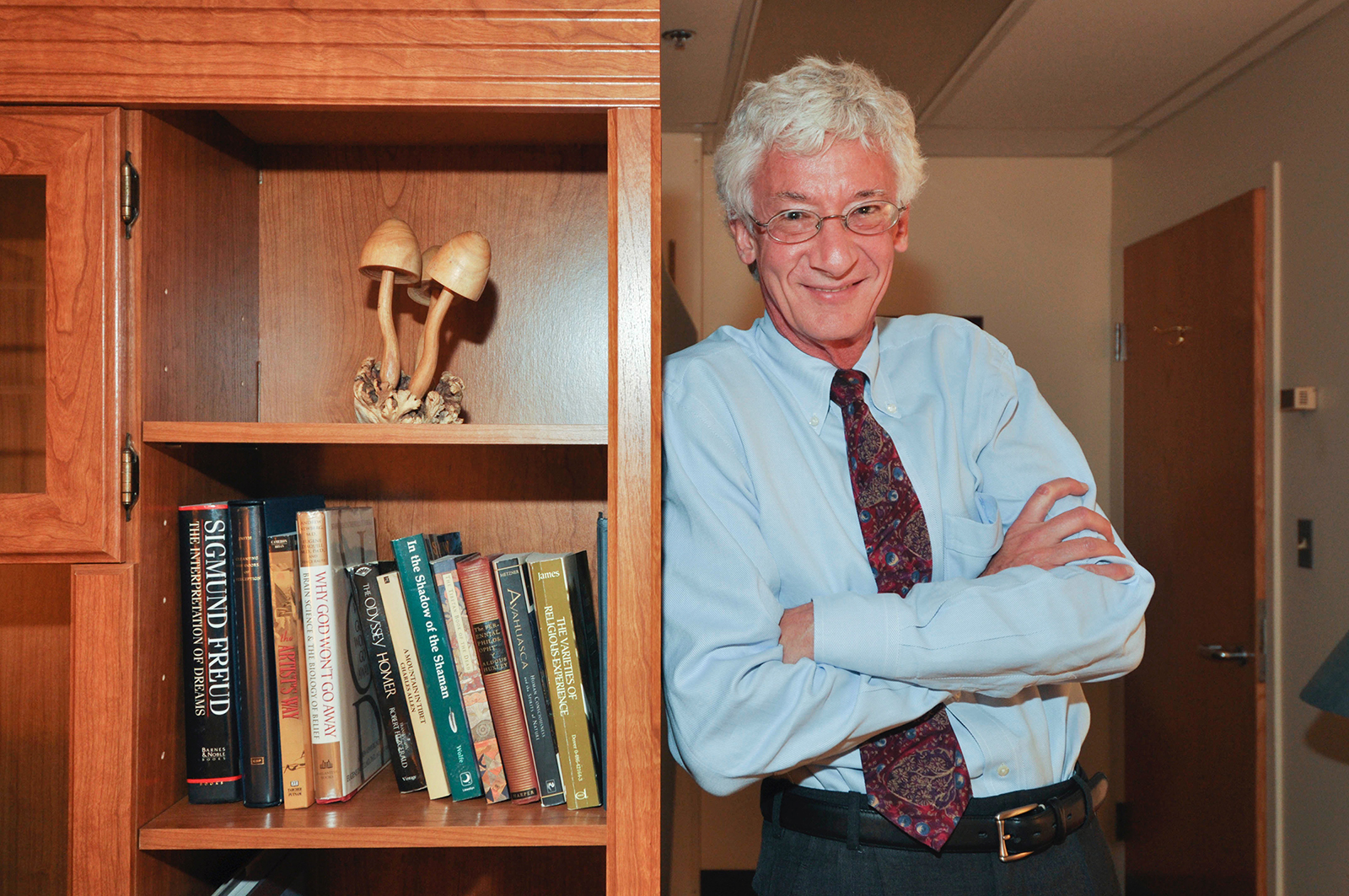

Roland Griffiths in an undated image. Courtesy photo

(RNS) — Last June in Denver, at a convention of the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies, Roland Griffiths stood onstage in the largest ballroom in the cavernous Colorado Convention Center. He was the star attraction at a sold-out dinner honoring him for his celebrated work as a scientist exploring the spiritual and psychological dimensions of the psychedelic experience.

Griffiths, the founding director of the Johns Hopkins Center for Psychedelic and Consciousness Research, looked on as a portrait of himself was unveiled by the visionary artist Alex Grey. Backlit by a glowing, yellow angelic aura, the image was reminiscent of a hagiographic icon in an Orthodox Christian church.

Honored, but also a bit embarrassed, Roland looked at the painting and shook his head. “That’s not me,” he said, going on to express his gratitude for the gift and acknowledging that he had become a symbol of something much greater than himself.

Less than four months later, on Oct. 16, Griffiths died at the age of 77 of the colon cancer he had been diagnosed with in November 2021.

Portrait of Roland Griffiths by artist Alex Grey. Photo by Don Lattin

Ironically, some of Griffiths’ best-known scientific work in recent years has been studying how psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy can help cancer patients deal with the depression and existential angst brought on by a life-threatening diagnosis.

Over the last year, in a video announcing his own diagnosis and in a series of media interviews, Griffiths left an inspiring testimony of how one man faces his own mortality. As the author of many obituaries over my four decades in journalism, I know to avoid words such as “struggle” or “battle” to describe Roland’s encounter with terminal cancer, but they wouldn’t apply anyway: “Adventure” seems a better descriptor.

Those of us who have experienced the ego dissolution that sometimes accompanies a high-dose psychedelic trip can testify that these altered states of consciousness can seem like a kind of dress rehearsal for death — sometimes terrifying, sometimes enlightening. Perhaps his study of these states allowed Roland to handle his actual death with such grace and equanimity.

I’ve had the pleasure of interviewing Roland at length over the last 15 years about his work at Johns Hopkins. Our last extended conversation was last year, for my latest book, “God on Psychedelics: Tripping Across the Rubble of Old-Time Religion.” Roland, a serious student of Buddhist meditation, had recently gotten his surprise cancer diagnosis. I asked him if he saw the hand of God in the psychedelic experience.

Not exactly, he said, at least not in conventional religious terms. “I’m interested in secularized spirituality,” Roland told me. “You can strip all the beliefs away and just get down to the basic fact that we find ourselves as these sentient creatures walking the Earth. We can touch and feel things. We can see things. We can speak and express complex ideas. And yet the only thing that we can ever really know is that we are aware that we are aware.”

We were discussing “God” because some questions had emerged around a much-anticipated and long-awaited study of how clergy respond to psychedelics.

Researchers at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore and NYU Langone Health in Manhattan administered psilocybin to two dozen healthy and “psychedelically naive” religious professionals — rabbis, priests, chaplains and seminary professors.

After careful screening and preparation, each was separately given two doses of synthesized psilocybin in a comfortable, supervised setting. The idea was to measure the chemically induced mystical experiences they might have had and follow up to see how that helped — or hindered — them in their ministry.

The study, which has been completed but not yet published nor publicly released, has already been criticized on the grounds that its participants may have been subtly and perhaps inadvertently encouraged to have a particular kind of mystical experience.

Expectations and suggestibility can affect how one responds to and interprets experiences on psychedelic drugs or sacred plant medicines. Over the last couple years, Roland and other scientists in the “psychedelic renaissance” have tried to separate themselves from those who see these compounds as the latest “miracle drug” — magical substances that will somehow inspire humanity to save us from ourselves.

But in that last conversation I had with Roland, he pushed back against the idea there was a theological or political agenda behind his Hopkins research. “We were not trying to turn people into evangelical psychedelic proponents,” he said.

“We are in a disconcerting psychedelic bubble right now in which people have unbridled enthusiasm for the potential of psychedelics to cure everything,” he told me. “Psychedelics are not harmless. People are going to die. People are going to become psychotic.”

Charles Grob, a psychedelic researcher who has worked with Roland for more than two decades, told me this week his colleague “has been pivotal in raising scientific standards and rigor in the field.”

Grob, a professor of psychiatry at the UCLA School of Medicine, said Griffiths’ work has proved that “mystical or powerful psycho-spiritual experiences can be reliably facilitated when psychedelic treatment is administered within the context of optimal conditions,” and that such experiences can be “a predictor of positive therapeutic outcomes.”

The portrait unveiled at the dinner honoring Roland last summer was embraced by a golden frame with words like “awe,” “unity,” “ecstasy,” “paradox,” “holy,” “ineffable spirit” and “ultimate reality.” These words were taken from questions for participants in the religious professionals study designed to determine if they had a “mystical experience.”

The philanthropist T. Cody Swift, who has both worked with Griffiths and helped fund his research, remembers his friend’s reaction to the saintly portrait presented at the MAPS convention. He recalls Roland saying how he’d like to “knock the painting off its pedestal.”

“I loved his response because it reflected his humility and his vigilance around our tendencies of projection,” said Swift, founder of the RiverStyx Foundation. “I suspect he did not want any ego inflation to get in the way of his work.

“Roland brought science and spirituality together,” Swift added. “He always strove to manage expectations around the promises of these studies, always cautioning against overenthusiasm and overconfidence. I remember him often saying, ‘Let’s see,’ meaning, ‘Let’s see what the data or experience shows.’”

But Roland also recognized that there is something all humans experience that the data does not answer. “What is this project of life about?” he asked in our last conversation. “We don’t know the answer to that. No one does. Science doesn’t answer that. It’s the human condition. We are born into this mystery. Many of us get wrapped up in narratives about our lives that distract us from the mystery. But there is something about these experiences, from the way I see them, that speaks to that deepest mystery.”

(Don Lattin, a former religion writer at the San Francisco Chronicle, is the author of several books about the modern psychedelic movement, including “The Harvard Psychedelic Club” and “Changing Our Minds.” The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)