(RNS) — Theology professor Grace Kao’s new book was inspired in part by a plotline from the sitcom “Friends.” Kao was watching an episode where Phoebe, one of the show’s main characters, agrees to be a surrogate mother for her brother and his wife.

I could do that, she thought at the time.

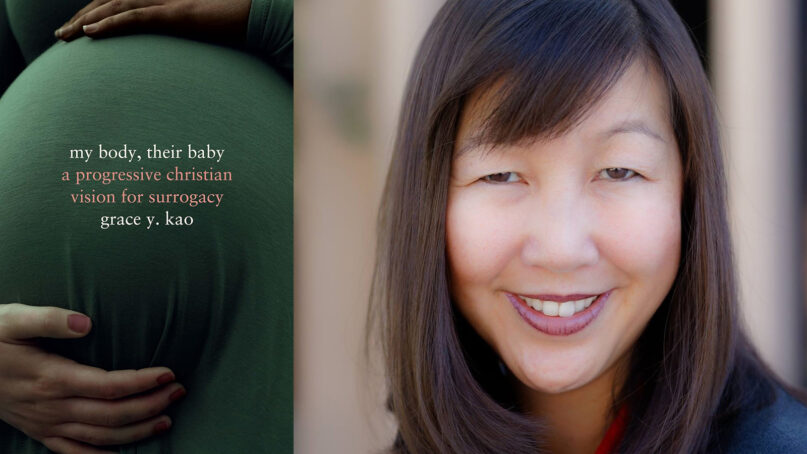

She was right. Kao would eventually become a surrogate for friends from a small group at her church, an experience she recounts in “My Body, Their Baby,” which was published recently by Stanford University Press. The book is both personal and philosophical — giving a firsthand account of surrogacy as well as detailing the legal, ethical and spiritual issues involved.

“I didn’t have my friend’s baby thinking I was going to get a book deal,” she said. “It was just a matter of people asking me questions and responding to them — and then friends saying, Grace, have you thought about writing about this?”

Kao, an ethicist and professor of Pacific and Asian American Theologies at Claremont School of Theology, said her decision to become a surrogate was pretty straightforward. Friends who had struggled with infertility needed help. While she didn’t love being pregnant — Kao and her husband had two children of their own before she became a surrogate — she didn’t mind it.

She volunteered to help.

Her offer to be a surrogate came up in 2015 while she and some friends were watching the Super Bowl. Most were parents in their 30s, who had waited to have kids while pursuing advanced degrees and careers. Several had experienced infertility.

Kao, who said she had an easy time getting pregnant, relayed a conversation she’d had with another friend who was considering surrogacy — and how, if that friend had asked her to be a surrogate, she would have.

Image by Diana Forsberg/Pixabay/Creative Commons

A friend at the party then asked the question: “Well, if you were willing to do it for her, would you do it for us.”

“I think she was even surprised at her own boldness,” Kao said. After more conversation and some tests, Kao agreed to carry her friends’ child.

The number of surrogates in the U.S. is growing, but it remains fairly uncommon. According to the latest available data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention — which tracks assisted reproduction technology, or ART, like in-vitro fertilization — about 1 in 20 (4.7%) embryo transfers involved a surrogate in 2020. That’s about double the percentage in 2011.

Still, there were only 7,786 attempts involving surrogates in 2020.

Kao said surrogacy is often viewed with suspicion — as some critics see it as exploiting women, while others question the ethics of the process. That’s especially true for religious groups like the Roman Catholic Church, whose teaching does not allow for ART, because it separates reproduction from sex.

Among Protestants, views vary, said Kao. She said evangelicals, though opposed to abortion, tend to be more accepting of in-vitro and other ART. Kao said her own tradition, the Presbyterian Church (USA), and other progressive Christians have mixed feelings about ART. While they’d support in-vitro fertilization, she said, they would be skeptical about surrogacy.

Also, many Christian groups tend to idealize adoptions. If her friends had adopted children, they would be seen as doing something valiant. When they chose surrogacy, they were viewed with more ambivalence. But Kao believes such concerns conflict with the progressive Christian support of same-sex couples, who can’t conceive biologically.

For Kao, both her desire to help her friends and her support of same-sex couples shaped her understanding of surrogacy.

“You’re not going to have that heterosexual vision of a man and a woman who love each other, come together and produce a child,” she said.

She said some mainline Christians, while they support same-sex couples, think that in-vitro fertilization should be limited to heterosexual couples. If same-sex couples want to be parents, then some progressive Christians think they should be limited to adoption — a position she is “deeply uncomfortable with.”

The decision to be a surrogate raised a host of questions — which Kao explores in the book. What would happen if testing revealed medical issues with the child she was carrying? Or if she had medical issues? What about if her friends, known as the intended parents, died before the child was born? And what would they tell the child — or family and friends — about the circumstances of their birth?

“I am a solid Christian in terms of believing the truth sets you free,” said Kao. But since she’s not the child’s parent, she doesn’t have the final say. While Kao is honest about her own experience, she is careful to respect her friends’ privacy. She let them see the book before it was published — and did not include her friends’ identities in the book.

She also addresses a question that often comes up in conversations about surrogacy. Was it hard to relinquish the child she had carried? Kao said no — because she knew from the beginning the child was not hers. But she did grow closer to her friends in the process.

That’s not uncommon, said Eloise Drane, founder of Family Inceptions, which works with surrogates and intended parents. Building a close tie between the surrogate and intended parent is an essential part of the process, she said — because so much trust is involved.

She also speaks from experience. Drane, a mom of five kids of her own, has been a surrogate three times. In each case, she became closer to the parents than the child.

“It’s not that I don’t love the child,” she said. “But the close-knit relationship for me was with the parents.”

Drane, who is Black, was raised Catholic and now identifies as a non-denominational Christian. Her faith plays an important role in her work, she says, not just in her words but through her actions. Her faith requires her to treat people with dignity and to make sure no one is taken advantage of in the surrogacy process.

“When you see this cross on my neck, you know that this for me is for real,” she said. “One of the things that God put me on this earth for is to help others.”

Drane said her investment in surrogacy comes from her own history. She donated a kidney to a cousin when she was younger, an experience that taught her we all have the ability to change the course of someone else’s life by our actions. That belief later led her to donate eggs and, then, to become a surrogate.

She said some Christians point to the Bible — especially the story of Abraham, Sarah and Hagar — to oppose surrogacy. In that story, Hagar becomes pregnant by Abraham as a surrogate for Sarah. Then after Sarah becomes pregnant herself, Hagar and the child are cast out.

But we live in a different world than the characters of the Bible, Drane argues. She also points to the story of Jesus — who was born without a human father.

Surrogacy, she said, is like any other human experience — it can be a blessing or it can be a curse. It all depends on the people involved and their ethics. Drane said she and her agency try to make it beautiful.

“Surrogacy can be enriching and a shared experience,” she said. “It doesn’t have to be transactional. I think people have lost the beauty of what surrogacy can be.”