Remember the SAT exam? The vocabulary section?

Here is a word that might have appeared on that exam — or, perhaps on Will Shortz’ puzzle master program on Sunday mornings on National Public Radio.

The word is palimpsest.

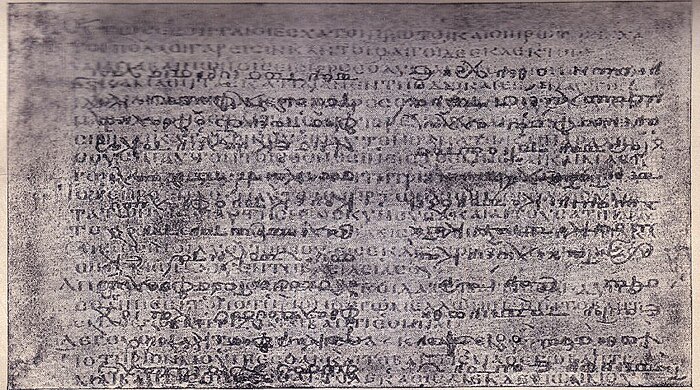

A palimpsest is a manuscript page, either from a scroll or a book. On that particular page, someone would have scraped off, or washed away, or in some way erased the written text in order to re-use that page to create another document.

Why did they do this? Because in ancient times, people wrote on parchment. Parchment was made of lamb, or calf, or kid skin. It was expensive. It was not readily available — so, in the interest of economy, they simply reused it.

The palimpsest also exists in art. It exists as (another SAT word) a pentimento. In a pentimento, artists would deliberately paint over earlier paintings that they had created. In a pentimento, you can still see the traces of those earlier images.

One of the most famous examples of a pentimento is Picasso’s “The Old Guitarist,” from his blue period, in which he painted over the image of a woman — again, because times were tight and materials were costly.

“Pentimento” is a wonderful word. It comes from the Italian word for “repentance,” because that is what repentance really is. It is when you see the images that you had once created for yourself, and your life, and you determine that those images no longer suit you, and you paint over them.

Because the artistry of the soul resembles the artistry of the painter. It is the ability to see the beauty, and to reclaim the beauty, even when it has been smudged over. For this reason, the word for artistry is omanut, and it is related to the word for faith, which is emunah. Artistry takes faith, and faith is a kind of artistry.

So, why is the word “palimpsest” relevant to us?

I discovered the importance of this word when I was preparing High Holy Day services for Congregational Emanuel in Redlands, California, with Cantor Jennifer Bern-Vogel.

There I was – sitting with the large, pulpit edition of the High Holy Day prayer book — the machzor, which comes from the word to return, as in: “I return to this text every year.”

As the Cantor and I were going through the musical cues, I noticed that my copy of the machzor contained numerous pencil markings and notations. Those markings go back at least eight years, for different congregations. Those markings consist of check marks, musical notations, arrows, asterisks, “skip to page 454.” They contain the names of congregants in those past congregations who had honors or reading parts.

I would re-read those names, and smile.

Or, in some cases – in far too many cases – I would grimace silently within myself, as I recalled that those people had died, and I realized that their names in the book were all that was left for me of their memories.

As the cantor and I went through the services for these days of awe, I erased those markings and wrote new markings.

I noticed that the pages were getting worn. Each page was like a literary archaeological dig, bearing the marks of past years and past services.

My machzor is a palimpsest, a document written upon and erased time and time again.

Yesterday was Yom Kippur, and I am obviously still there in my mind. The word kapar or kafar means “to make atonement.” When I was recently in Jerusalem, I encountered a slang phrase — Kaparah alecha/kaparah alayich. It literally means “atonement over you.” It means: You are my atonement. You are the sign that God has wiped away my previous sin.

It is a very nice thing to say to someone.

It might be the nicest thing that you can say to someone.

But, now I go to my scholarly books, and to my biblical dictionaries.

There, I discover that the original meaning of kapar or kafar was to cover over something.

For example, in the story of Noah, we read that the roof of the ark was kafar, covered over with pitch.

In the book of Exodus, we read about the design of the ancient tabernacle. The part of the tabernacle that covered the ark was the kaporet – the same word – kapar.

For it is not only that the master image during these Days of Awe is the Book of Life. It is time for us to confront exactly what goes into the creation of that Book of Life.

Once upon a time, I believed in the mythic notion that it is God Who writes our Book of Life for us, and that it is God Who inscribes our names in the Book of Life.

Now, as I reach this part of my journey, I am no longer so sure.

God is neither the author of our book of life; nor does the divine hand write that book of life (if you believe that God has a body, and therefore, has a hand).

We are the authors of our book of life. We write it, and we re-write it, every year. Every year, as I did with my High Holy Day machzor, the one that contains all the cues – we go through the cues that we have written in the book in past years, and we ask ourselves: Do those cues still work? Do they still make sense? We see the erasure marks from past years, and from this current year. We see what we have written, and what it is that we have had to revise.

It is never in ink.

It is always in pencil.

You can always erase it, and write over it, and write it anew.

Bachya ibn Pakuda was a sage who lived in Saragosa, in el-Andalus, what we would now call Spain, in the eleventh century. He was the author of the first Jewish system of ethics, which he wrote in Arabic around the year 1080 – which we know in Hebrew as Chovot HaLevavot, “The Duties of the Heart.”

These are his words.

“Our days are like scrolls – write on them what you want to be remembered.”

So, let us look with utter clarity at the old pencil marks in that book of life, the old cues, the old instructions. Do those old cues, those old instructions, those old ways – do they still serve us? Are those old stories still part of who we are?

And then, you will see your life as one long scroll, and you will write upon that scroll all that you want to be remembered.

(Adapted from my Yom Kippur sermon, delivered at Congregation Emanu El, Redlands, California)