studiocanal

“While paganism definitely comes across as deviant in some ways, there also is a sense that Christianity is not necessarily in a position to take its place,” she said. The theme was common in British and American films of the time, expressing both the fear and a fascination with new religious movements as well as a rejection of conservative Christian values.

Corcoran believes that 50 years later these religious themes will still resonate. Although fears of new religious movements and cults are not nearly as pronounced, she said, there is a definite growing anxiety around “the authoritarian use of religion.” And the fear of the so-called deviant cult still prevails, as shown in the more recent folk horror film “Midsommar.”

Ashleigh Smiley agrees that the film still resonates today, even with younger American pagans like herself.

“There’s something nice about seeing people who are like you portrayed as a majority, even if they do something terrible in the end,” she said.

But, Smiley added, “I think the landscape of what it means to be pagan is always changing.” Will younger pagans be horrified by this film? Or find it humorous?

There is still “beauty among the horror,” Smiley said.