Wooden figurines of the Wiccan divine couple. Photo via Etsy

(RNS) — The Great Rite, a Wiccan ritual celebrating the creative union of the masculine and feminine, commonly occurs after a priest and a priestess call in the God and the Goddess, the Earth-based tradition’s co-equal deities, and after the main body of the ritual. Those attending are often standing in a circle, alternating by gender, as a ritual knife, sometimes called an athame, is dipped into a chalice or cup.

When Wicca, the best-known modern pagan religion and one that informs many others, was first established amid a revival of interest in the occult in England and the U.S. in the mid-20th century, it found a comfortable place among feminists for its equal celebration of a female deity alongside a male one.

Steve Kenson, co-founder of the Temple of Witchcraft in New Hampshire, called the introduction of the Goddess “revolutionary.”

Steve Kenson. Submitted photo

“It drew a lot of people to Wicca and to witchcraft, because it was an opportunity for women and feminine people to see themselves in the divine,” said Kenson, adding that the male-female binary also reflected the theological importance of polarity and a needed balance of opposing forces.

But the attention to the two sexes has presented problems for Wiccans proud of the religion’s progressive framework, as its reliance on gender binaries in both practice and belief has seemed to exclude LGBTQ+ individuals.

Since the birth of modern paganism, queer men otherwise attracted to the path for its alternative to traditional religion and acceptance among Wicca’s practitioners have had to overcome a certain amount of “erasure” inherent in its gendered assumptions.

In 1977, the Minoan Brotherhood was formed to counter what many queer men experienced as “erasure” by the “heterosexist culture of most forms of Traditional Witchcraft prevalent in the 1970s,” according to its website.

The sense of invisibility was not limited to queer men. Strict adherence to gender polarity “put me off early on,” said Ariana Serpentine, a witch and trans activist.

Ariana Serpentine. Submitted photo

Serpentine began her journey as a witch in the 1990s, and despite the gendered nature of Wicca, she “found an expression of spirituality and connection, especially to the Goddess, that was transformative.”

But by 2000, Serpentine had left the group and co-founded a new group that was less dependent on traditional gender binaries. There were “leaders” instead of priests or priestesses. People stood in ritual circle wherever they wanted.

Similar changes were going on across the greater pagan community. The Minoan Brotherhood, eventually joined by the corresponding Minoan Sisterhood, thrived along with other new queer-centered groups. Matraeum of Cybele, established in 1998 in New York, fostered an environment of radical inclusivity. Between the Worlds, founded in 2002, began offering a weekend event of community and ritual for queer men.

Increasingly, Wiccan and other pagan groups have adapted their ritual language and processes to meet the needs of their diverse membership.

At the Temple of Witchcraft, where Kenson runs the Queer Spirit Ministry, nongendered terminology such as “siblings” has replaced “brothers and sisters,” and in rituals three divine aspects are called upon: divine masculine, divine feminine, queer spirit. In performing the Great Rite, there is a new focus on union, such as “our union with the divine,” or “the union of our three souls.”

Kenson believes the magic, rituals and the spiritual work are not diminished by the adaptations.

The Temple of Witchcraft marching group at Boston Pride for the People 2023. Photo courtesy of Steve Kenson

Many queer-identifying pagans have started working with deities whose stories challenge gender binaries — the Norse god Loki, the Greek god Dionysus, the Phrygia goddess Kybele and others.

“I also see there is also a shift in thinking about it too,” Serpentine explained. If deities are “cosmic beings on some level, the question of what their gender is,” especially if gender is a human construct, is up in the air, she said.

“We assign gender to deities,” Serpentine said, and many of those assignments were made a long time ago. There are increasing opportunities and spaces to challenge those assumptions. “Many people experience deities in cross-gendered ways,” she added.

The move to inclusiveness has made paganism “safe and safer,” Serpentine said, “more comfortable.”

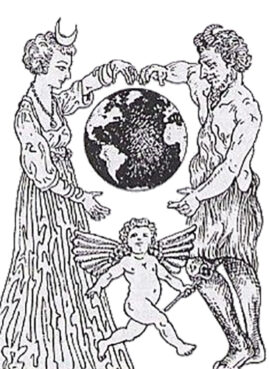

The divine couple in Wicca, with the Lady as Hecate, left, the witchcraft goddess, and the Lord as Pan, the horned god of the wild Earth. The lower figure is Mercury or Hermes, the god or divine force of magic. Image courtesy of Wikipedia/Creative Commons

But some pagans are resisting the changes. Covens that choose not to adapt may see initiates “hive off” or branch off to establish more inclusive group practices, said Janine Nelson Hoffman, a Wiccan elder high priestess who serves on the board of the Covenant of the Goddess, a national organization of Wiccans and witches. Hoffman’s own coven is already making changes, she added, and she has served in the roles of both priest and priestess.

In a decentralized religion, this is how change happens, Hoffman explained. The process is slow, dynamic and highly organic.

Serpentine, however, believes that the adaptation process should be more direct and counsels pagans not to wait until a queer-identifying person first joins the group to begin the conversation.

“Trans, nonbinary, lesbian and gay people are part of humanity. If you are excluding us, if you are excluding our experiences from your spirituality,” she said, “I don’t believe your spirituality can be whole because you are excluding part of humanity.”

This coverage is presented with the support of the E. Rhodes and Leona B. Carpenter Foundation.