(RNS) — For all its faults, religion has in many times and places had an equalizing and democratizing effect on society. If houses of worship were not beacons of diversity, faith at least provided a place and a common language, for young and old, rich and poor, conservative and liberal. Social distinctions carried over into the pews, of course, but all had come for the ordered worship of Almighty God, who saw us all as one.

Nowhere was this more true than the American working class in the mid-20th century. Northeastern Catholics who labored all week packed the kids into the family car and headed to Mass. Congregations in farm communities came together at church to form tight-knit, mutually supporting communities. Southerners most of all, Black and white, rich and poor, put on their Sunday best and went to church.

Those days are over. Religion is the province of the better-off in America. The anecdotal evidence is in the parking lots of churches in nearly any part of this country. You can see it by the quality of the cars.

Increasingly, we have data to prove it. Religious demographer Ryan Burge insightfully and provocatively drew attention to this fact last month with a report declaring, “Religion has become a luxury good.”

Harnessing years’ worth of data from the Cooperative Election Survey, Burge shows that weekly attendance at church is correlated with higher levels of educational attainment and higher incomes. On the other hand, the share of Americans identifying as “atheist, agnostic, or nothing in particular” — the much discussed religious “nones” — is highest among the least educated and lowest among those with post-graduate degrees.

The trend does not hold at the very highest levels of income and education. People with doctoral degrees identify as nones (24%) at higher rates than people with master’s degrees (20%). Attendance drops off as college educated households’ incomes approach $200,000 or more.

In this sense, despite Burge’s characterization, religion seems more like a new SUV or minivan than a Bentley or a Maserati, more a big house in a nice suburb than a vacation home in the Hamptons or Palm Springs. The actual luxury class is much less interested in religion than the middle class. And the working class is least interested of all.

The question why is hard to answer. Some prosperity gospelers might try to convince you that strivers become winners because they go to church. Perhaps people go to church because they are striving and winning.

We know it’s not a matter of cost: Anyone can afford to go to church. But one answer might be that other things that correlate with lower income levels don’t match up with religious participation. People who work weekends, have erratic work schedules or multiple jobs might not be able to make it to services, or simply not have the energy.

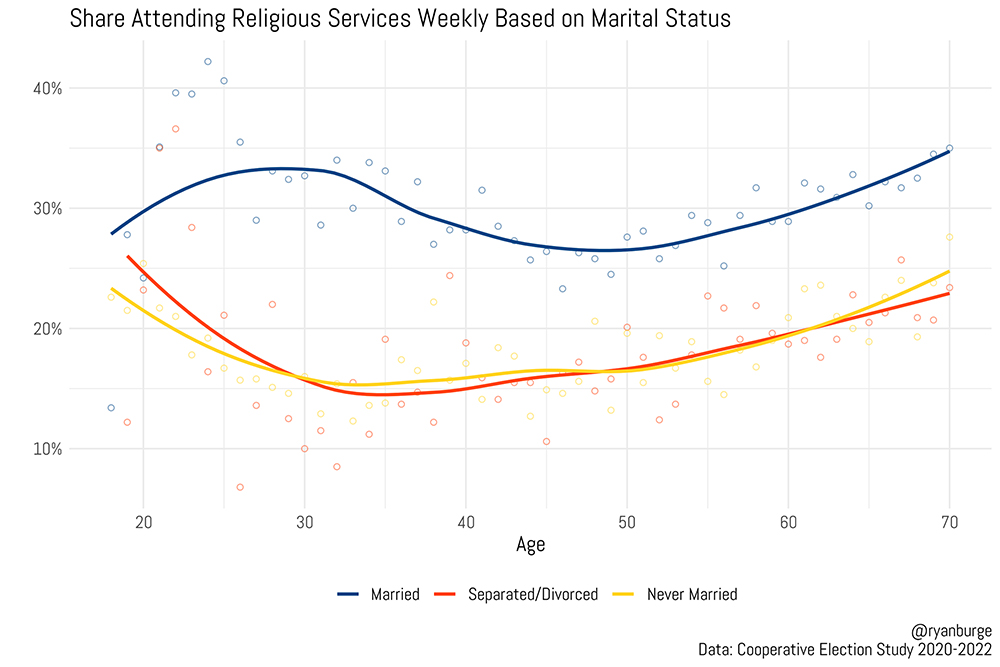

“Share Attending Religious Services Weekly Based on Marital Status” Graphic courtesy Ryan Burge

But another clue is that married survey respondents are significantly likelier to report weekly attendance than the separated, divorced or never married. Unsurprisingly, married parents in every age cohort attend services more regularly than non-parents. At age 30, fully 37% of married parents report weekly attendance, compared with 22% of married non-parents. Attendance for unmarried adults age 25-50 hovers between 10% and 20% whether they have children or not.

The pattern, Burge points out, is unmistakable: More than anyone else, religion is for Americans who did everything “right:” pursued higher education, found a good job, got (and stayed) married and had children. People whose lives took another turn are significantly less likely to participate.

A lapsed Christian myself, I have a theory that many of my cohort have accepted the assumption that faith is for people who have it all together. Many religiously unaffiliated, who, after all, are not primarily agnostics or atheists, simply take the position, “I’ll go (back) to church once I’ve gotten my life together.”

I also suspect that couplehood has a lot to do with it. Most people understand Christianity to teach fidelity in marriage and chastity in singleness. While taboos against premarital sex and cohabitation are only rarely in place any longer, most people have an intuition based on their sexual reality whether or not church is a place for them.

More than this, church life is often oriented toward married couples, with children who fill up education programs. Marriage rates are plummeting, especially among the working classes.

In sum, people may say they don’t have time, but it may also be that they think their social standing makes them misfits.

If religion is to ever again be a unifying, uplifting, democratizing or equalizing force in our society, the people who are not (yet) strivers or winners will need to feel welcome and believe there’s a compelling reason to participate. That seems to be where the church has failed.

Burge, reminding us of the old adage that good preaching should comfort the afflicted and afflict the comfortable, concludes that the church should afflict the comfortable, its core constituency, more. Indeed, congregations must be more than a chaplaincy for the country-club, private-school and professional-class set.

Jacob Lupfer. Photo by Kit Doyle

But following Pope Francis’ admonition that the church be a field hospital for sick and wounded souls, it seems to me congregations should focus on comforting the afflicted, of whom there are many, increasingly estranged from our faith communities.

(Jacob Lupfer is a writer in Jacksonville, Florida. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)