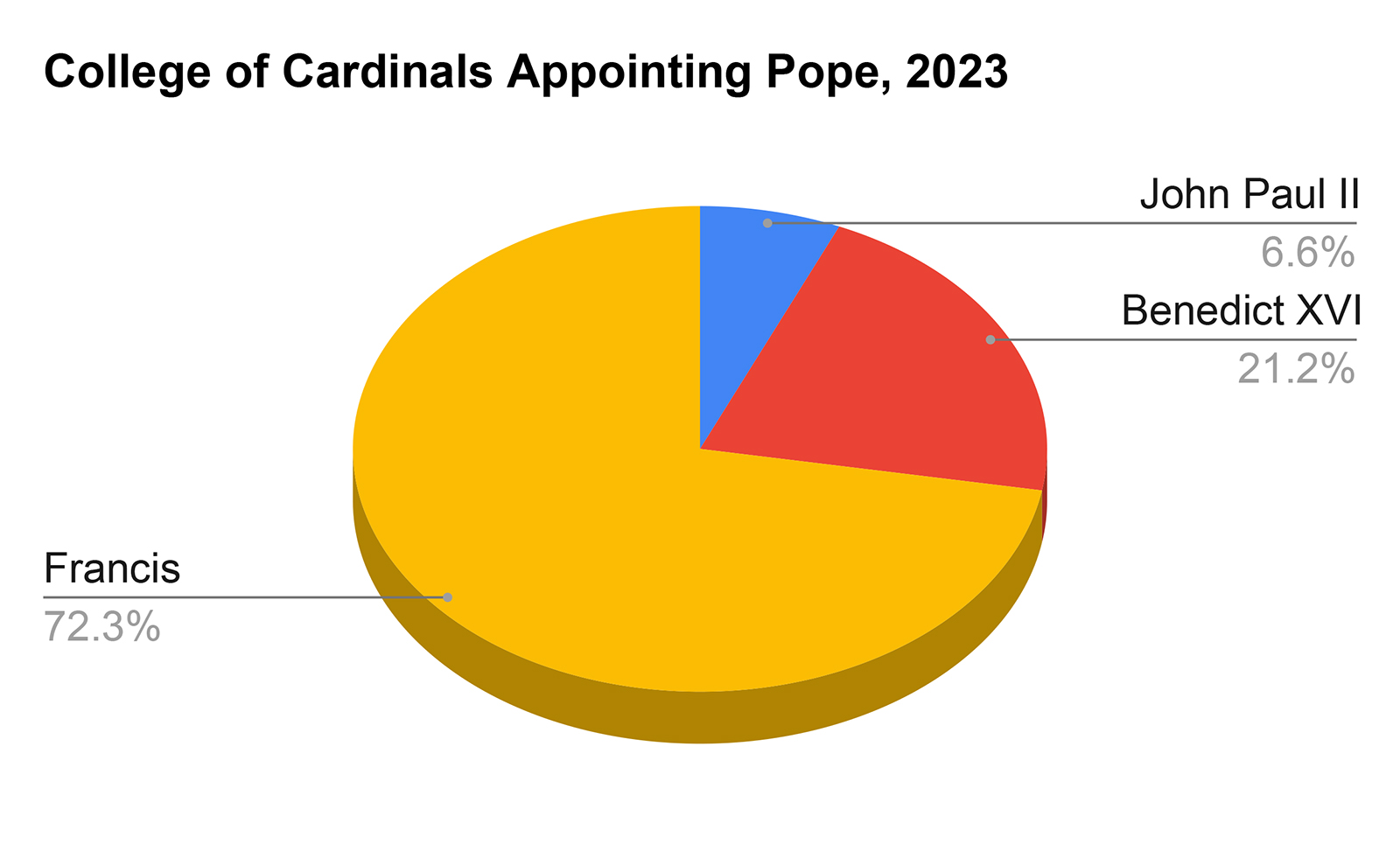

(RNS) — By the end of the day on Sept. 30, Pope Francis will have crossed an important threshold: He will have appointed enough cardinals to have created a supermajority at the next conclave, the gathering of cardinals that will select his successor.

Taken at face value, Francis’ statistical watershed suggests he has ensured that the next pope will share his style and vision. But the reality is far more complex. History shows that conclaves exercise a logic of their own that owes little to the pope who devised them.

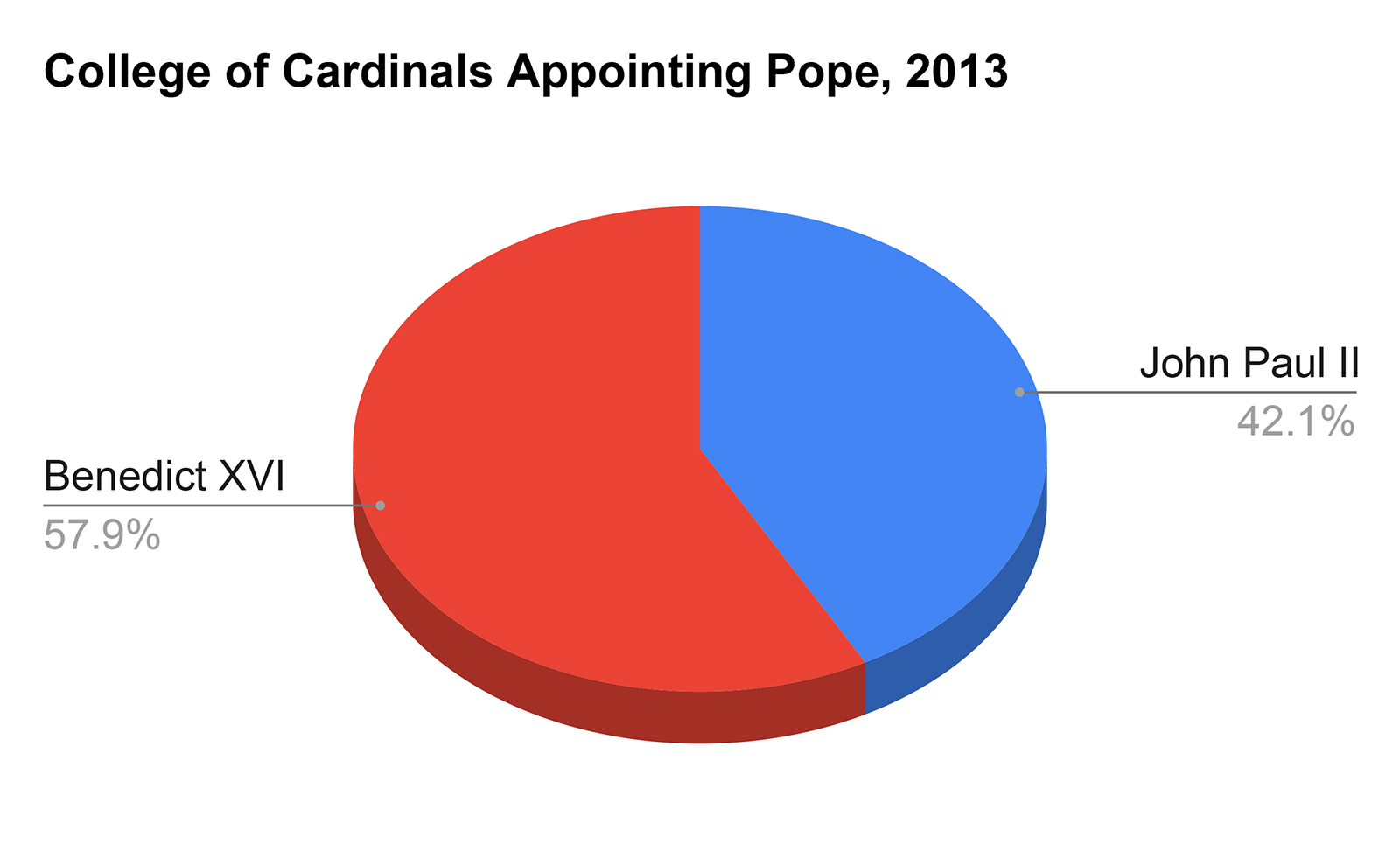

After all, Francis, who is seen as a liberal reformer, was elected by a conclave for the most part assembled by Popes Benedict XVI and John Paul II, both staunch conservatives.

“The next pope won’t necessarily share his views with Francis 100%,” said Massimo Borghesi, a philosopher at the University of Perugia and author of “The Mind of Pope Francis: Jorge Mario Bergoglio’s Intellectual Journey,” in a recent interview. The next pope is likely to respect Francis’ bent for dialogue and “a missionary approach,” Borghesi said, but the conclave is likely to consider other qualities as important, and many factors will decide who is chosen.

“College of Cardinals Appointing Pope, 2013” Sources: Publicly available Vatican data, Wikipedia, independent RNS reporting. RNS graphic

Speculation about the next pope is still relatively quiet: Francis remains mentally present as ever, and though he shows signs of his age, 86, he isn’t evidently ill. But papal succession is a constant conversation at the Vatican, no matter the health of the current pope, and even Francis is in on it. After a tiring visit to Mongolia in early September, the pontiff quipped that if he wouldn’t return to the Central Asian country himself, then “surely John XXIV will go.” (The previous pope named John was the 23rd.)

But if papal prognosticators are always busy, their job has become even harder under Francis. The reforms he has made, particularly his determination to clean up the Vatican’s historically corrupted finances, has reduced the influence of anyone tainted by scandal.

As secretary of state, Cardinal Pietro Parolin, 68, is the highest-ranking prelate at the Vatican after Francis, and, combining Francis’ vision with an Italian flair and diplomatic savoir faire, he was considered an obvious candidate for pope. But after his department got tangled in a failed real estate deal, Francis stripped the secretariat of its financial assets, and Parolin now looks diminished. Formerly the third highest ranking Vatican prelate, Cardinal Antonio Becciu is on trial for fraud in the real estate case and he has alleged that the fallout cost him his shot at the papacy.

Others have risen and fallen in Francis’ bureaucratic shuffles. Ghanaian Cardinal Peter Turkson, 74, was removed from his influential position as prefect of Integral Human Development in favor of Cardinal Michal Czerny. Cardinal Angelo De Donatis received the red hat from Francis and was named Vicar of Rome, only to be marginalized. A papal favorite for his work leading the vibrant church in the Philippines, Cardinal Luis Tagle lost his job running the global charity network Caritas Internationalis.

Given the excitement that Francis has generated in and outside the church, the conclave may well draw the next pope from among Francis’ closest collaborators, such as Cardinals Matteo Zuppi, Mario Grech or Cardinal Konrad Krajewski.

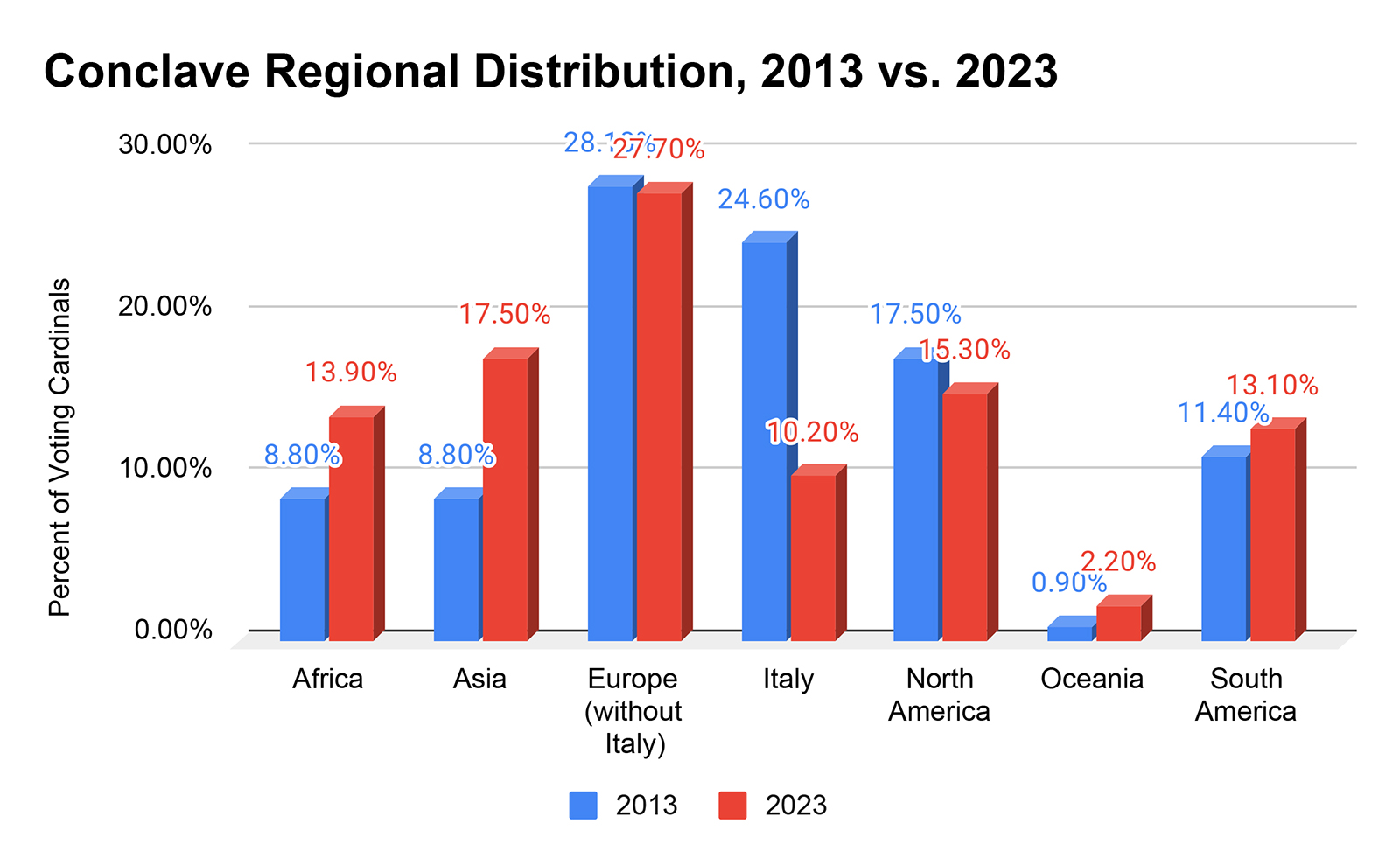

“Conclave Regional Distribution, 2013 vs. 2023” Sources: Publicly available Vatican data, Wikipedia, independent RNS reporting. RNS graphic

At 59, Krajewski, the papal almoner, has been responsible for some of Francis’ most headline-grabbing charitable acts, including helping bring transgender sex workers to the Vatican at the height of the pandemic. He has also made news of his own, jumping into the Roman sewers to restore electricity to an apartment inhabited by homeless people and blessing mass graves in Ukraine last year, leaving an impression that will be difficult to ignore at the next conclave.

Zuppi, 67, the head of the Italian bishops’ conference, has also come to prominence in the pope’s energetic diplomatic efforts. Francis tapped him to lead his delicate peace mission to put an end to the conflict in Ukraine, and he was the first cardinal to meet with Chinese authorities in Beijing. He can boast the support of the influential lay movement of Sant’Egidio, which has become a powerful element of the Vatican’s informal diplomacy.

Grech, who heads the Vatican’s synod office, oversees an effort Francis has infused with new energy, turning tired meetings of bishops summoned to strengthen Vatican pronouncements into dynamic encounters of Catholic clergy and lay people discussing the future of the church.

Grech will be a key player in next month’s Synod on Synodality, Francis’ project to reform the church’s culture, government and possibly even doctrine. The cardinal, who will also run the second meeting of the synod next year, is filling a role similar to that of Pope Paul VI, who, as Cardinal Giovanni Battista Montini, was active in the Second Vatican Council and brought it to completion after the death of Pope John XXIII.

Paul, an Italian who had served in the Vatican bureaucracy for 30 years before becoming archbishop of Milan, was elected by a conclave in which 36% of the voting members were Italians and became the 216th Italian to occupy the seat.

“College of Cardinals Appointing Pope, 2023” Sources: Publicly available Vatican data, Wikipedia, independent RNS reporting. RNS graphic

Today Italy has not had a pope for 45 years, and the number of Italian voting cardinals has diminished under Francis, falling from nearly a quarter of voting members at the 2013 conclave to about 11% today, as Francis has elected arguably the most geographically variegated college of cardinals in the history of the church. Places such as Burma and Mongolia have gotten their first red hats under Francis, giving Asia a representation of nearly 18% — double the share since Francis was elected. The diverse college may select a pope who can represent the global reality of the church.

But many of these far-flung cardinals have few opportunities to mingle with other cardinals to build a constituency at the next conclave and have gained little experience in the complex practical realities of the Vatican, a prerequisite to becoming an effective pope. And Europe still holds around 38% of the conclave’s voting seats and remains a force to be reckoned with.

The European bloc may rally to push through a dark horse from the progressive movement that has unsettled the church by pushing Francis’ drive for inclusiveness to its most liberal conclusions. Cardinal Reinhard Marx, 70, the archbishop of Munich, has had an influential role in the German Synodal Path, a conference of Catholic clergy and lay people in the country that has welcomed LGBTQ Catholics and is open to the ordination of women.

Pope Francis leaves after presiding over a consistory inside St. Peter’s Basilica, at the Vatican, Oct. 5, 2019. (AP Photo/Andrew Medichini)

But it is equally likely that conservatives will rally around such Francis critics as Cardinal Raymond Leo Burke, who has argued the upcoming synod could lead to schism, and convince other voting cardinals that the church needs to balance Francis’ tenure with a dose of traditionalism. They may get backing from the 19 cardinals from Africa who have a reputation of holding more conservative positions on doctrine and sexuality, while advocating strong social justice and reconciliation efforts. An African pope would likely restore the conservative ethic of John Paul and Benedict, while sending a powerful message of support to countries attempting to free themselves from the yoke of neocolonialism and help to fend off the new authoritarian incursion of Russia and China.

There are plenty of candidates, however, who would be seen as a middle path: Moderate cardinals from the church’s traditional European power center, such as French Cardinal Jean-Marc Aveline or Hungarian Cardinal Peter Erdo, 71, who has expressed vocal support for Francis while staying in sympathy with conservatives. The Luxembourg-born Cardinal Jean-Claude Hollerich, 65, has been an advocate for Francis’ synodal vision while drawing the line at Germany’s liberal propositions.

As many cardinals filter into Rome over the next days and weeks for the Synod on Synodality, the question of the next pope will no doubt be discussed in the formal and informal small groups of Spanish, French, Italian and English speakers from around the globe. Those from the church’s peripheries will have the chance to get acquainted with their Western counterparts, talk about their concerns and form alliances, cementing their hopes and bets on who will lead them next — or unsettling the picture once again.

This piece has been updated to clarify nations that received their first cardinals.