It is time for us to talk about one of the greatest problems that exists between people – and that is the issue of the grudge.

Here is something that you might have noticed. There is a grammar of grudges. You don’t simply have a grudge. You bear a grudge. You carry a grudge.

Sometimes, we carry those grudges from generation to generation. We carry them through our families. They become the poison ivy that grows on the family tree.

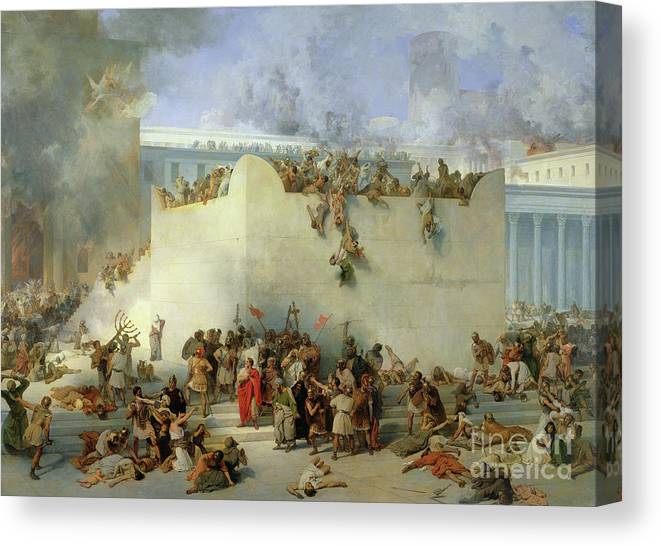

The grudge is like a sacred text — like, for example, the book of Lamentations that Jews read today, on Tisha B’Av, commemoration of the destruction of the temples in Jerusalem. We take that book of grudges off the shelf, and we chant from it, with our own invented melodies.

How bad can grudges get? Do you really want to know?

Let’s talk about today — about Tisha B’Av.

Last week, I was at the Arch of Titus in Rome. When I was there, I meditated on the meaning of the destruction and our subsequent exile — while making some snarky comments to the imaginary Titus: “Ha ha. We, the Jews, are alive!”

But, the other day, I was back in Rome, and I walked past the Arch of Titus again — and my mind went elsewhere.

Why did the Romans decided to destroy ancient Judea?

Historians would supply the following answer. Ancient Judea was a far corner of the Roman Empire. The Jews rebelled against Rome, and so the Romans put down the rebellion. They did the same thing in Britain. They did the same thing in Gaul. They did the same thing in Germania. No big deal.

But that is not the way that ancient Jews told the story.

No — it had to be our fault. That’s how we Jews roll.

In the Talmud (Gittin 55-56), we find the following story.

Back in the first century, when Rome occupied the land of Israel, a rich Jew in Jerusalem was having a huge party – a major catered affair. He sent his servant to invite a man named Kamza to the party.

The servant made an error. He screwed up the name of the person he was supposed to invite. He was supposed to invite a man named Kamza. Instead, he invited a man named Bar Kamza.

It is like saying: Invite Levine to the party. But instead, you make a mistake, and you invite Levin. Or, LaVigne.

But here was the problem. For years, the host of the party had been bearing a grudge against Bar Kamza.

So, the night of the big party arrives. Bar Kamza shows up. With a bottle of wine. And a box of rugelach.

The rich man tells Bar Kamza to get out of his house, and to leave his party.

“Please, let me stay,” Bar Kamza begs. “I know that this was a mistake, but I only ask that you don’t humiliate me in front of all your guests.”

“No, you have to leave.”

“Please, let me stay. I will pay for my share of the dinner. Whatever I eat, I will pay for. Just don’t humiliate me in front of all your guests.”

“No, get out.”

“Look, I will pick up the bill for the entire party – everything – the food, the flowers, the band, the chocolate fountain — everything! Just don’t throw me out in front of everyone. Don’t humiliate me!”

But the host refused, and he threw Bar Kamza out into the street.

Bar Kamza was so angry that he did not forget what had happened.

Bar Kamza was hurt and humiliated and he was deeply furious – and not only at the host.

Because do you know who else was at the party?

All of the sages and rabbis of Jerusalem! They were all sitting there. They saw what was happening. They said nothing. They let him be humiliated.

What did Bar Kamza do?

He went to the Roman authorities. He told them a lie. He told them that the Jews were plotting against them.

Because of that, the Romans attacked Jerusalem; we lost our independence; we went into exile for two thousand years.

All because a rich man was graceless. And all because another man could not let it go.

Years ago, I counseled a woman who had just lost her mother. Her mother was a deeply problematic person. She had been both emotionally and physically abusive to her daughter.

As you can well imagine, the bereaved daughter was having a rough time.

“I can’t let it go!” she cried to me at shiva. “I cannot forgive her for what she did to me!”

This is what I said to her.

“I don’t know that you are ever going to be able to totally let it go. That might be a super-human feat. But if you keep this anger in the front of your being, you are giving your mother total power over you, even in the grave. You can continue being angry with her, but that anger can no longer harm her. It can only harm you.”

F. Scott Fitzgerald once said: “Living well is the best revenge.”

I would prefer to put it is a slightly different way. Living whole is the best revenge.

Now, how do you live whole?

In Jewish folklore, there is the angel, Purah — the angel of forgetfulness.

Once, there was a man who remembered everything that he had seen or heard. But, if someone sinned against him, and if that person then came to him and asked for forgiveness, Purah, the angel of amnesia, would place her hands on his head — and he would forgive that person – and he would forget everything bad that had happened.

Is this even possible? To forgive, perhaps. But, to forget.

It might not be possible, which is precisely why it takes an angel to make it happen.

For years, I have spent too much time at airport baggage carousels. During those times when I have been waiting for my bags, I have sometimes meditated on the sign that says: “Check baggage carefully. All bags look alike.”

For some baggage, when you get to the end of your journey — it is better off to simply leave it on the conveyor belt.

For those Jews who are fasting today, may it be a meaningful fast.

I am going on a grudge fast, as well.