(RNS) — In the middle of old Berlin, Christians, Muslims and Jews have been creating an interfaith center with a church, mosque and synagogue all in the same building. Since breaking ground on the House of One, meant to celebrate the three monotheistic religions, the groups behind the project have been looking forward to its opening in 2028.

They didn’t reckon with Oct. 7. The Israel-Hamas war, which began a month ago with Hamas’ surprise butchering of Israelis and the ferocious Israeli response, has spread Middle Eastern tensions throughout Europe. Germany has been no exception.

On Oct. 10, the partners behind House of One met for a prayer meeting at the building’s construction site. Imam Kadir Sanci of the Forum for Intercultural Dialogue, one of the organizations involved in the effort, acknowledged that words seemed a strange weapon against war. But, he said, “it had an effect: Many more people listened to us, many more are ready to walk this path with us.”

But they have had stiff competition in the opposite direction.

About a week after the prayer meeting, unknown persons threw Molotov cocktails against a nearby Berlin synagogue. Police on special guard duty were able to put out the flames before the building caught fire.

Soon after that, police reported that officers had been posted at 150 Jewish addresses around Berlin — synagogues, schools, community centers, shops and others — to prevent further attacks.

A series of smaller demonstrations followed, some calling for an end to war, others defending Israel. Several pro-Palestinian rallies were banned because police considered them antisemitic.

On Oct. 22, German President Frank-Walter Steinmeier addressed a pro-Israel rally of at least 10,000 at the Brandenburg Gate. “Protecting Jewish lives is our civic duty,” he said. “Every single attack on Jews and Jewish institutions is a disgrace for Germany.”

But stop-the-war marches continued around Germany, many with Palestinian flags. Last weekend, protests in Berlin drew at least 8,500 demonstrators, from Jewish pacifists to Islamist and far-right antisemites. Some shouted slogans like “freedom for Palestine” and accused Israel of “genocide” and “apartheid.”

Protesters hold posters and flags during a pro-Palestinian rally in Berlin, Oct. 28, 2023. (AP Photo/Markus Schreiber)

The largest crowd appeared in the western city of Düsseldorf, where some of the 17,000 protesters — a turnout far bigger than expected — carried signs that questioned or minimized the scope of the Holocaust, prompting police to confiscate them. Another 3,000 marched in Essen, with some calling for a caliphate — or Islamic rule — in Germany.

As the crowds have grown, German authorities, like their counterparts in France and Austria, have banned some pro-Palestinian protests, worried that they could provoke violence. But German leaders also appear to be caught between their historical support for Israel — an anchor of post-World War II German policy — and the popular response to the crisis.

Even Vice Chancellor and Economics Minister Robert Habeck, whose Green Party used to hew a pacifist line, delivered an impassioned appeal on Nov. 1 for Israel, against Hamas and against anyone on the left or right who relativized this position.

The crisis has also exposed cracks among Germany’s Muslim communities, which have expanded significantly since 2015, when the country took in about a million Middle Eastern refugees, mostly fleeing the Syrian civil war. These newcomers tend to be more attuned to disputes with Israel than Germany’s older Turkish-based Muslim minority.

In late October, Seyran Ates, the female imam of Berlin’s progressive Ibn Rushd-Goethe Mosque, who declared solidarity with Israel after the initial Hamas attack, said the immigrant influx of 2015 had “a certain social class that brought antisemitism with it.” The mosque later announced it would close for at least a year in the face of threats from the Islamic State group.

An artistic rendering of the House of One design in Berlin. (Design by Kuehn Malvezzi, photo by Ulruich Schwarz, courtesy of House of One)

Even the interfaith leaders of House of One had difficulty finding the right words. A Catholic member had to apologize to Jews for using the word “Palestine” in inviting members to a prayer meeting.

Christian groups behind an interfaith declaration in Munich annoyed local Muslims by insisting they first denounce the Hamas massacre, something the Muslims said they had already done.

Complicating attempts to respond to the drama playing out in the Holy Land is the antisemitic stain on Germany’s history. Inconveniently, the conflict and protests are taking place as multiple Nazi-era anniversaries are coming around: On Nov. 9, 1923, Adolf Hitler staged his failed Beer Hall Putsch against the fledgling German republic. On the same day in 1938, the Nazi pogroms of the Kristallnacht started.

The religious leaders behind the House of One, as they vow to keep the project on course, have preferred to remember a more optimistic of these anniversaries: the fall of the Berlin Wall on Nov. 9, 1989.

“The border between East and West in Europe was not brought down in 1989 through violence, but with candles in hand and hymns from the church,” said Rabbi Andreas Nachama on German radio recently, recalling the many “peace prayers” in Protestant churches back then. “We believe we can bring about peace through prayer,” he said.

- Imam Kadir Sanci. (Photo courtesy of House of One)

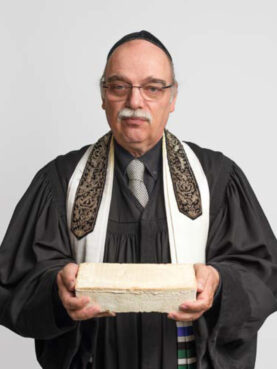

- Rabbi Andreas Nachama. (Photo courtesy of House of One)

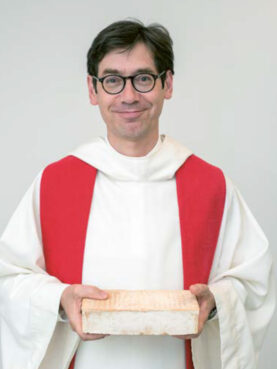

- Pastor Gregor Hohberg. (Photo courtesy of House of One)

Meanwhile, Protestant Pastor Gregor Hohberg, head of the House of One foundation, announced that the next interfaith prayer meeting will be held in his nearby Church of St. Mary on Sunday (Nov. 12).

“We invite everyone,” he wrote in the invitation. “The perplexed, the despairing, those who seek consolation, Israelis and Palestinians, teachers and students, seculars and believers of all faiths — let us listen together, pray, sing and thus visibly strengthen ourselves for peace and humanity.”