I am going to propose a new Academy Awards category.

“Most prodigious consumption of nicotine in a major motion picture.”

“Golda” would win. Hands down.

The first visual image in “Golda” is a cigarette in the hands, and on the lips, of Golda Meir — Israel’s first, and to this day, only woman Prime Minister. Golda Meir was an inveterate chain smoker – lighting one cigarette off another one, even smoking during medical procedures. The movie features numerous still life shots of overflowing ash trays. You can almost smell it.

But, smoke is not just about cigarettes. It is a metaphor — the smoke from the chimneys of Auschwitz; the smoke on the battlefield; the haze of war.

There is no question. “Golda” is a triumph of a movie. The movie is part of a small cultural phenomenon that I have nicknamed “Goldamania.” Golda Meir is not only the subject of this movie, but of two biographies that capture and re-evaluate her life and contributions to the history of Israel, and beyond that, to the world: “The Only Woman in the Room: Golda Meir and Her Path to Power,” by Pnina Lahav, and “Golda Meir: Israel’s Matriarch,” by Deborah Lipstadt.

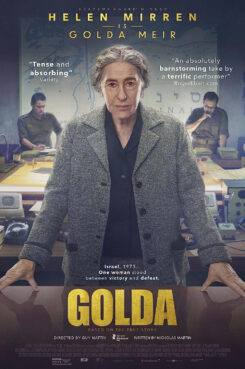

“Golda” film poster. Image courtesy Bleecker Street

Helen Mirren is spectacular, delivering an Oscar-worthy performance. She is clearly at her best when she plays powerful women, as she did as Queen Elizabeth I and Queen Elizabeth II. But, her performance as Golda Meir is the most complex of them all, if only because Golda was, herself, the most complex of them all.

The other performances are just as good. Rami Heuberger plays an emotionally conflicted Moshe Dayan (quite different from his usual impenetrable macho image). Liev Scheiber is a very credible Secretary of State Henry Kissinger; his physical resemblance is wonderful, and he nails Kissinger’s accent.

“Golda” brings us through the Yom Kippur War of 1973, and PM Meir’s role in that war.

I remember it well. The Six Day War of 1967 happened during my bar mitzvah year. But, in terms of my own Jewish identity, the Yom Kippur War was my true coming of age.

On Yom Kippur, 1973, I was a college sophomore at SUNY Purchase. My parents had called me that morning to tell me about the attack. I was walking to the dorm parking lot, on my way to services at a local synagogue.

A fellow student saw me. He noticed the expression on my face, and he asked me: “Why do you look so sad?” I answered him: “The Arab armies have just attacked Israel, and today is Yom Kippur.”

He answered me with words that I shall never forget. “How are we doing?” I had not known that he was Jewish, but that “we” went straight to my gut.

He continued: “Those bastards…”

He knew what I knew. The Arabs had timed their attack to take advantage of Israel’s strategic weakness on the holiest day of the calendar. They were continuing a demonic tradition — scheduling antisemitic assaults on the sacred days of the Jewish calendar. They wanted to deliberately and forever profane those days in Jewish memory.

The Yom Kippur War was a watershed moment for me. It awakened me to the plight of the Jewish state, and by extension, the Jewish people. It was also my first real taste of the anti-Israelism of the far Left, which I encountered on campus, from students and faculty alike. In many ways, the Yom Kippur War propelled me towards my career choice of the rabbinate.

But, here is what I did not know, and what many of us had forgotten.

In his recently released memoir, Martin Peretz, the former publisher and editor of the New Republic, reminisces about those dark times. He recalls his conversation with Simcha Dinitz, Israel’s ambassador to the United States, on the second day of the war.

Martin Peretz’s words: “I trusted Simcha never to tell me something that wasn’t true. All he said was: ‘Everything is at stake.’”

“Everything is at stake.” The situation was dire. Israeli military leaders used apocalyptic terms like “Armageddon.” They predicted another Masada. That was what Golda knew when she told her aide: “If the Arabs reach Tel Aviv, I will not be taken alive.”

She was preparing to follow in the footsteps of the zealots at the top of Masada. She was prepared to commit suicide.

So why this movie, and why now?

Helen Mirren as Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir in “Golda.” Photo courtesy Bleecker Street

First: The audience members of “Golda” (most of whom will not be Jews, and many of whom will not be familiar with Israel) will enjoy a two hour primer on Israel’s history. They will understand how vulnerable Israel was, and how vulnerable Israel still is. It’s called Iran.

In the movie, Golda tells Moshe Dayan that he needs to address the nation. “Reassure the people, and then teach our enemies a lesson they’ll never forget.” Harsh words, and necessary words. Israel cannot afford to lose a single war.

Second: “Everything is at stake.” Simcha Dinitz’s words echo today.

In 1973, what was at stake? Israel’s security.

In 2023, fifty years later, what is at stake? Israel’s soul, the vision of Israel as a state that enshrines democratic values. That is why demonstrators are going into the streets.

Third: There is a lesson for American Jews.

One of my favorite scenes is a reprise of a famous historical moment. Henry Kissinger reminds Golda about his limitations in helping Israel get necessary armaments from the United States.

“Golda, you must remember that first, I am an American; second, I am Secretary of State; and third, I am a Jew.”

To which Golda responded: “Henry, you forget that in Israel we read from right to left.”

The lesson: Don’t erase yourself as a Jew.

Finally, the movie’s bookends.

The movie begins — yes, with cigarette smoke — but also with a newsreel reference to the Six Day War of 1967, and the plight of Palestinian refugees. In that sense, the Six Day War still continues.

The movie ends — on a note of hope. Golda had demanded direct talks with the Egyptian President Anwar Sadat. Moreover, she had demanded that he refer to the Jewish state as Israel, and not merely the Zionist entity.

She got her demand.

We see historical footage of Golda and Sadat meeting each other when he came to Israel in 1977. She bought a gift for his new grandchild, as an offering of a grandmother to a grandfather.

How utterly powerful she was — flawed, but decisive — and how utterly human she was as well. She was steely, almost like Churchill in the dark days of the Blitz during World War Two.

But, she was vulnerable — profoundly so — as when the tears of a recently bereaved mother move her to tears, as well.

That is why she is eternally “Golda,” and not “Prime Minister Meir.” (I have always loved the Israeli penchant for calling politicians by their nicknames. It speaks of an intimacy of being a small people, but a large family).

But, the movie really ends with something else.

During the final credits, we hear the late Leonard Cohen singing “Who By Fire?” It is his re-working of the Yom Kippur liturgy.

This is one of the most rumored, and most fascinating chapters in the history of rock music. Matti Friedman tells the story, poignantly and powerful, in his book “Who By Fire: Leonard Cohen in the Sinai.”

Cohen’s musical career was at a lull. When war broke out, he left the Greek island of Hydra and traveled to Tel Aviv. There, he was spotted in a coffee shop and recruited to come to the Sinai to entertain Israeli soldiers. Leonard emerged from his time in Israel with a new sense of purpose, and a new collection of powerful songs that have more than stood the test of time.

Matti writes about what it was like for Leonard to be with those Israeli soldiers:

Some of the men on the sand look up at the visitor with his guitar. Others look down at their dirty knees and boots. Cigarettes glow in the dark. The heat has broken and the desert is still for now. They’ve been fighting for fourteen days and no one knows how many days are left, or how many of them will be left when it’s over. There aren’t any generals or heroes here. It’s just a small unit getting smaller. In the wastelands around them, thousands of Egyptians and Israelis are dead.

He introduces the next number. “This song is one that should be heard at home, in a warm room with a drink and a woman you love,” he says. “I hope you all find yourselves in that situation soon.” He plays “Suzanne.” The men are quiet. They hear about a place that doesn’t have blackened tanks and figures lying still in charred coveralls. It’s a city by a river, a perfect body, tea and oranges all the way from China. “They’re listening to his music,” writes the reporter, “but who knows where their thoughts are wandering.”

It is fifty years later, and my thoughts still wander back to those days — those days that shook me, and stirred me, and made me the Jew I am today.

I am unembarrassed to say: I cried during “Golda.”

You will, as well. This is the perfect movie to see as we enter the season of the Days of Awe.