(RNS) — I arrived by U-Haul at the Marathon Jewish Community Center from my home in Upper Manhattan, a white-knuckle journey from the U-Haul location in Spanish Harlem and over the RFK bridge to suburban Douglaston, Queens. For months, I had put off this trip to pick up my father’s bimah chair — a seat of honor for a synagogue’s rabbi on the bimah, the podium of the synagogue’s sanctuary.

For months I had ignored friendly emails reminding me that the sale of the building had gone through, and please would I come by before everything that was unclaimed would go out to the curb for garbage pickup.

On a recent Wednesday night, just before midnight, I finally reserved the U-Haul. Why did I delay so? Over the past several years, I had been to the synagogue more than half a dozen times, even helping to plan a farewell ceremony after I learned that the community was merging with another and a sale of the building was being considered.

My father, Henry Israel Dicker, served as spiritual leader of the Marathon Jewish Community Center from 1955 until 1977. For most of my father’s tenure as rabbi of this close-knit, active and liberal Jewish community, four bimah chairs — perfect clones — accommodated him and other honored occupants on Shabbat and the Jewish holidays. Situated on either side of the Torah Ark, the chairs were typically reserved for the rabbi, cantor, gabai (sexton) and synagogue president.

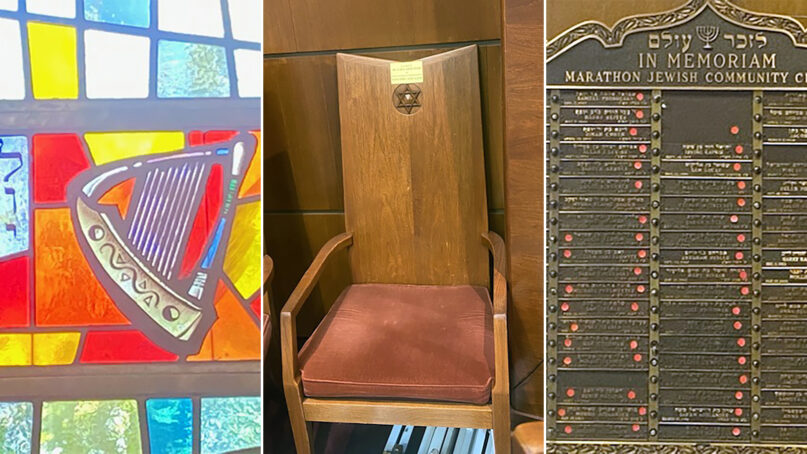

The Dicker bimah chair at Marathon Jewish Community Center in Douglaston, Queens, New York. (Photo courtesy of Shira Dicker)

On the occasion of a bar or bat mitzvah, the lucky boy or girl got to sit in a bimah chair, usually next to the rabbi.

I have no idea when they were commissioned, but the bimah chairs were present at my baby naming, in April of 1961, when I was adopted by my parents at the age of 5 months. As I grew up, a doted-upon First Daughter of the community, I was even then conscious of a certain hilarious dissonance in being a rabbi’s daughter in the raucous 1970s.

The truth is, being a Jewish kid in the latter half of 20th-century New York was a dream, a visit to Disneyland, an absolute holiday from the kind of caustic hostility we are seeing now. Being Jewish seemed an inextricable element of the life of the city. For the Salute to Israel parade each spring, we marched up Fifth Avenue in blue and white costumes, performing well-rehearsed choreography to enthusiastic applause from bystanders. On Simchat Torah, we danced in the streets with Torah scrolls without a moment’s fear, much less police protection.

It is no exaggeration to say I never experienced a millisecond of concern, never checked to see if my Chai necklace was visible or if I might be targeted for my Israeli appearance or Hebrew name.

The day I retrieved the bimah chair — two weeks after my 63rd birthday, three years after my father’s death — was the day that the Marathon Jewish Community Center ceased to exist. After the chair was deposited inside the U-Haul with the help of a kind worker and a weeping office manager, I returned to peek inside the sanctuary still adorned with jewel-toned stained glass windows featuring the 12 tribes of Israel.

Detail of the tribe of Levi, the musicians, from the stained glass windows at the Marathon Jewish Community Center in Douglaston, Queens, New York. (Photo courtesy of Shira Dicker)

Gone were the rows of wooden pews. Gone were the wall hangings with memorial plaques. Gone was the majestic Hebrew lettering on the back of the bimah. Gone was the eternal light and the Torah Ark.

And gone were the bimah chairs.

My old shul. My childhood and adolescence. My head filled with the cacophony of the multitude of prayers that were intoned within these walls. All the days of THEN swept over me in watercolor brush strokes: days of awe, of mourning, of celebration. A Jewish community once lived here. It was mine. it is gone.

I drove the U-Haul back to Manhattan in a state of frozen grief. My dad, who had a thriving career as a clinical psychologist after he left Marathon and the rabbinate, would have told me that my procrastination about fetching his chair was rooted in denial of the finality of his death. Bringing his bimah chair to my home made the closure of the beloved building, a place I still inhabit in my dreams, a reality.

My father’s bimah chair now sits at the head of my dining room table, its handsome wooden back angled ever so slightly, an engraved Star of David its only adornment. If I knew anything about trees I might be able to say what kind of wood it is made from, but I can only report that the wood is warm and caramel colored. With its faded velvet cushion, the chair conveys the essence of a throne, only slimmer and more elegant.

However streamlined its beauty, it is a man’s chair nonetheless. It was designed in an era that could not foresee the possibility of female clergy.

Members of the Marathon Jewish Community Center march in the Salute to Israel Parade, May 6, 2007, in New York. (Photo courtesy of Joseph Levine, NEQJCC)

My oldest son, Adam, visiting from Europe, was able to help me schlep the chair into the apartment. The last time he had seen his grandfather was in the fall of 2019 at the beginning of what was to be his last year of life. My father died on the last day of October 2020 when the pandemic was raging and Adam was unable to fly home for the funeral.

Carrying his grandfather’s bimah chair across the threshold of his childhood home, I imagined my son holding my father aloft as my father had held him when he was a tiny infant at his bris nearly 40 years ago. My husband gently placed the chair at the head of the dining room table.

I imagined my father sitting in his bimah chair, transformed into the Chair of Elijah, the seat of honor at a circumcision. I felt surrounded by the aching memory of his warm presence and then I let him go, knowing that it was a mercy that my father left the world when he did, ascending to heaven in the manner of Elijah, chariot-borne.

(Shira Dicker is a writer and publicist whose short story collection, “Lolita at Leonard’s of Great Neck and Other Stories From the Before Times,” will be published in May 2024 by Wicked Son. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)